In my head, John Schlesinger’s 1969 classic Midnight Cowboy is intertwined with Miloš Forman’s 1979 adaptation of Hair for some reason, to such an extent that I tend to mix up Jon Voight and John Savage. I have no convincing explanation why this is the case, but I suspect it may be that I watched at least the beginning of Midnight Cowboy at an age when I was too young to really take in what the film was about, so all that stuck with me was a young hick from one of the more rural states taking a bus ride to New York to begin a new life and, once there, falling in with a very different crowd than what he was previously used to. Perhaps Harry Nilsson’s melancholy hit “Everybody’s Talkin'”, playing over the Greyhound ride Joe Buck (played by Voight) takes to the Big Apple, added to that mostly inaccurate memory.

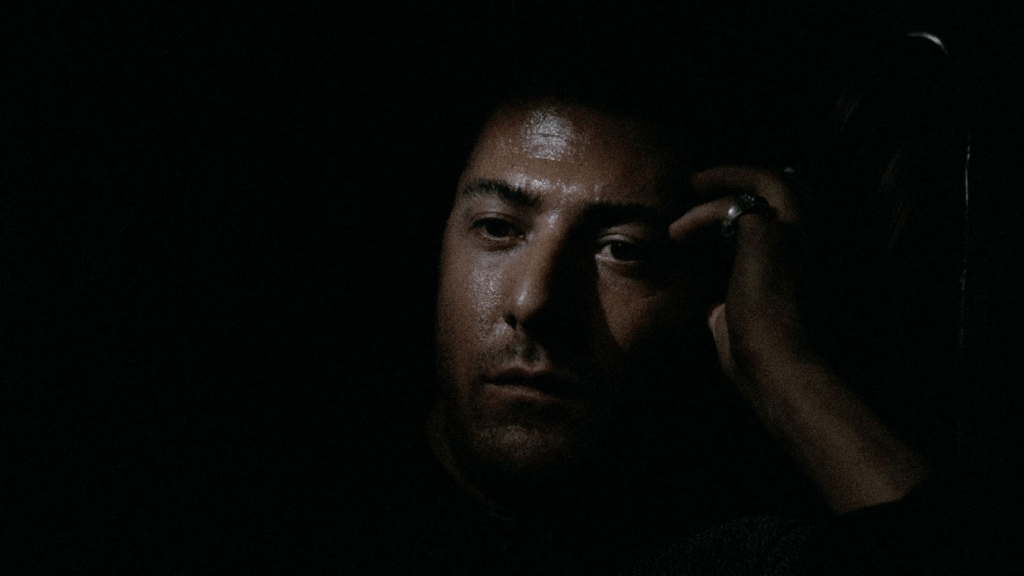

Those similarities are there, but they’re entirely superficial. Where Hair‘s Claude Hooper Bukowski goes to New York City after being drafted into the Army to go to Vietnam, Joe Buck has drafted himself into a very different kind of service: he wants to put his carnal talents, and his cowboy outfit, to good use to make the women and men of New York happy. And there’s no idealised, singing hippie tribe waiting to take Joe under their wings, but a fidgety, coughing con man named Rico “Ratso” Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), who at first is eager to trick the naive Texas hick out of twenty dollars – but then, for a while, becomes the midnight cowboy’s only friend and companion.

