Wikipedia describes Man with a Movie Camera, directed by Dziga Vertov, filmed by his brother Mikhail Kaufman and edited by Vertov’s wife Yelizaveta Svilova, as an “experimental 1929 Soviet silent documentary film”. What kind of images does this conjure in your mind? My knowledge of Soviet art isn’t particularly broad, but it’s biased by what I’ve seen of Soviet propaganda: heroic, productive workers, didactic visuals showing us what the ideal communist world ought to look like. A utopia that, with the benefit of hindsight, often looks phoney, frightening or both.

Whatever I might have expected of Man with a Movie Camera, it’s very different from what the film actually is: an audacious, joyful approach to an art form that, even 36 years after its birth, was still in its infancy in many ways.

In 2023, the best cinema in the world (well, the best cinema in my world) showed Mikhail Kaufman’s 1929 film In Spring, accompanied live by the Ukrainian musicians Roksana Smirnova (piano) and Misha Kalinin (guitar). A few weeks ago, they showed Man with a Movie Camera in the same constellation. Truth to tell, while I was curious about the film – and the live performance -, it was more of an intellectual curiosity: I expected something strange, removed from us in time and space, a cultural relic from a bygone era. In Spring had been fascinating, but it hadn’t captured my imagination.

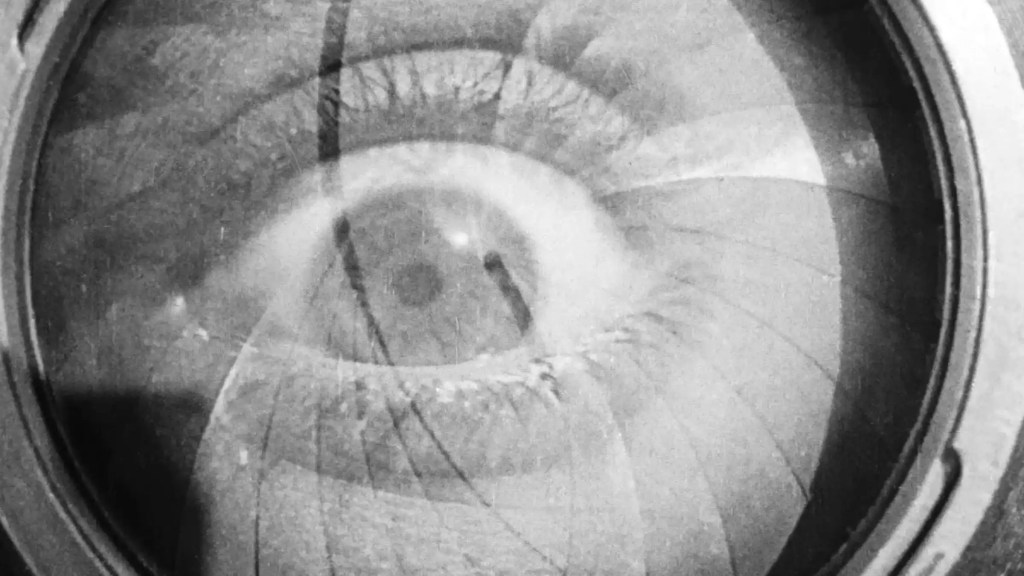

Man with a Movie Camera is similar, but it has qualities that go beyond In Spring. ‘Timelessness’ isn’t quite the right word to describe Vertov’s film: it’s more that it feels of the present in a less tangible way. Older films feel old to a large extent because of the conventions they follow: how they use the camera, lighting and editing, how they film people and action. The more films we watch from a certain time, the more we recognise those conventions – and we also recognise it when a film from a certain time and cultural context breaks those conventions. Man with a Movie Camera, on the other hand, feels like it is operating outside conventions: it’s less experimental in a way that communicates an artistic ideology than in the way that child’s play is experimental. The overriding sense is that Vertov, Kaufman and Svilova are out to find out what this medium can do. And while the material they’re working with is documentary – Man with a Movie Camera mainly shows scenes of life in a number of Ukrainian cities in the 1920s -, the approach is something else altogether. It is as if these artists came together and asked: What if we do this? What if we do that? What if we cut images together like so? What if we film them like this? There’s a sense of exhilaration – and, at times, even of danger, as we see Kaufman, the titular man with the movie camera, put himself in positions that don’t look altogether safe in his hunt for new and exciting shots, in high places, on cars driving at considerable speeds. Some images are startlingly mobile, others are direct and unvarnished (in a way that I definitely wouldn’t have expected from Soviet cinema, or any cinema, at the time – e.g. a live child birth), and yet others seem like precursors to VFX-heavy films folding space and time such as Christopher Nolan’s Inception. There is no coy sense here that we are watching the experiments of a time long gone that in the 21st century seem quaint. Man with a Movie Camera maintains its freshness today.

Moreover, there is a strong sense of self-reflexivity that adds to the film’s freshness. It doesn’t take its form for granted, and it doesn’t try to hide its identity as a cinematic artefact either. Many of the shots are followed by companion shots showing us Kaufman capturing that very same sequence – and I couldn’t help wondering about the camera and cinematographer capturing the camera and cinematographer shooting Kaufman with his camera. Where does it end? Is it men with movie cameras all the way down? And women too, though as so often seems to be the case, they’re the ones in the editing booth. Man with a Movie Camera shows us shots of a woman working with strips of films, cutting them, recombining and remixing them. Svilova editing scenes of Svilova editing, cameras capturing cameras capturing other scenes of city life: if Man with a Movie Camera has as its subject and theme modern urban life, then the makers of the film clearly believe that modern life cannot be imagined without filmmakers and cameras being a part of it. One wonders what these artists would think of our present, where practically everyone carries a movie camera around in their pockets!

What should not be forgotten in this context, though, is the effect that the music has. I’ve not seen many silent films accompanied live by musicians that are present and visible to the audience, but the few times I’ve been lucky to see such a performance, it’s always struck me how different this feels from a concert that happens to have moving images in the background. There is a freshness but also a strange, vulnerable nakedness to such a performance that extends to the film, so that it too starts to feel live to me, even though it is obviously a recording. The interaction of the film and the music creates something different yet again. Smirnova and Kalinin’s music in many ways is more of a soundscape than conventional movie music: they create a vibe rather than clearly recognisable melodies. There is also no Mickey Mousing, as you may get with music accompanying a silent slapstick movie, even though the images of Man with a Movie Camera could probably be accompanied by more immediately reactive, literal sounds. Nonetheless, we read the film differently because of the music, the tone and indeed the feel of the visuals changes, almost to the point where I imagine that Man with a Movie Camera could end up feeling like a very different film if accompanied by different music. There is almost a sense here of the music and the images entering into a Kuleshov effect-like relationship: happy, joyful people on the beach or busy city scenes read differently if the music is pensive, dreamlike.

I can absolutely recommend Man with a Movie Camera to anyone with even a passing interest in the art form – but even if you watch the film, you won’t be watching quite the same thing as I did. When you see it, the music may be live or recorded, it may even be the same musicians that we saw (Smirnova and Kalinin have been touring Europe, accompanying various silent films live), but adding a layer of live performance makes the whole combined work of art take on a live quality – which absolutely underlines what Man with a Movie Camera is at its core: not a historical document, although it clearly is that too, not something to be put in a museum where it can be looked at together with all the other relics, but something alive and present, something that speaks of a now, and that speaks to us in our own now. In so many ways, Man with a Movie Camera never feels anything other than: live.

One thought on “Sight and Sound: Man with a Movie Camera (feat. Roksana Smirnova and Misha Kalinin)”