Was The Elephant Man (1980), David Lynch’s follow-up to his first feature Eraserhead, my first Lynch? I’m not sure: it’s possible that I saw Twin Peaks first, at least the first half or so of the series, in a German dub, or perhaps I caught Blue Velvet on television late one night. It is even possible that I watched Eraserhead first and am repressing that traumatic memory. But The Elephant Man is often brought up as a good way to get started on Lynch: it tells a fairly straight-forward story, one that is based (albeit loosely) on the life of Joseph Merrick, a man suffering from severe deformities who lived in late 19th century London. You can see what would have drawn Lynch to the material, but the resulting film does not have the expressedly avant-garde edge of Eraserhead or of many of his later works. Aside from The Straight Story, it’s probably the film by Lynch that I would recommend first to people who haven’t seen anything else by him, unless I knew that they were into surrealist art.

But does that make The Elephant Man less Lynch, somehow?

I rewatched The Elephant Man a couple of weeks ago, after David Lynch’s death in mid-January. I’d not seen the film in decades; in fact, the last thing by Lynch I’d seen was the third season of Twin Peaks (sometimes referred to as Twin Peaks: The Return). I could have imagined watching more typical Lynch fare, the ominous, nightmarish surrealism of Mulholland Drive, or even Blue Velvet, which was shown on various channels to mark the sad occasion, but something drew me to his second feature instead. And it is certainly true that much of the film looks and feels more traditional than much of what Lynch created. Nonetheless, it doesn’t take long for the film to reveal the hand of its creator: The Elephant Man begins and ends with scenes that are easily recognised as Lynch – which, it needs to be said, is entirely different from the clunky imitations and parodies of the director’s style that usually miss the point entirely by focusing on the mere surface.

Looking at the imagery of The Elephant Man‘s first scene, it’s easy to see hints of Lynch’s later works: Laura Palmer’s suffering and death, slowed down into an unearthly cry, or even the Guild Navigator of his much-maligned Dune floating in space. The film’s final scenes too recall Fire Walk With Me, but also, again, Dune and its dream-like floating-head exposition dump, as well as the metaphysical strangeness of Lynch’s 2017 return to Twin Peaks.

