Apart from the ’70s anime version of Heidi (which I, like so many kids growing up in Switzerland in the 1980s, watched much more of than any more ‘native’ versions of the story), for which Hayao Miyazaki worked on scene design, layout and screenplay, my first proper encounter with the director and his work that I was aware of was Princess Mononoke (1997). Japanese animation didn’t often make it into Swiss cinemas at the time, at least other than the occasional showing of a classic of the form such as Akira or Ghost in the Shell, so I had to travel to another city to catch the film at the cinema.

It was absolutely worth the journey: seeing Princess Mononoke was a breathtaking experience. The film felt archaic and epic and strange, though at the same time intimate and very personal. It grappled with big moral questions, but without reducing these to good vs evil simplicity. (Ian Danskin’s video essay “Lady Eboshi is Wrong” on the topic is well worth watching.) Even just on an aesthetic level, Princess Mononoke was visually stunning, and its score, easily one of Joe Hisaishi’s best, complemented the visuals perfectly. Miyazaki’s films deserve to be seen on a big screen – and yet, since seeing Princess Mononoke at a cinema, I only managed to do the same with Spirited Away. All of Miyazaki’s other films (and everything that Isao Takahata did) I only ever saw on my TV.

So, when Miyazaki announced (not for the first time, mind you) that his latest production for Studio Ghibli would be his final film, I wanted to make sure that I’d see it on a big screen. The cinema at which I managed to see The Boy and the Heron wasn’t exactly a big one, but it still made a difference to be sitting in the dark, in a comfortable seat, and to look up in the dark at that lit rectangle, waiting for Miyazaki to do his magic.

