There are so many iconic directors that came out of the Nouvelle Vague, the French New Wave. Obviously there’s François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, and even if you don’t like either or both, there’s no getting past them. Then there are the likes of Rohmer and Rivette, and others associated with (but not always counted as part of) the Nouvelle Vague, such as Resnais, Demy or Varda.

And then there is Claude Chabrol, who stands out for his dedication to genre cinema, something that is rare in the movement. He is one of the directors I’ve been aware of for a long time, but I had only seen a couple of films: The Colour of Lies (original title: Au coeur du mensonge, translated more accurately as At the Heart of the Lie), a thriller that I enjoyed at the time but that didn’t leave all that much of a trace, and the Highsmith adaptation The Cry of the Owl (Le cri du hibou), which I absolutely hated. Highsmith should be a good fit for Chabrol, but this particular adaptation didn’t work for me, leaving some characters utterly vague, others grotesquely one-note, and all of them annoying. (I later saw the more recent English-language version with Paddy Considine, which was almost aggressively mediocre but nonetheless felt like an improvement on Chabrol’s take.)

Because of this, I went into La Ceremonie with some trepidation: would I bounce off as much as I had with The Cry of the Owl? Does Chabrol just not do it for me all that much? Should I go back to the less genre-minded members of the French New Wave?

I’ll cut it short: even if I’d not seen any other Chabrol films at all – hell, even if I’d only seen, and hated, The Cry of the Owl -, La Ceremonie‘s strength would be enough to make me a fan. This is a definite keeper – that is, if you’re okay with thrillers that leave you feeling deeply uneasy for days.

