When it comes to the inventions that changed the world, what are the ones you think of? I suspect that most would come up with the likes of the wheel, the printing press, and the steam engine, electricity and the computer. But what about the device that has perhaps become more ubiquitous in the last twenty years than any other: the camera? While it is likely that fewer people own an actual, bespoke camera in 2024 than at the beginning of the millennium, everyone who owns a phone has in their possession a powerful device that can record still images as well as moving pictures, and people make use of this to an extent that would have been unthinkable before the smartphone. We’re all photographers and filmmakers: an estimated 5 billion photos are taken on a daily basis, and 3.7 million new videos are uploaded to YouTube alone every single day. What are the effects of this? Is the world different when you’re looking at it through the lens of a camera? Or, to ask differently: Are we different when we’re looking at the world, and at ourselves, through the lens of a camera?

Last week, on a trip to Berlin, I took a fair number of photos myself, and I recorded a video or two. I also saw two films that, while they belong to very different genres, share some startling thematic links. Both films left me with similar feelings: exhilaration blended with unease, both of which slowly gave way to an underlying frustration. The two films are made with great skill, and they are undoubtedly engaging – but each has an emptiness at its centre that results perhaps from wanting to depict certain ideas while being largely unwilling to take an actual position. The films raise questions, but they go out of their way not to have any answers of their own, except for the most basic ones. At best, they present their audiences with structured spaces to reflect; at worst, both films, in spite of everything they do well and smartly, end up being little more than mirrors for the audience – and not necessarily mirrors in which we may recognise ourselves being reflected, but mirrors that show us whatever we wish to see.

The first of these films was made by the writer/director duo Axel Danielson and Maximilien Van Aertryck and bears the wonderful title And the King Said, What a Fantastic Machine (generally abbreviated to Fantastic Machine, which sounds a bit like an oddly exuberant name for an otherwise generic superhero). It tells the story of humanity’s love affair with the camera, starting with the invention of photography in the 19th century, then moving to the moving picture and beyond, touching on the Camera Obscura, the Lumière brothers and the Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl (in footage that is chilling in how enamoured the old Riefenstahl still is with her work and her achievements as a filmmaker while entirely ignoring/denying the reality of what she was in fact doing). However, the main focus of Fantastic Machine is the smartphone era, in which everyone can be both a filmmaker and a star. Several sequences focusing on influencers who basically live their lives online, parents who share their children’s traumatic experience of witnessing the death of Mufasa (father of The Lion King‘s Simba) with the world, January 6 insurrectionists taking proud selfies grinning into the camera while ransacking the Capitol, people seeking thrills as much as clicks by shooting and posting videos of themselves hanging precariously from buildings hundreds of metres high. There is a memorable scene found on the equipment of an IS group that had recorded a recruitment video, and their outtakes prompt laughter from the audience startled at the familiarity of how these men behave on camera – forgetting lines, being upstaged by animals, corpsing when things don’t go as planned -, but then the laughter sticks in our throats as we remember the actual corpses that result from the activities of IS.

Fantastic Machine‘s main skill lies in how it selects and juxtaposes clips. However, it is relatively rare that the film comments, by means of voiceover, on what we’re seeing, and when it does, its comments barely go beyond an implicit “Makes you think, doesn’t it?” This allows you to read into the film exactly what you bring to it: if you’re afraid of the effect that smartphones, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok have on impressionable minds both young and old, that’s what you’ll find in the film. If you consider all of this an expression first and foremost of the many ways in which human beings can make fools of themselves, Fantastic Machine shows you just that. It’s not that it has no position at all: it definitely suggests that there is something ominous about this age in which we are constantly watching others while being watched ourselves, but it is happy to limit itself to the vaguest hints only of a thesis or an opinion on the things it shares with the audience. It’s ‘just asking questions’, so to speak. And it undoubtedly does so in ways that are entertaining and that can provoke thoughts, but the thoughts it provokes are probably the ones we already have. It’s not that it is objective or unbiased or neutral so much as it is strangely empty. It wiggles its metaphorical eyebrows to insinuate meaning, rather than putting much work into meaning anything. I have no doubt that Fantastic Machine is wonderful at generating conversations, but like so many facilitators skilled at their job it may not have all that much to say itself.

