Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: pupils from a girls’ school in Australia go on an outing to a nearby geological formation. Some of the girls go to explore the area – and disappear. One turns up later, with no memories of what happened. The others remain gone. No traces are found, no blood, no bodies. Nothing.

The mystery is never solved. And it is this, not knowing what happened, that begins to corrode the lives of those left behind.

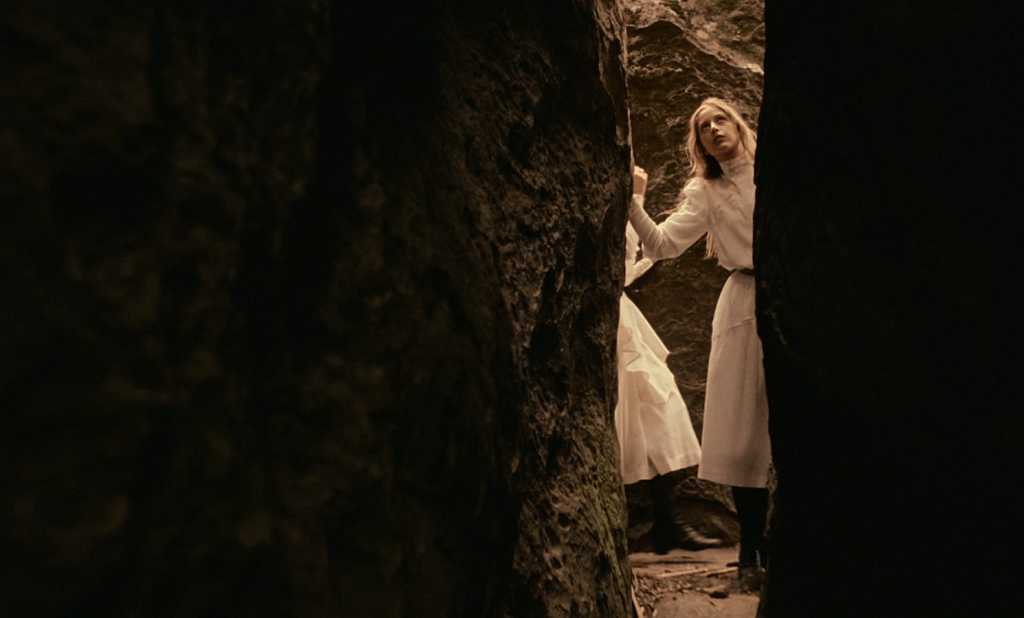

In some ways, Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock is the ultimate mystery box. Here are the girls that climb the rock and vanish into a crevice, and we never see them again – but there are possibilities. Was it the two young men ogling the girls from a nearby copse, clearly fascinated with them? Did they get bitten by the poisonous snakes that are mentioned repeatedly, and then wander into one of the many nooks and crannies of the Rock? This is Australia, a country that’s pretty much become a meme for its deadly fauna and flora, a place that is very much not made for the British who have made it their home and who have tried, unsuccessfully, to make it look and feel just like Old Blighty. In some ways, it would be a bigger mystery if the country didn’t take its toll in blood. These girls can’t just have vanished, it’s just a matter of finding their remains.

But mystery boxes are made to be solved, and that is the last thing Weir’s film is interested in. It isn’t even really about the vanishing so much as it is about the hole such an occurrence leaves behind, the disappearance of the girls as much as the inexplicable nature of what has happened. The colonial late Victorians pretending that this continent they’ve made their own is just an extension of the home they have left behind. They cannot deal with a world that they cannot understand: if we cannot measure and analyse and comprehend, then anything can happen to any of us at any time.