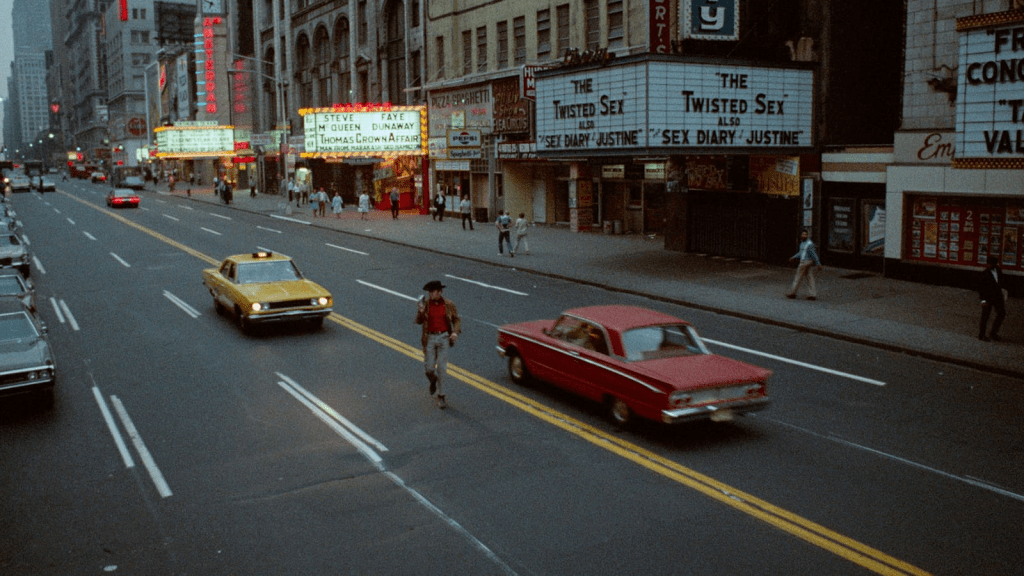

Schlesinger’s New York is a nightmarish place. Its denizens are crooks, crazies, sad and lost souls, trying to keep their heads above water, if just barely. Joe Buck, something of an innocent in spite of his career ambitions in the world’s oldest profession, is no match for them: the first trick he tries to turn, a middle-aged woman that has seen better days herself, ends up getting him to pay her after they’ve had sex. Next, he falls for Rizzo’s con, and the man he’s sent to see turns out not to be a pimp but an unhinged religious zealot. Everyone in Joe’s path seems out to get him in one way or another. This Big Apple is rotten to its core. It is a place that will chew you up and spit you out.

More than that, though, Midnight Cowboy‘s New York is a deeply lonely place, in particular for outsiders such as Joe Buck – and, as it turns out, Rizzo, who attempts to mollify Joe for conning him by offering to share his squat. Rizzo is still trying to get something from Joe, who has quickly learnt not to trust the man, but what both of them really want, perhaps more than they understand themselves, is companionship.

Is Midnight Cowboy a gay film? Are Joe Buck and “Ratso” Rizzo homosexuals, perhaps barely aware of their desire for one another? There are hints throughout the film that this may be the case, but these are often ambiguous. As a hustler, Joe seems to be open to offering sex to men as much as to women, but this may be a professional thing only, and the few times when we see him with male partners he becomes violent – which needn’t mean anything, of course, as this could be internalised homophobia on his part. When it comes to Rizzo, it’s more difficult because the character never seems to be looking for sex at all, and the more ill he becomes as the film progresses, the less likely it is that anyone would want to become intimate with him. Rizzo is also the most vocally homophobic character in the film, constantly needing to make it clear that he’s not queer, no way, no siree… and it is this habit that makes it difficult not to think that Ratso doth protest too much. Then there is that markedly camp fantasy of Rizzo’s later in the film, where he imagines the life he and Joe could have in Florida – and, obviously, the life Joe and Rizzo have in the derelict apartment they’re squatting is notably domestic, although it is a desperate caricature of domesticity in abject poverty.

But while the question of whether these characters are queer is relevant when it comes to representation, it may be less central thematically. Rizzo and Joe are desperately lonely and longing for companionship, and the question of whether either also desires the other is not immaterial but it is secondary. Gender roles may be more relevant than sexual orientation: Rizzo’s insistence that he isn’t gay finally has more to do with what needs he believes he can and cannot express as a man, and he finds it easier, at least at first, to con Joe out of twenty bucks than to ask him to stay and keep him company. Rizzo’s potential homosexuality would contribute to his being a lonely outsider starving for friendship, but we see a handful of other characters in the film who are out of the closet, and some of these seem comfortable with themselves in late ’60s NYC. In the end, I suspect it is less the closet that Rizzo is locked up in than it is his insecurity and fear of rejection. If we need to attribute his need for Joe’s company to his sexual orientation, to some extent this is the kind of thinking that has made the character what he is: a man who is barely able to express longing and loneliness, who needs to cover his need for the comfort of others under an unconvincing veneer of glib cynicism.

Verdict: Regardless of whether either of the two main characters, Joe Buck and Rico “Ratso” Rizzo, is homosexual, and whether their need for each other’s company is sexual in nature, Voight’s Joe and Hoffman’s Rizzo are one of the most touching, memorable male pairs in American cinema. Schlesinger’s film is unmistakably a product of the late 1960s, from its costumes and camera angles to its soundtrack and the inescapable “Everybody’s Talkin'”, and it strikes me as dated in its depiction, through Joe’s eyes, of New York as a reactionary caricature: the Big Apple as a present-day Sodom of sex and drugs and mental illness. But his portrait of these two outsiders has a tender sadness that was rare at the time in Hollywood and that is still rare. It is this tenderness in Schlesinger’s depiction of two lost and lonely souls that makes Midnight Cowboy an enduring classic.

One thought on “Criterion Corner: Midnight Cowboy (#925)”