In terms of look and feel, Alex Garland’s film Civil War (which Garland has said may well be his final film) couldn’t be more different from Fantastic Machine. The latter is often archly comic and designed to elicit laughter, though this may be uneasy at times. Civil War is thrilling, tense, harrowing. Where Fantastic Machine‘s tone can veer towards the glib (it isn’t altogether surprising that the film was co-produced by Ruben Östlund, director of Force Majeure and The Square), Garland’s film is pretty much unrelenting in its grimness. What humour there is to be found is of the gallows variety.

Civil War tells the story of a quartet of journalists on the way to Washington, D.C., where they intend to interview and photograph the president. What makes this more difficult to achieve: the United States are in a state of civil war. The president leads an authoritarian government, and various regional factions have arisen to resist, among them the Western Forces made up of Texas and California. Much has been made of this seemingly nonsensical team-up, but it indicates what Civil War does and does not set out to be. Garland isn’t making a film about the concrete present-day tensions in the US, he’s not trying to say anything about Trump or MAGA, about red states and blue states, about liberal democracy vs the nascent fascism of the alt-Right and the Republican Party. The closest the movie comes to talking about the present day in this respect is that Garland depicts a nation torn apart by factionalism, regardless of what those factions stand for. He and his film have been criticised for being apolitical, but I don’t think that this is quite accurate: Civil War isn’t about party politics, but it is not apolitical, even if it is broad and nonpartisan to the point of becoming woolly in its politics. It is political in the abstract only, and that abstraction is both freeing and limiting.