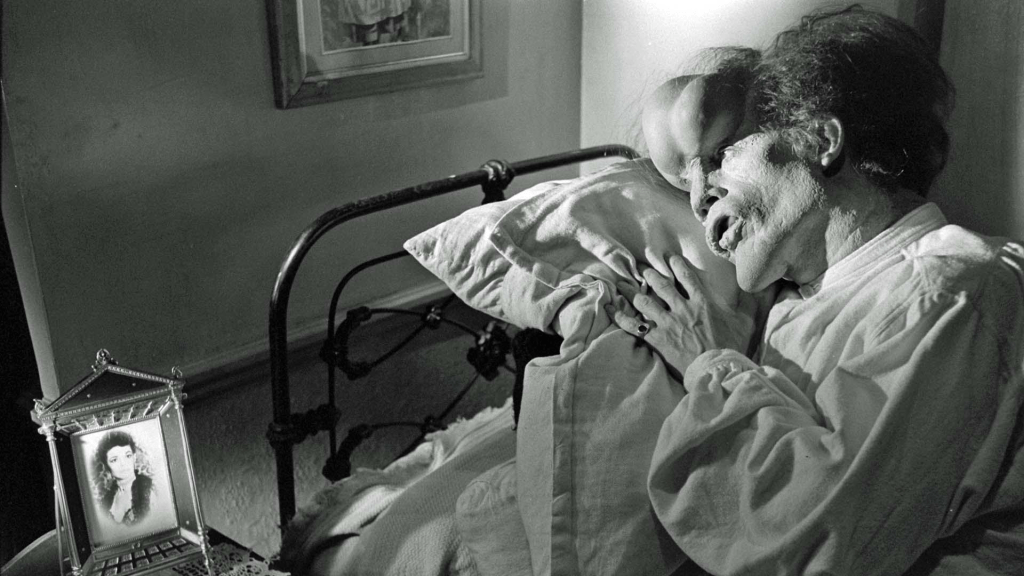

And while Lynch’s handling of the plot of The Elephant Man shows a formal and stylistic restraint that can seem untypical for the director, there are plot-less scenes throughout the film, ominous glimpses of late Victorian industrialised London, accompanied by a deep, unsettling rumble. There is something at work just underneath the surface, a machinery that grinds up humanity, feeding on suffering and toil. While these moments can be read as impressions of the London of the era, they are connected to the rest of Lynch’s work by creeping tendrils: they seem to belong in the same world as the ghostly apparitions, the woodsmen (“Gotta light?”) of Twin Peaks and the man behind Winkie’s, that haunt the director’s films. And similarly, the ethereal apparition of John Merrick’s mother in the final moments of The Elephant Man seems to be a manifestation of the same benevolent energy as Fire Walk With Me‘s angel or Wild at Heart‘s Glinda: figures that should feel corny and trite to an enlightened 21st century audience, but that in their strangeness are infused with a earnestness that Lynch was able to carry off just as effectively as the corruption and darkness that he and his art were often reduced to during his life.

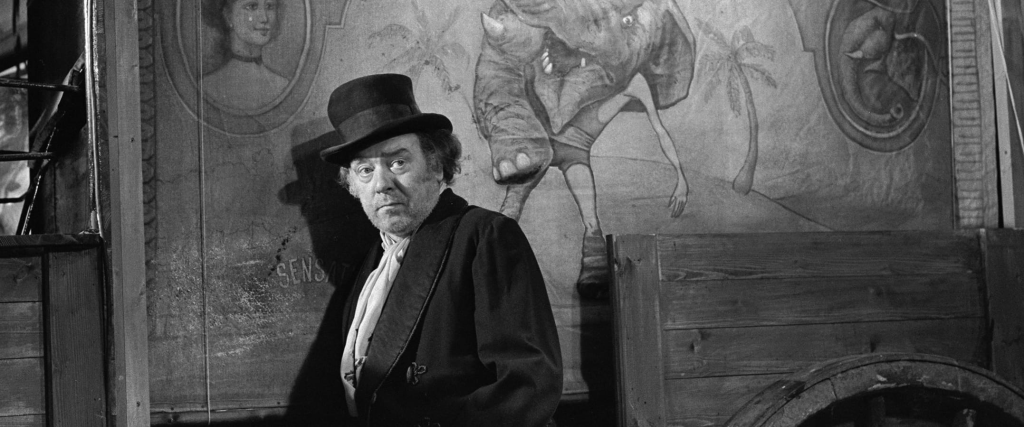

Verdict: Even if you were to focus only on the aspects of The Elephant Man that aren’t as recognisably Lynch, there’s a lot to like about the film. It is beautiful to look and has a wonderful set of performances, obviously starting with John Hurt’s John Merrick (even buried under these prosthetics, the vulnerability of the character is palpable) and Anthony Hopkins’ Frederick Treves, who comes to realise that his medical interest in taking on Merrick as a case may not be fundamentally different from the treatment Merrick received at the freak show where he found the man. The smaller roles are also cast perfectly, e.g. John Gielgud who infuses the hospital’s governor Carr Gomm with a wonderful curiosity and warmth. Perhaps my favourite performance in the film is that of Freddie Jones: as Merrick’s cruel keeper, he is arguably one of the villains of the piece, but he infuses his character with a corrupted melancholy that makes him infinitely more interesting than he could have been.

But it would be a mistake to take the Lynch out of The Elephant Man. The film blends its various facets more consistently than may be apparent at first: the underlying metaphysical dread infuses Merrick’s story as much as the cosmic benevolence of its final scenes. Merrick is as much a part of the strangeness of this world as he is affected by it. The Elephant Man may make for an easier introduction to Lynch than, say, Lost Highway or Mulholland Drive (though these can still be great starting points for anyone who clicks with Lynch’s darker and more ominous elements), but from here it’s not such a long distance to other works of his. (Arguably, it might be more jarring to start with The Straight Story and go to one of Lynch’s more surrealist films from there, though The Straight Story does have a Lynchian vibe already due to its Angelo Badalamenti soundtrack.)

But regardless of whether anyone wants to watch The Elephant Man for itself or because of its director, it is a film well worth revisiting, a striking, moody film that offers many pleasures and that feels more vital than so many nostalgic period pieces. Its elegy to the outsiders and outcasts is as poignant as ever. And if it serves as a gateway to the director’s other films, all the better.

One thought on “Criterion Corner: The Elephant Man (#1051)”