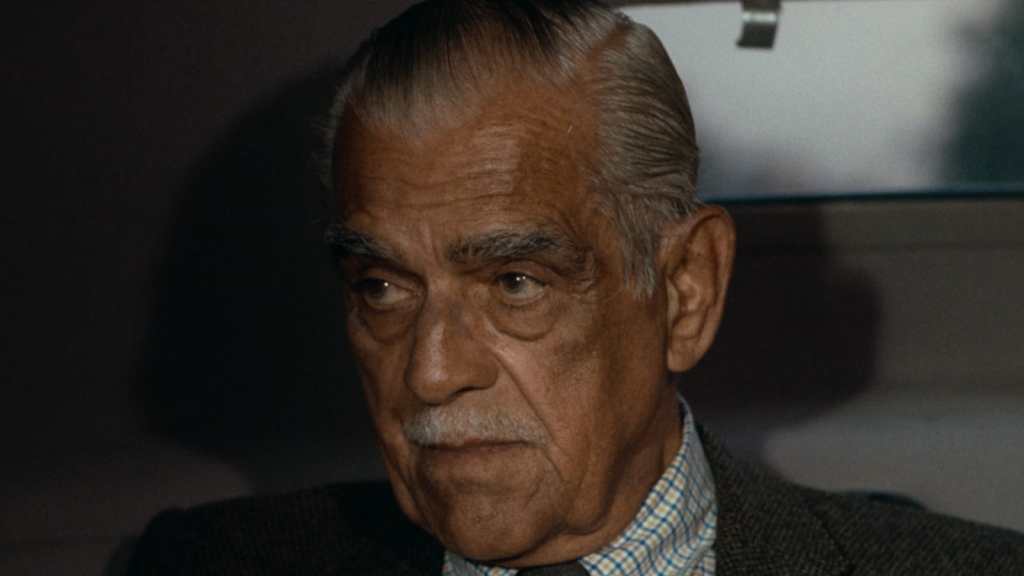

It’s the kind of meta filmmaking that’s catnip for critics and academics: screen legend Boris Karloff, firmly at the tail end of his career as a horror movie actor, plays the equally legendary Byron Orlok, a man firmly at the tail end of his career as a horror movie actor. Orlok announces his retirement from cinema, because he’s a has-been and his brand of cinematic horror is no longer scary, it’s camp. Meanwhile, a thoroughly modern kind of bogeyman stalks Los Angeles County: a young, blandly all-American insurance agent with an unsettlingly large gun collection, takes aim at random targets. Slowly but surely the two storylines converge, until they intersect – in a drive-in cinema, where Orlok is set to make his final public appearance. It’s cinema all the way down.

While I’m exactly the target (ha!) audience for Targets in one respect, in another I am very much not: while I do have a keen interest in metafiction across various media, until four or five years ago I’d not seen a single Boris Karloff film. Sure, I was aware of him having played the iconic version of Frankenstein’s monster for Universal, and I’d seen all the stills and backstage photos, but I’d never actually watched Frankenstein – though I’d seen both Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters (a period drama about James Whale, the director of Frankenstein and its sequel Bride of Frankenstein) and the 1970s Spanish drama The Spirit of the Beehive, two films for whom the Boris Karloff movies are an important intertext. (Hey, it could be worse: I could be a former EngLit major who’s never read the original novel by Mary Shelley.) Karloff was ‘my’ Frankenstein much as he was my generation’s (and yes, I know, Frankenstein isn’t actually the monster’s name), but it was all just second-hand knowledge. I’ve since made up for this somewhat, having seen Karloff in Frankenstein as well as in The Mummy, but it’s definitely my fellow cultural baristas at A Damn Fine Cup of Culture that have much more knowledge of, and immediate affection for, the classic movie monsters, whether they’re Universal, Hammer or any other flavour.