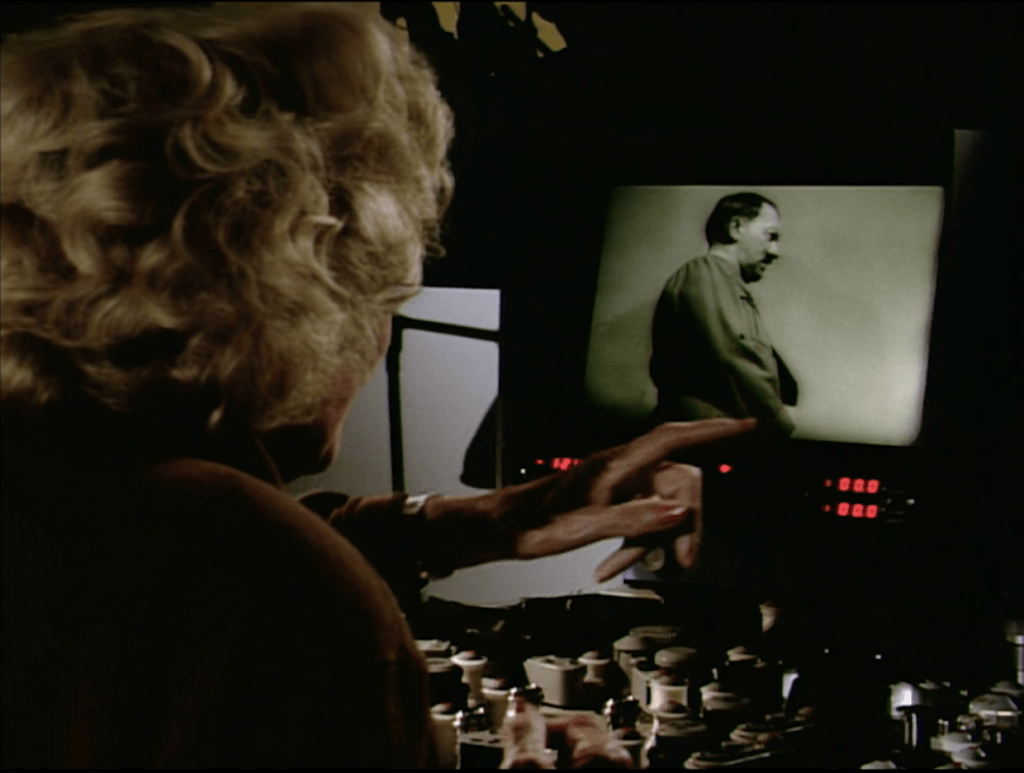

More than anything concretely political, Civil War is about the ethics of (photo-)journalism, in particular when it comes to depicting the unethical. There is a sequence in Fantastic Machine that provides a coincidental but perfect framing for Civil War: we are first shown the famous photo of 15-year-old Fabienne Cherisma who was shot while scavenging for supplies following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, then we see the same scene from a different angle: a half-dozen of photographers a small distance away from the dead girl, pointing their cameras at her, like so many vultures waiting to tuck into their dinner. Can the actions of these journalists be justified? What are the ethics of standing there and taking photos while people suffer and die? Wouldn’t the right course of action be to help? Civil War addresses this directly through its main character Lee (Kirsten Dunst): “Once you start asking those questions, you can’t stop. So we don’t ask. We record so other people ask.” But it doesn’t necessarily take this to be the final word on the matter. Throughout the movie, we see the four journalists in different states and roles: they’re adrenaline junkies one moment, silent witnesses the next, they’re traumatised participants, they are put in a position to decide over life and death, then they are powerless to change anyone’s fate, let alone their own. Are they recording so that other people ask the right questions? Or are they recording because that is their raison d’être, and everything else is incidental? What is a photojournalist when they don’t take any pictures, if they weren’t taking that photo of a dying soldier, a tortured civilian, a pathetic, helpless man about to be executed? It is not incidental that perhaps the lowest moment of Civil War‘s protagonists comes when it looks like others might get to the president first, and that their journey has most likely been for nothing. To them, it doesn’t matter that someone records these things, it matters that it is they who do the recording, who beat everyone else to the scoop.

Like Fantastic Machine, Civil War is never less than watchable. Even if Garland has little to say about present-day America, it is tremendously effective to see the kind of images we’re used to seeing set in such a familiar context. We’ve seen these pictures, but set in the Middle East, or some African country, or perhaps some place in Latin America where gangs are in control. They don’t have anything to do with us. We can gawk and judge and get all the vicarious thrills we want. It’s different if the pictures are set in a place that we recognise as our own, or as reasonably similar. It’s more intimate. We realise that those depicted in the images, those dead or dying or traumatised, could be our friends, our families, ourselves.

Civil War‘s power lies in its approach to its subject matter. It is entirely experiential: most of the time, it doesn’t step back and comment on what it’s showing us, except in a few moments when it spells out its themes. (The film’s ending is one of those moments, and it is one of the few that fell entirely flat for me due to its heavy-handedness.) And that’s also where Civil War‘s strengths lie. The few moments when it approaches something of a theme are perhaps its weakest: war is hell and civil war doubly so. Journalism can be ethically dubious, and the people who bear witness may not be doing so out of the goodness of their hearts. The way Garland goes out of his way not to allow for a reading against the backdrop of 2024 suggests that he thinks he has more important things to say, but in the end, Civil War ends up saying relatively little. On a moment-to-moment basis, it is a brilliantly crafted war drama, but when you’re not in the moment any more it becomes strikingly trite.

In the end, both of these films about our queasy, passionate, headless affair with the camera, and the ways in which it affects us, are worth watching – as long as you don’t expect them to to be capable of provoking much thought. Each is engaging and effective while you’re in the moment, and they can undoubtedly prompt conversation and debate, but they don’t contribute all that much to that conversation. Neither really has all that much to say, even if both Fantastic Machine and Civil War certainly have the surface appearance of depth. To put it in terminology that fits the subject: each of these films ends up having a surprisingly shallow focus.

One thought on “Through a lens darkly: Fantastic Machine (2023) and Civil War (2024)”