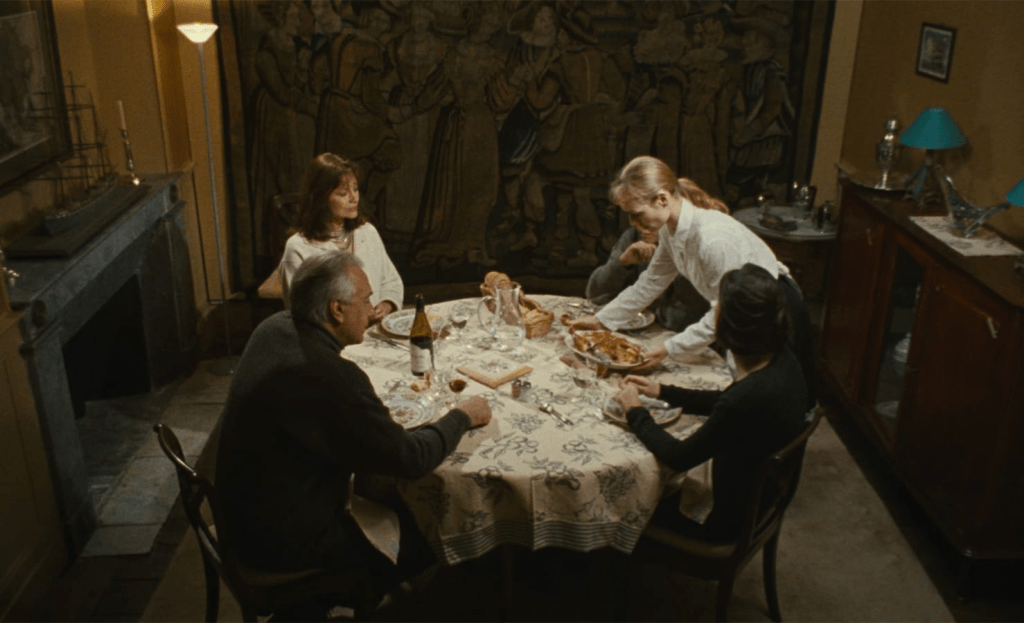

In La Cérémonie (based on the novel A Judgement in Stone by Ruth Rendell), Sophie, a young woman (played by Sandrine Bonnaire with a brittle detachment) is hired as a maid by the Lelièvre family. The Lelièvres are pretty much what you might expect of a well-off French family in a thriller: they live in a lavish mansion, they’re well-meaning but patronising towards those who clearly haven’t had their means and privilege, they’re kind and generous but in ways that are likely to make you roll your eyes. They talk about Sophie, not unfavourably, but they do so while the woman is two rooms away, hearing every word. They see themselves as subjects, but to them Sophie seems to be an object. They are aware of the ways in which Sophie is less fortunate than they are and offer to pay for her driving lessons and appointments at the optician, but they don’t much seem to see Sophie – and Sophie isn’t particularly forthcoming. The young woman is guarded to the point of rudeness almost – and, to be honest, she is a more than a little odd. She avoids using the dishwasher, she refuses the offers for driving lessons. There seems to be a disconnect between her and the world – and this is where we get into spoiler territory, so if you haven’t seen the film, go and do so, and then come back.

The film spends some time building up Sophie’s oddness before it reveals the reason for it. Sophie’s brusque aloofness isn’t just a way to protect herself, nor is she simply rude or socially inept: she is illiterate. Sophie does not reveal the reason for her behaviour, but neither does she care to change her situation. She deals with it, albeit in ways that seem irrational and that put her at odds with others. And, on top of that, she has a possible history of violence: her disabled father died under mysterious circumstances while in her care.