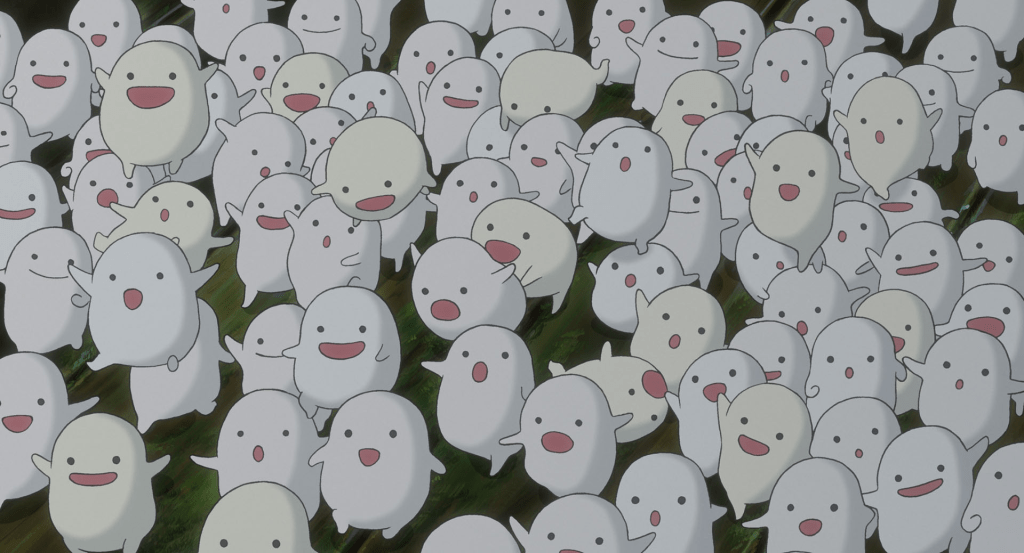

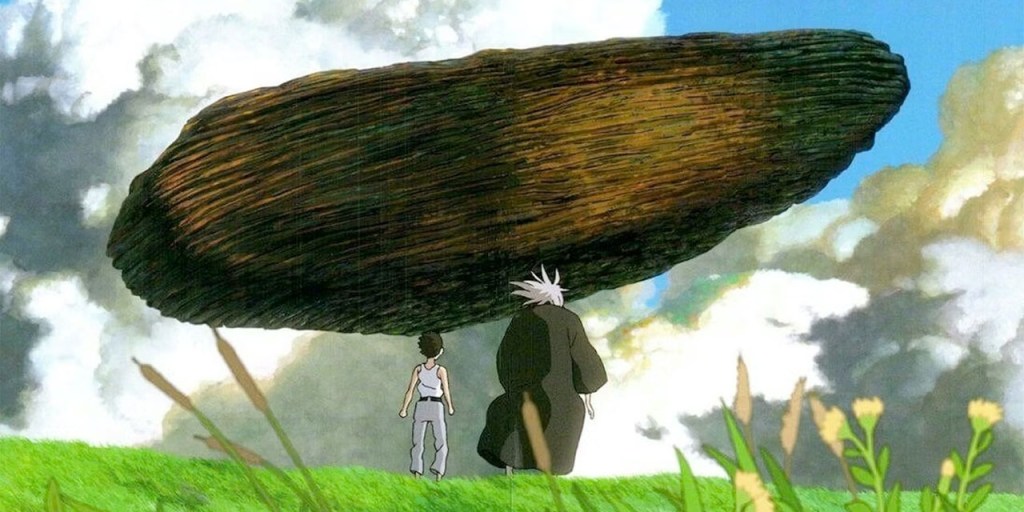

In brief: it was worth it. Visually, The Boy and the Heron is up there with his best films: once again, it is epic and sweeping, but the sights it offers go beyond grand spectacle. There is a strangeness to the images, even something offputting when the story calls for it: at times, the organic shapes that Miyazaki depicts on screen can almost veer into body horror, as all sorts of beings move and ripple and change in beautiful and disturbing ways. And, as always, Miyazaki’s epics never lose sight of the individuals that the stories are about, and that intimacy is perhaps what makes his films most memorable. He manages to reconcile these seeming contradictions into stories that create whole worlds and then puts the focus firmly on the individuals in these worlds, and he excels both at frantic action and at calm and poetic repose. And, once again, Miyazaki’s frequent collaborator Joe Hisaishi has written a soundtrack that reflects both the epic and the intimate in the director’s stories and his worlds. Hisaishi’s score complements the emotions with which the film works without ever coming across as manipulative or sentimental (though Hisaishi has used sentiment to great effect in the past).

If The Boy and the Heron remains Miyazaki’s final film and I never will see a new Miyazaki on the cinema screen, I will be content. But differently from many of Miyazaki’s other films, and definitely differently from both Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, I feel myself somewhat torn on this one, perhaps more so than with any of the other films. Because as I left the cinema, my heart and my head had very different reactions to the film I had seen. The film had evoked strong feelings in me, but it also left me confused. This isn’t altogether rare with films from countries and cultures I’m not all that familiar with: I find it difficult to say whether I don’t understand because the storytelling is unclear or because I’m missing some key context. Am I not getting a certain character or a story development because I am unaware of certain cultural implications or storytelling conventions? In an English-language film, I’m more willing to say that a certain plot point doesn’t work for me, even that it’s not well done, because I feel I have more of a grasp of the underlying sign system. The problem is this: how can I tell the difference? I remember Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle: the film is a very loose adaptation of Diana Wynne Jones’ novel to begin with, but some of the changes to the plot didn’t make much sense to me, feeling like Miyazaki was superimposing frequent thematic concerns of his onto material that wasn’t really made for them. When I later discussed this with a friend who’d lived in Japan for a while, he argued quite convincingly that I was missing elements that would be much more obvious to a Japanese audience, and that knowing these would have resulted in Miyazaki’s choices making more sense to me.

It was such questions that went through my head as I was watching The Boy and the Heron. Miyazaki’s films are generally very approachable, even those that depict the Japan of history, legend or folklore. Certainly, there are elements that are strange and that benefit from a bit of supplementary reading, such as the animal gods of Princess Mononoke, or Spirited Away‘s No-Face, or even the cultural and historical background of The Wind Rises. But with all of these films I felt when I first watched them that I understood them: I understood the characters’ motivations and the underlying themes.

