In her fascinating series “Erotic ’90s”, Karina Longworth, creator and host of the long-running podcast You Must Remember This, discusses Thelma & Louise, Ridley Scott’s early ’90s pop-feminist modern classic. (Should I leave out that “modern” once a film is over 30 years old?) I remember being faintly aware of the cultural conversation about Scott’s film at the time, but as a teenager in the pre-internet age I certainly didn’t get more than the occasional snippet. At school, our English teacher had a subscription to Newsweek, so I may have read an article about the film, but other than I wouldn’t have been known about the brouhaha in the US that Thelma & Louise prompted. Listening to Longworth’s podcast, it’s crazy to imagine the culture wars hysterics that gripped especially male critics – but then, in 2023, no amount of culture war craziness should come as much of a surprise.

I liked Thelma & Louise a lot when, about a year after its release, it was shown on the English-language movie channel we were able to watch with our satellite dish and receiver, but I don’t think I’ve seen it in over 20 years. When Criterion announced that they were planning a 4K release, I thought that this was the perfect opportunity to revisit Scott’s film. At the same time, I was somewhat wary: in terms of feminism, the world is largely a very different one than it was in 1991. I’m different too: not that I was a little reactionary troll in my late teens (I hope), but something would be wrong if I still had the exact same thoughts about gender relations as I did back then. Would Thelma & Louise hold up, or would it be a faintly embarrassing time capsule of outdated views?

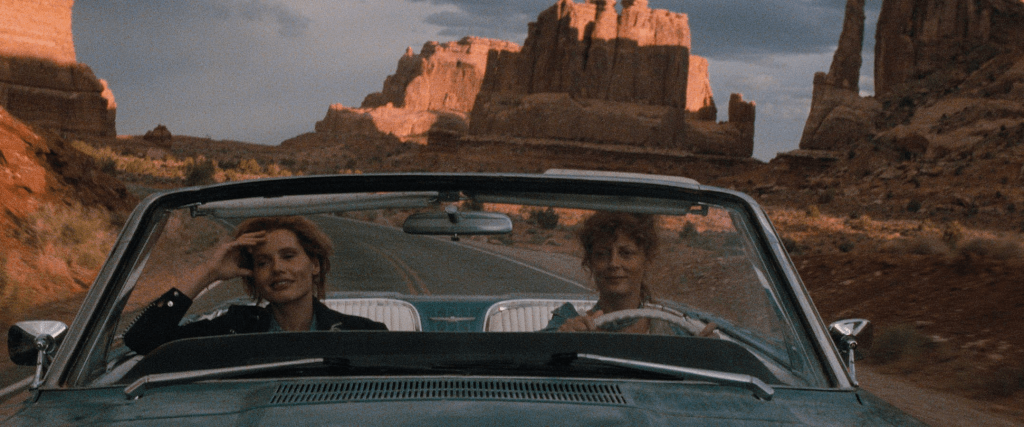

Honestly, even if the film felt dated, this would still be a wonderful release, even just visually. Criterion once again proves that it’s got some of the best-looking 4K releases on the market. Thelma & Louise was filmed by English cinematographer Adrian Biddle, who’d worked on films with very effective cinematography (such as Aliens, Cameron’s sequel to another Ridley Scott classic), but to my mind nothing stands out as much as his work on Thelma & Louise, and the Criterion release brings this out fantastically. The film looks gorgeous, in its saturated daytime scenes as much as in its nighttime sequences, with car lights and neon signs reflected in windscreens and rain-soaked roads. The interiors pop, but it’s especially the exterior scenes that shine, showing the landscapes of a quasi-mythical America to such good effect that I had to physically stop myself from booking a flight and a transcontinental road trip right there and then.

But it’s rare that Scott doesn’t make a good-looking film, even if Thelma & Louise looks better in this release than it ever has. What about the rest of it? Thelma & Louise is a product of its time – but it’s striking how relevant that time still is when it comes to gender politics, perhaps even more so in 2023 than ten or twenty years ago. What shows the film to be a product of the ’90s most of all is that it’s about two white women in a predominantly white America; in the 2020s you wouldn’t get away without at least some acknowledgement of intersectionality or more of an understanding of systemic discrimination. But that’s not the kind of film Scott makes anyway: he is at his best when he is at his most instinctive, and his instincts as a filmmaker are at the top of their game in Thelma & Louise. This is not an intellectual proto-#metoo treatise, it’s an experiential, from-the-gut road movie about two women who, after years of being pushed around by men, push back. Just like Louise’s reaction to Harlan’s obscene fuck-you, the film is a reflex reaction to being treated like shit and hitting back.