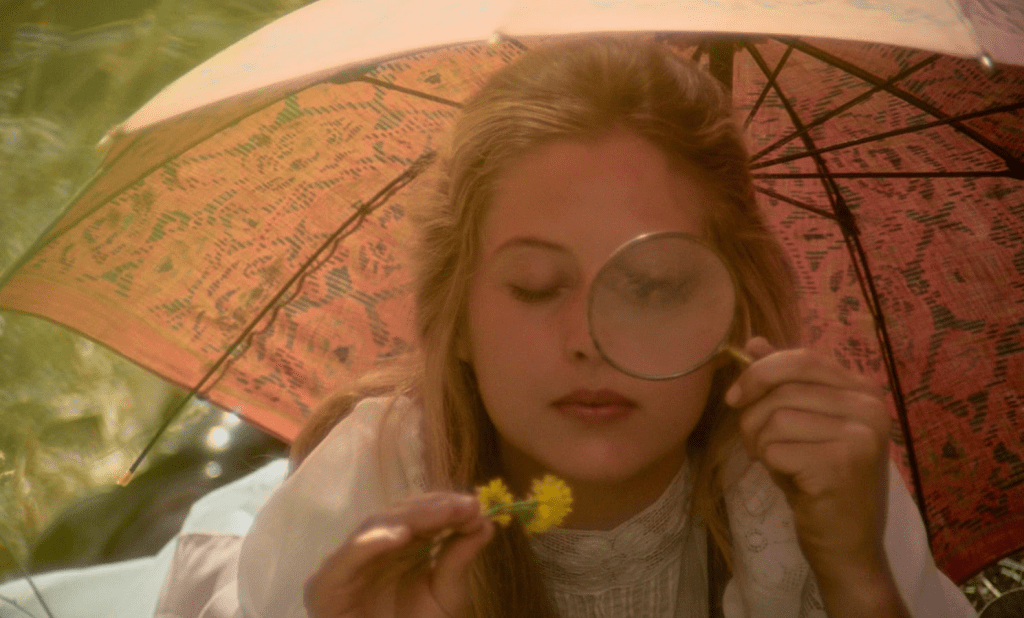

I think I first saw Picnic at Hanging Rock when I was a teenager, and while it left me fascinated, my memory of the film, much as the characters’ memory of the girls, was hazy, as if through a filter. The Picnic at Hanging Rock that I remembered looked not unlike those soft-focus (and sometimes soft-porny) pictures by David Hamilton: nubile girls shot through a film of Vaseline, something to desire and long for, something other and all the more alluring for it. I was surprised to find that while Weir’s film uses such imagery a couple of times, it is usually when we see the girls through the eyes of others, or in their recollections. It is only then that they become these ethereal, idealised creatures. The imagery of the film for the most part is strange, but it is also concrete, making the girls as physical and real as the rocky landscape they find themselves in. In the early scenes of the film, the girls stand out as literally foreign bodies in the hot, alien landscape – but the sequence that leads up to their vanishing sees them becoming more and more a part of that world. They take off their stockings, they explore, they enter – but with curiosity and fascination, not with the need for conquest more typical of their male contemporaries. It is as if they gain access to a place that doesn’t need to be made homely by means of Victorian architecture and paintings and porcelain and lace doilies. Wherever they have gone, others cannot follow, because they’re unprepared to see this place to begin with. Australia’s supposed to be a canvas on which the colonisers can paint the world they’ve left behind: but it turns out to be something very different, a world that only truly accommodates those who are willing to become a part of it.

Verdict: Picnic at Hanging Rock remains a fascinating film. Even if you accept that it isn’t about answers, that it won’t uncover its mysteries to you, it is tremendously difficult not to read it for signs as to what could have happened and what all of this means. Like Hanging Rock, the hole at the centre of this film stands there, impossible to understand and impossible to ignore. Watching the film in 2024, it reminded me, in terms of its vibes more than anything else, of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s enigmatic Memoria, in which Tilda Swinton plays a character who finds herself the only one to hear a loud boom. Differently from Peter Weir’s classic, Memoria offers an explanation for its central mystery – but that explanation is even less comprehensible than the mystery itself.

The 4K version of Picnic at Hanging Rock that Criterion released earlier this year is absolutely gorgeous, highlighting the detail and texture that in my memory had been hidden behind a diffuse filter, making everything more vague than it actually is. But although the film isn’t vague, its beauty and detail leave things just as unexplainable. What makes Picnic at Hanging Rock so endurable is that it offers multiple approaches to the question it poses. We can read the girls and their exploration of Hanging Rock in Freudian terms: adolescence and discovery of a place from which there is no return. We can look at it through the lens of gender, or examine it from a (post-)colonial angle. But while all of these perspectives are valid, they will not get us closer to what it is the girls found on the Rock, on the other side of that crevice. The niggling itch of not knowing remains.

One thought on “Criterion Corner: Picnic at Hanging Rock (#29)”