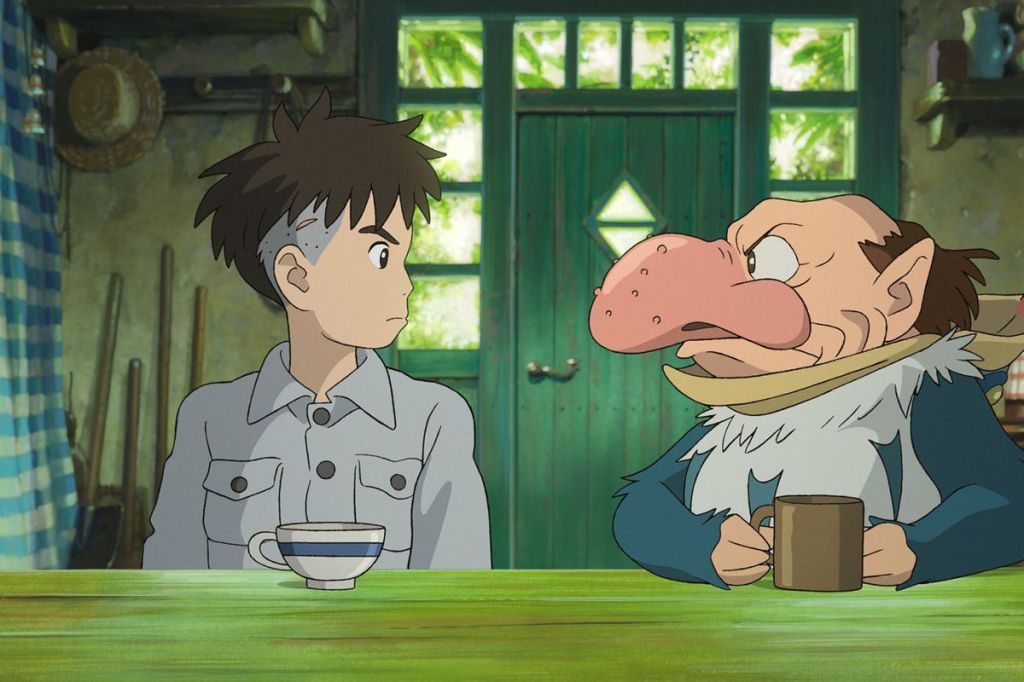

The Boy and the Heron‘s story starts off clear enough: 12-year-old Mahito loses his mother in the 1943 firebombing of Tokyo. A year later, his father Shoichi is set to marry Mahito’s aunt, the sister of his late mother, and she is already pregnant. They move to her estate in the countryside, near to the munitions factors Shoichi owns. There, a strange grey heron taunts the boy and leads him to a derelict tower that is revealed to be the entrance to a fantastic realm. There are echoes, both aesthetic and thematic, of several of earlier Studio Ghibli films, both by Miyazaki and by others: Spirited Away, The Wind Rises, even Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies. The Boy and the Heron‘s closest sibling is certainly Spirited Away, in which a young girl finds herself in a strange land, trying to navigate its strange rules and customs in order to save her parents, which is reflected in Mahito trying to find and rescue his aunt who has withdrawn to the magical world on the other side of the tower. But while both Spirited Away and The Boy and the Heron are coming-of-age tales, there is something grimmer and more pained both to the grieving Mahito and to the world he enters.

One key difference between the fantastic realms of the two films is that Spirited Away‘s world of spirits seems to have an existence of its own, and Chihiro enters it as a visitor, albeit one on a mission. Meanwhile, the history of Mahito’s family, further back even than his mother, is intertwined with the fate of the world he finds – and at the same time, this world reflects his loss, his fears, and his particular need to move past the trauma he has experienced. The fantastic realm is both more overtly symbolic than that of Spirited Away and more heavily plotted around the child protagonist finding themselves a stranger in a strange land, and the result is a Miyazaki film whose plot may just be more clunky and cumbersome than any of his other films. Individual sequences are often evocative, even moving, but more than with Spirited Away, I was left with the sense that the images and scenes were supposed to mean something specific for Mahito, his sense of self and his development as a character. It is easier for the audience to identify with Chihiro, even if she’s a young Japanese girl, because the world she finds herself in is as strange and wondrous to her as it is to us. The significance of the world Mahito ends up in to the boy himself remained opaque to me much of the time.

Though while The Boy and the Heron‘s plot left me somewhat confused, with me getting the broad strokes but feeling increasingly lost with many of the details, the world he once again creates on screen cannot be faulted – or indeed the worlds. His fantastic realms have the heft and tactility of his real worlds. There are few filmmakers, whether they work in animation or in live action, that can make you smell and taste and feel the grass and leaves. His more outlandish character designs remain striking, yet even at their most grotesque it is clear that there is affection for these characters and creatures. And before the plot becomes more complicated, it is once again wonderful just to breathe in Miyazaki’s wonderful worlds. More than that, before the film’s plot started getting in my way, I felt that I understood the underlying emotions the film was vibrating with: Mahito’s sense of loss, his resentment of his aunt and his father, his trying to find a place for himself while struggling to let go of his traumatic past. The Boy and the Heron is more harrowing and suffused with a deeper sadness than many of Miyazaki’s other films. Before the plot kicks into higher gear, much of the film struck me as an extended variation of Spirited Away‘s beautiful, heartbreaking train journey – a sequence that is all the more effective for working entirely on the vibes of the scene than on anything that actually happens.