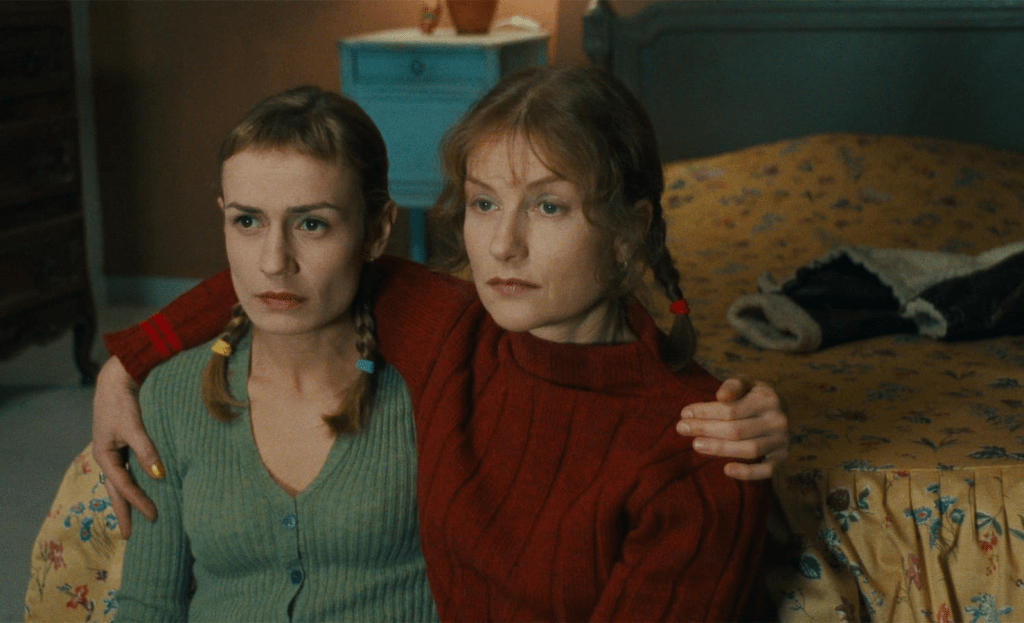

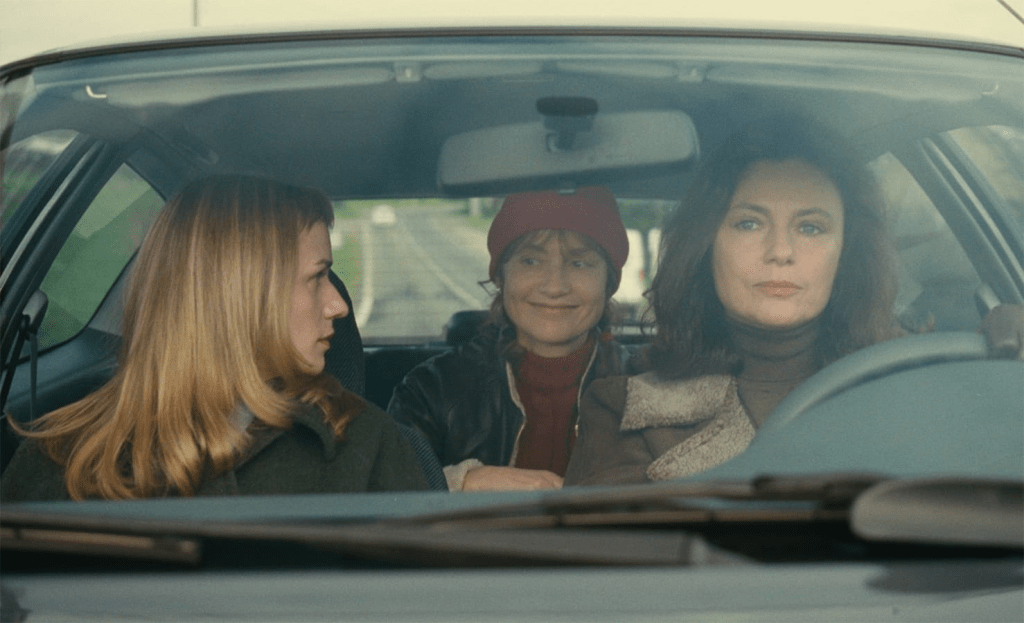

The Lelièvres don’t manage to penetrate the wall that Sophie has put up around herself, nor do they care to after a while: the young woman is strange, but she does a good enough job. They’ve offered to help, sometimes in ways that intend to be kind but that set your teeth on edge in how condescending they are, so what more should they do? One person does manage to befriend Sophie, however: Jeanne (Isabelle Huppert), the postmistress, a woman with few friends with a shady past of her own – there is the distinct possibility that Jeanne killed her own daughter, but she was never convicted. There is an almost manic messiness to Jeanne, and an almost adolescent decision not to engage in the niceties of conventionality. But as Sophie and Jeanne become close friends, it becomes clear that there is more going on here than just a friendship between two outsiders: each reveals the darker sides in the other, the resentment towards the bourgeoisie, the Lelièvres of this world, and the potential for more than just resentment.

Verdict: I don’t want to write too much about the plot details of La Cérémonie, because a lot of the enjoyment comes from watching all of this unfurl and culminate in a climax that is both nauseating and oddly liberating, but there is no going around the ending. Chabrol has jokingly called La Cérémonie “the last Marxist film”, and it is this quality that will rub some people the wrong way – because it culminates in an orgy of violence that is uncomfortable to watch, by the two women against the affluent Lelièvres. Sophie and Jeanne kill every member of the family: the mother Catherine (Jacqueline Bisset), the father Georges (Jean-Pierre Cassel), and the two children Melinda (Virgine Ledoyen) and Gilles (Valentin Merlet). Is it fair? Did the Lelièvres deserve it? Are Sophie and Jeanne warriors, trying to right the wrongs of a classist society where the gap between the haves and the have-nots keeps widening, and where patronising gestures of generosity only reinforce that gap? None of this is the case. The family becomes more and more offputting in its condescension, and at times they almost veer towards class caricature (the night they are killed, they sit down in front of the television, all dressed up, to watch an opera on TV, with Georges exclaiming excitedly: “Mozart, here we come!”), but does this warrant death? And the two young women: while there is no certainty, most likely each of them killed a family member dependent on them, or at least they let them die. They are no avenging angels, their cause is not just – but it is too easy to condemn them wholly and to let the Lelièvres off the hook. The latter are not monsters, deserving to be the first against the wall when the revolution comes, but they’re a symptom of a society that’s rotten. And it is the monsters that the society has created that will come to haunt them.