Another relative gap in my movie experience: Peter Bogdanovich – although the “relative” carries a lot of the weight in that phrase. I’ve seen What’s Up, Doc and Paper Moon, although in my early teens, and I did later catch up with The Last Picture Show and The Cat’s Meow, and possibly even with Noises Off, but other than The Last Picture Show I don’t much remember any of these. For me, Peter Bogdanovich is first and foremost Doctor Melfi’s psychiatrist on The Sopranos, so whatever clever joke that casting choice constituted was wasted on me.

Still, when Criterion announced its release of Targets, I was intrigued – less immediately because of Bogdanovich or Karloff than because of the film’s themes. This, combined with my famously itchy trigger finger when it comes to ordering Criterion releases, made me order Targets the moment it came out last year, but I only got around to actually watching the film in early 2024.

Targets starts promisingly enough with a cheesy horror pastiche bordering on camp, starring has-been horror actor Orlok. (My relative ignorance of horror movies from the time meant that I thought the scenes from the film-within-the-film had been made especially for Targets, but the excerpts are in fact from The Terror, a 1963 horror movie made by Roger Corman – with uncredited directorial help from the likes of Francis Ford Coppola… and a very young Jack Nicholson, who also stars as The Terror‘s heroic lead.) That additional twist in the metafictional tale soon gives way to a conversation in the screening room, where no one seems particularly excited about the film they’d just made, but everyone tries to mollify Orlok, who is more than just disappointed with his latest work: seeing this kind of dated horror likely to elicit laughter rather than screams from a ’70s audience only confirms him in his decision to retire from the movies.

However, apart from the Corman intro, for the first half hour or so my impression of the film wasn’t positive. In terms of the writing, acting, lighting, cinematography, the first actual scene of Targets that wasn’t The Terror fell flat for me. It felt bad, even amateurish – almost like a parody of inept filmmaking, and more than that, it felt like bad television rather than bad cinema. Having Bogdanovich himself play a big supporting part (as Sammy Michaels, the writer-director of Orlok’s latest, and likely last, schlockfest) didn’t exactly help. Was this knowingly, purposefully bad, or was it the filmmaking of a young writer-director who was simply not good enough at his craft at this point to do the material justice?

Once soon-to-be killer Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly) enters the picture, things change – or they shift. The flat, TV-like filmmaking persists, but as we see Thompson’s suburban world, there seems to be a point to it. There is a profound sense of unreality to the world Thompson and his wife, who are living with his parents, inhabit. Even while he tries to keep up appearances, the man’s disconnect from the world becomes more and more palpable, so when he finally turns his guns first on those closest to him and then on random people, the effect is shocking but not really surprising. As he aims down the sight at cars driving by, Thompson doesn’t seem to have undergone a change so much as he’s finally able to live as what he’s been since the beginning: an all-American nightmare.

Verdict: If I’d been asked during the first half hour of Targets what I thought, I wouldn’t have been terribly positive. There is a self-satisfied quality to the film’s meta setup that feels glib, even if Karloff’s grumpy old man is engaging, and seeing the director also acting in his own film rarely helps. Something feels off about the filmmaking in the early scenes of Targets, and I’m still not sure whether this is intentional, trying to achieve a specific effect or commenting on Byron Orlok’s latest film not being particularly good itself. Once the film’s deeply disconnected Charles Whitman stand-in is introduced, though, things start falling into place and Targets finds its groove. In its middle third, the film becomes deeply unsettling, arguably more so because the filmmaking isn’t overtly cinematic (except for a handful of stylistic flourishes). Thompson’s killing spree isn’t punctuated by an orchestral soundtrack telling us how to feel about what is happening, it happens with the same flat affect as the early scenes depicting his family life. However, it’s in the film’s final third, where the two storylines converge, that the filmmaking can be seen at its most ambitious and effective and Targets‘ commentary on film, violence and horror really clicks. It is here, and looking back at the way Targets builds up its story, characters and themes, that the film feels almost like a B-movie mash-up of Sunset Boulevard and Peeping Tom, though one with a flavour very much of its own.

One thought on “Criterion Corner: Targets (#1179)”