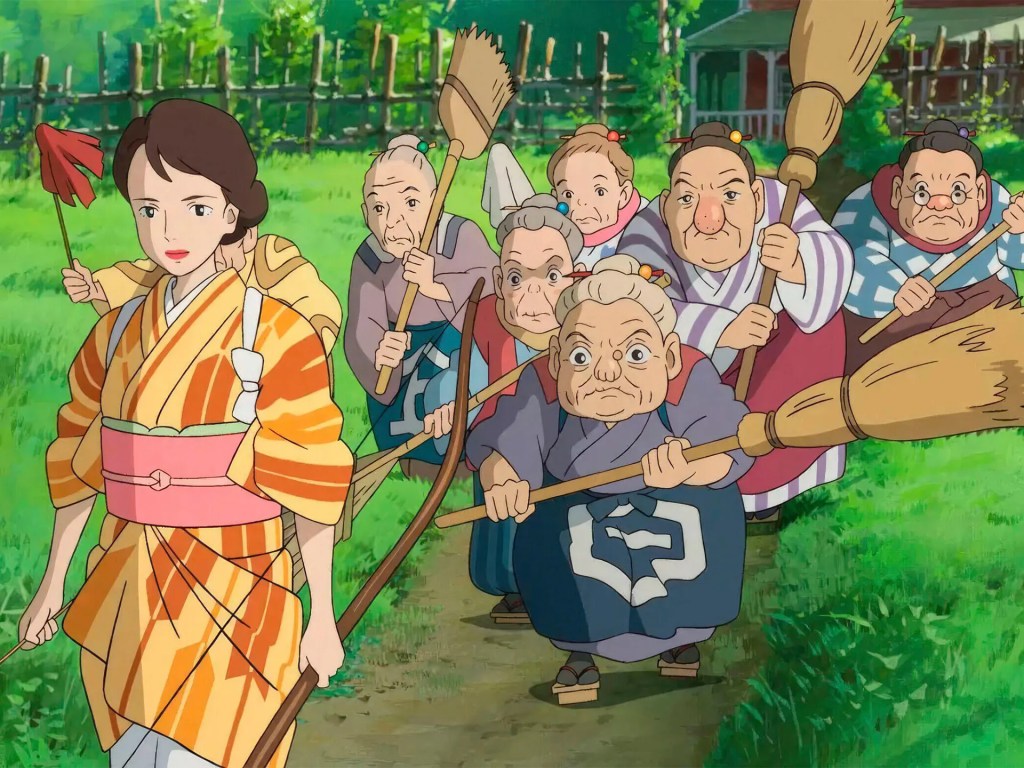

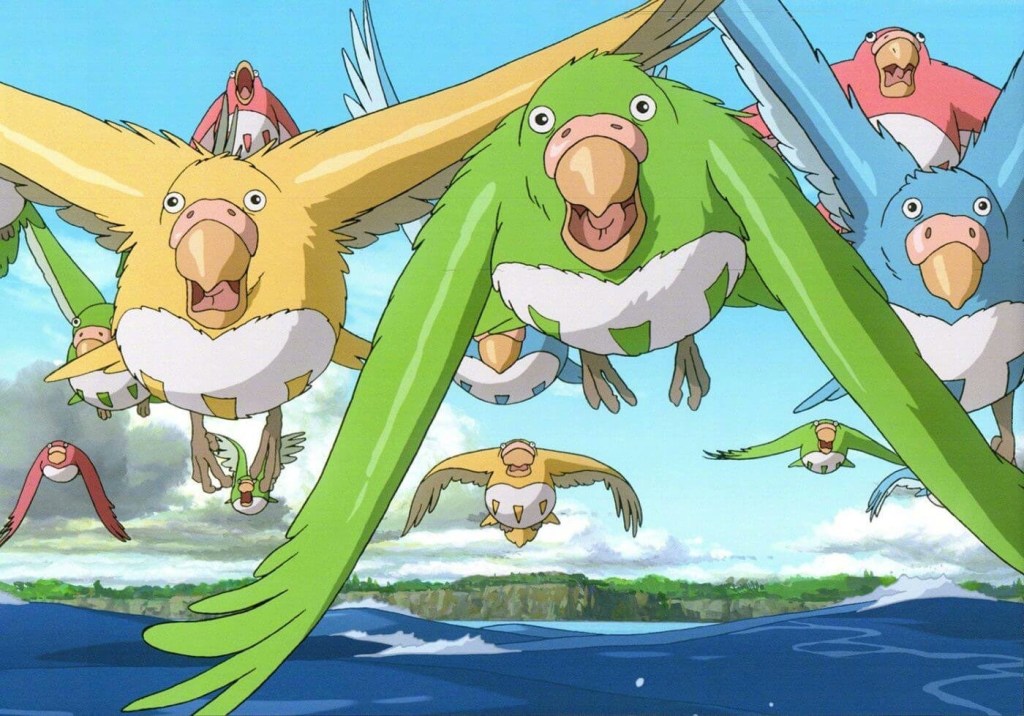

While I do wish The Boy and the Heron had worked on that level for me throughout, I am nonetheless grateful to have had the opportunity to see another film by Miyazaki released at cinemas. The long stretches where it just worked for me on an emotional level more than made up for the final third and its narrative clutter – and even there, I may not have felt that I’m really understanding the details of what was happening, but I was still able to enjoy the beauty and the strangeness, the De Chirico-style spaces, the murderous parakeets (there are so many birds in this! and scary birds, at that!), the seven weird old women, the most badass fisherwoman in all of cinema, and that strange, strange heron who may not be a heron at all. Even when we may not always understand everything, we’ve been lucky to experience the world through Miyazaki’s eyes.

2 thoughts on “The sound of wings: The Boy and the Heron (2023)”