It seems that Fellini’s Amarcord, a semi-autobiographical film inspired by the director’s childhood in and around Rimini, is a tremendously easy film to like. Critic Vincent Canby called it “Fellini’s most marvelous film” and “extravagantly funny”, while Roger Ebert described it as “a movie made entirely out of nostalgia and joy”.

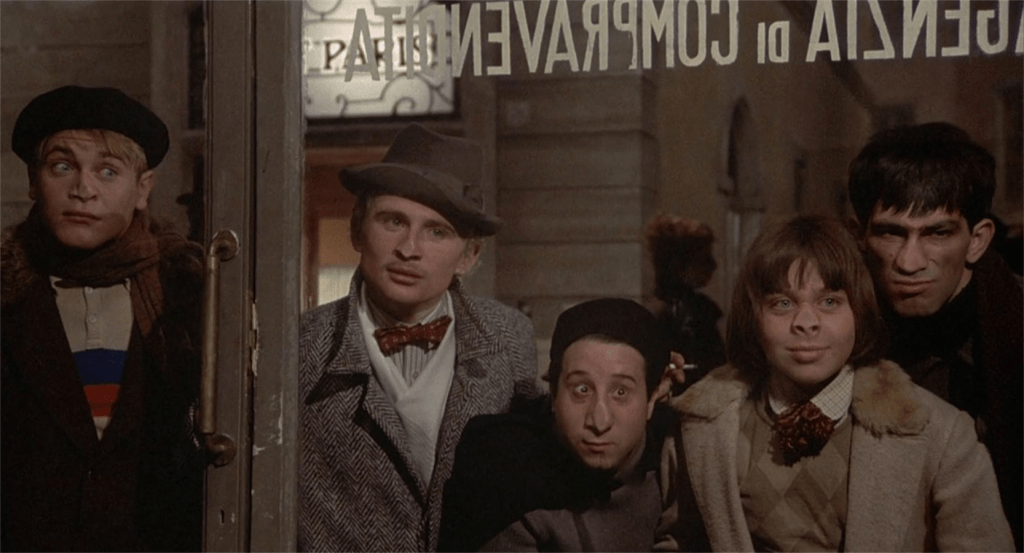

Me, though? More than halfway into Amarcord, I would have said that I’m not a fan at all. I didn’t find it funny or joyous. One of the tropes I’m more than a little tired of is: boys will be boys – and as a result I would’ve gladly thrown all of these guys below under a car.

By the time I arrived at the end of the film, my opinion had changed – somewhat, at least. But the first half of Amarcord was an hour spent mostly with a bunch of feckless manchildren of various ages and sizes, whose adolescent irreverence read to me not as joyous but as a mix of entitlement, sexism and bullying. And for all his nostalgic fondness of this particular time and place, I don’t think Fellini would have disagreed altogether.

As in Roma or indeed in I Vitelloni, to which Amarcord almost plays like a prequel, there is definitely more than a little nostalgia in the story Fellini tells, even (or especially) when the material is crass and vulgar. Fellini likes to depict his male characters in various stages of arrested development, he revels in their fixation on women’s bodies (and booties), in masturbation and crude pranks. These characters are jokes, but they are his kind of joke – and the women, although they are almost always stronger, more formidable and entirely too much for the men to handle, whether physically or emotionally, nonetheless humour them and let them get away with it. Boys will be boys. There are no more roles like the ones Giulietta Masina played in Fellini’s earlier movies: there hasn’t been one of those parts, the mature, long-suffering, abandoned woman bearing her partner’s multitude of sins with a mix of saintlike strength and fatalistic resignation, since Juliet of the Spirits.

However, more than in any of Fellini’s other films, the director draws a line from this society’s “perpetual provincialism and infantilism” (as Sam Rohdie puts it in his essay for Criterion) to the ease with which it falls for Mussolini’s fascism. Certainly, there’s an anti-authoritarian impulse in the juvenile antics of Titta (a character based on one of Fellini’s childhood friends, played by Bruno Zanin) and his gang of teenage hooligans – but it is only ever a step or two away from the might-makes-right bullying of the fascists, whose gaudy spectacle the townspeople are shown to adore as long as they’re not at the receiving end of the fascists’ wrath. Amarcord begins with the arrival of spring in Borgo San Giuliano, a village near Rimini, and this is celebrated by a traditional bonfire on which the effigy of a witch is ritually burned – but there is a meanness to the pranks the townspeople play on each other, such as when they take away the ladder while an old man is still on top of the pile of wood that’s started to burn. And by the end of bonfire night, it is difficult not to be reminded of other fires burning in Europe throughout the 1930s. The people that Fellini remembers from his childhood and adolescence aren’t evil, but they are largely thoughtless and careless and easily distracted, whether it is by large, curvy female bottoms, fast cars, or uniformed men parading through town. Give them half a chance and they’ll join in the tacky pageantry that the fascists were so fond of.

As Amarcord goes on, though, the film turns towards ideas and images that give a different slant to the farce and sex comedy of its first hour. There is a beautiful, dreamlike sequence where Titta’s brother leaves the family home to find the entire town shrouded in a thick mist, during which the film veers almost into something fairy tale-like – and it fits with the childhood memoir that Amarcord is to a large extent: everything in childhood and adolescence was more intense, the fogs were the foggiest ever. Another scene has most of the townspeople take small boats out to sea at night, expecting the arrival of a majestic ocean liner. The event, when it comes, has the lyrical artifice that Fellini has been working towards since his more naturalistic early films, and although the ocean liner passes in less than a minute, it seems to be the most beautiful, momentous event any of these people have ever witnessed. It is both a reflection and a refutation of the gaudy, ridiculous spectacle of the fascist parade earlier in the film: a display of beauty that is not about self-aggrandisement but rather about the delight of being dwarfed by a wondrous world.

Finally, even the adolescents are (almost) redeemed when they stop pestering the women of their town. In a scene late in the film they meet up at the Grand Hotel that has been shuttered (for the off-season or forever?), about which so many stories (largely made up) have circulated, and they lovingly, if somewhat clumsily, mime out what they imagine an elegant soirée there to have looked like. For once their reveries are not about sex but rather about what is as yet unattainable to them: beauty and romance and something other than the crude, provincial smallness that defines their every day – and they close their eyes and dance.

2 thoughts on “Forever Fellini: Amarcord (1973)”