I do wonder if, in 2023, this story would have the edges of the version we have. One of the things I still like best about the film, and about Khouri’s script, is this: after Harlan nearly rapes Thelma (Geena Davis) and Louise (Susan Sarandon) stops him by pointing her gun at him, they’re safe and walking away, when Harlan hurls his final jibe at them – and Louise shoots him. It is murder, there’s no doubt about that. The film doesn’t soften the moment or make Louise’s actions more justified by making it unmistakably about self-defense. And the film runs with this. Its premise is: Men are lucky that this doesn’t happen sooner and more often. Louise is a criminal, and Khouri and Scott pretty much go: either you understand why this happened, why Louise pulled that trigger, you relate, or this film isn’t for you. There’s a radicalness to it that isn’t spelled out in dialogue, but it gives Thelma & Louise teeth.

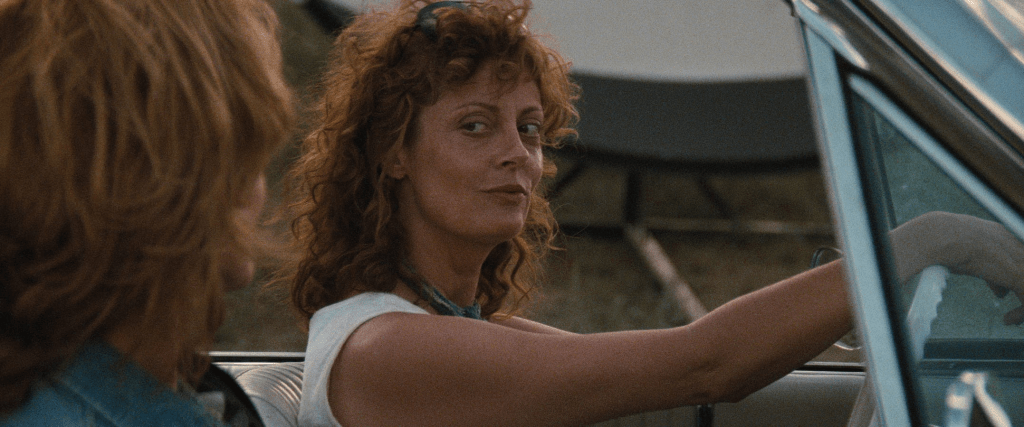

The film is also another instance of Ridley Scott working with a perfect cast. The side characters work well, from Christopher McDonald’s pathetic bully of a husband to Brad Pitt’s kid outlaw, even if some are little more than jokes – but it’s Sarandon and Davis that shine. They remain an iconic pair of American cinema, as memorable as Robert Redford and Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (whose ending prefigures that final flight into the Grand Canyon). It’s easy at first to underestimate Davis, whose role goes more for the humour in Khouri’s script, in spite of the almost-rape that sets the plot in motion, but Thelma’s growth is captured beautifully in her performance, and Sarandon brings a weary sadness and a wealth of emotions kept on the inside to the part. Each is great on their own and they’re perfect in combination.

Verdict: Don’t come to Thelma & Louise expecting an intellectual, well-reasoned treatise on the complexity of feminist struggles in modern America. It doesn’t have anything much to say about systemic discrimination, and it definitely doesn’t know about intersectionality. But that’s not what Thelma & Louise sets out to be. The film’s perspective is limited by design: this is a film about two women who have had enough, who lash out against a world that grinds them down, day after day after day, and it’s the movie’s anger and what beauty and grace it finds in comradeship between its titular characters that still shine, more than thirty years after its release.

Even with all its anger, Thelma & Louise is fun and exciting in effective (if somewhat populist) ways, but where Thelma & Louise shines most for me is in a visual poetry that reclaims the quasi-mythical American West and its iconography for a pair of women outlaws. It would have been easy for Scott’s film to simply come across as a pop-feminist appropriation of the Marlboro aesthetic, but Thelma & Louise offers more. There is a dreamlike shimmer to some scenes (never captured more beautifully than in this re-release), a vibe that is beautiful and melancholy, that I cannot describe as anything other than darkly, fatalistically transcendent, where Thelma and Louise as much as the audience sense that the real world only has space for these two women if they defer to its demands for them to stay in their small, clearly defined boxes. A life under these circumstances would be suffocating, and the freedom that breaking out of the confines affords them is palpable – as is the sense that it cannot last.

One thought on “Criterion Corner: Thelma & Louise (#1180)”