The flipside of this is that, while Sophie and Jeanne may be regurgitating this rot, lashing out against those with privilege, they are not good people, and their actions are not revolutionary. Their resentments express themselves in a revenge that will only serve to reinforce the structures that cause that resentment to begin with: obviously good, rich people have to defend themselves against such envy, obviously murderers have to pay for their crimes. The climax of La Cérémonie is cathartic, but it is a dead end, in more ways that one.

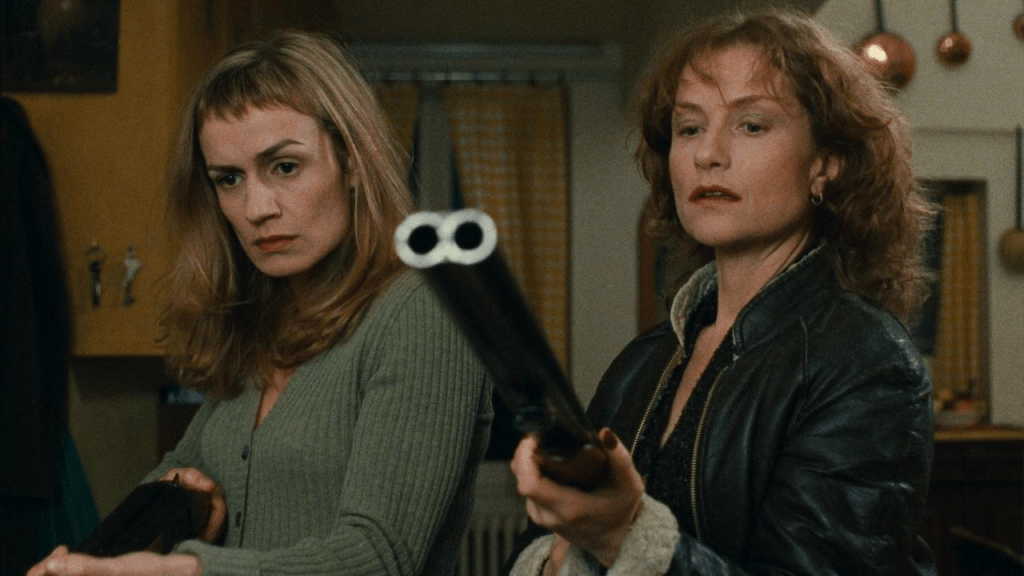

But this makes the film sound grimmer than it is. It’s definitely not light fare, but there is an impish fun in watching especially Isabelle Huppert in an unusual role. Huppert rarely plays characters that submit to the dictates of society, she usually deals in irony and subversion, but coming at it from the end of her career, we more often see her living in the mansions rather than invading them with a loaded shotgun. In La Cérémonie, la Huppert is a rude, selfish chaos goblin that does not care what others think of her and her actions – whether those actions are opening other people’s mail, letting her troublesome daughter die (or killing her in a more active way?) – or taking out her used chewing gum, sticking it under a desk, and then popping it in her mouth and continuing to chew! She is a Francophone variation on characters like Barbara Loden’s Wanda, crossed with the sociopathy of Badlands‘ Kit or Peter and Paul from Michael Haneke’s Funny Games. She has found the fun in giving the finger to social conventions – and after she’s given them the finger, she follows that up with two blasts from a shotgun.

And it’s this that makes La Cérémonie so deliciously uncomfortable: we enjoy watching Jeanne as she offers Sophie a release valve… but really, if we’re honest about it, most of us are probably the Lelièvres in this story. We sit on the sofa watching, well, perhaps not a performance of Don Giovanni but a classic psychological thriller by Claude Chabrol, distracted by our thoughts: did we lock the door? Are all the windows closed? Are we doing enough to keep the Sophies and Jeannes either happy enough or, barring that, safely locked outside?