Giacomo Casanova: a man of many talents (allegedly). Check out his Wikipedia entry – which he would have probably loved doing! – and you’ll find that he “was, by vocation and avocation, a lawyer, clergyman, military officer, violinist, con man, pimp, gourmand, dancer, businessman, diplomat, spy, politician, medic, mathematician, social philosopher, cabalist, playwright, and writer”. (Wikipedia’s “citation needed” never seemed more apt.)

Yet, ask anyone what they know about Casanova, and they’ll tell you one thing: he was the lady’s man, a playboy extraordinaire, a big hit between the sheets. No one remembers the diplomacy, the philosophy, the writing. He might as well have been little more than a walking phallus, a sex toy with aristocratic aspirations.

In Fellini’s Casanova, the man himself feels slighted by this. He wants to be recognised for his brain as much as for what’s between his legs. Sure, you may think, first-world problems: are we supposed to feel sorry for a man who is considered the greatest lover of all time, because that is all he’s recognised for? But Fellini’s Casanova, who is a perfect caricature of common male insecurities, doesn’t really help his case: sure, he objects to being seen only as the sexual “adventurer” (we watched the German dub (more on that below), where Casanova is frequently described thus) and not the intellectual powerhouse he sees himself at. But dangle a sexual slight in front of him – say, that a mere carriage driver may be a more able lover than him! – and he is the first to pull off his trousers and demand a woman to prove his superiority, regardless of whether that woman wants to be bedded by him or not. After all, he is Casanova – how could a woman not want to feel his magic touch?

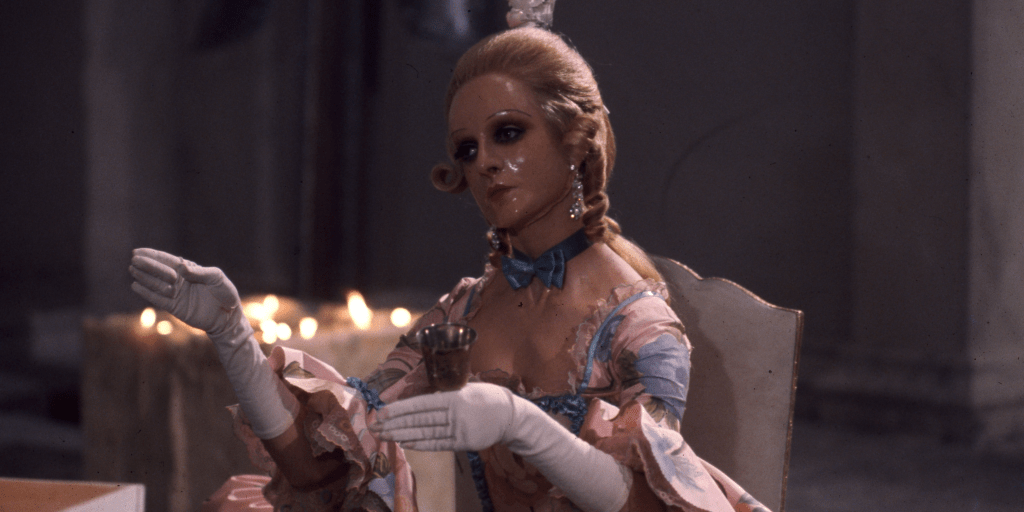

Fellini does something interesting with the material that only becomes apparent over time: Casanova is perhaps his most sexually explicit film to date, and at first it looks very much like a sex comedy, a series of scenes dedicated to farcial rumpy-pumpy in gaudy costumes – but it’s difficult not to notice how much the sex is drained both of eroticism and indeed of fun. Casanova’s erotic endeavours are depicted as ridiculous to begin with (his early encounter with a frisky nun for the pleasure of a rich aristocratic voyeur almost plays like a bawdy parody of a workout video – one, two, one, two, change position! -, albeit in stylised historical garbs), and the scenes become more pathetic, and more bitter, as the story progresses.

Fellini had a well-documented dislike for the character of Casanova, and his film certainly doesn’t hold back. His Casanova is grotesque and self-serving, he is a whining, pathetic figure when he’s not bedding a woman, and he’s self-serving to the point of being oblivious of his partners when he is engaged in sexual activity. The character is constantly desperate to prove himself, and the film is eager not to let him: it may depict his stamina and dexterity between (and outside) the sheets, but his love-making is usually compulsive and even mechanical. And yet, as played by Donald Sutherland (a choice that may seem odd, but that proves to be one of the film’s greatest strengths), Casanova also develops genuine pathos, especially in the latter parts of the film. He is never less than spiritually bankrupt, but by the end Fellini shows him as an old, sad man, and especially the final scenes are not without an element of understanding and even affection. The director may have disliked the character, but at times his Casanova recalls an older, less charming version of La Dolce Vita‘s Marcello Rubini or 8½‘s Guido Anselmi, two characters that are stand-ins for the director himself. He is someone whose ego has steamrolled any moral consideration for others, and he is slowly starting to realise how much this has isolated him. But whether this parallel is intended or not, Fellini definitely doesn’t go easy on Casanova: the film is frank about his deficiencies as a lover and a human being, and although there are enough sex scenes that show the recipients of Casanova’s sexual prowess to be willing partners, even ones that seem to enjoy the sex more than Casanova does, there are other scenes that show him as a serial abuser and rapist with no interest in consent whatsoever. (The sexual contest against the carriage driver has the woman he chooses as the recipient of his sexual skills voice her unwillingness, but neither Casanova nor his audience care to hear her pleas, as they are irrelevant to the audience’s enjoyment or Casanova’s need to prove himself.)

Sadly, Fellini’s Casanova isn’t a part of Criterion’s Essential Fellini box set (we recorded it off television, and I decided to include it in this series of posts), most likely due to rights issues. The version I saw was adequate, but the film would deserve a top-notch remaster. Both structurally and visually, it is perhaps most reminiscent of Satyricon in its episodic depiction of a past that always prioritises the Felliniesque over the historical. It is aesthetically rich to the point of almost overwhelming its audience, and it often has a striking artifice in its production design that is never pretty but often beautiful: the film starts with a phantasmagorical carnival in Venice that sees a gigantic god’s head sink beneath the waves (echoes of the enormous bust of Mussolini the townspeople venerate in Amarcord), and continues with a boat trip across a stormy sea that obviously consists of sheets of plastic and that nonetheless get across the sense of the storm more expressively than most footage of an actual storm would. These scenes set the stage for a film that is a visual (albeit gaudy) feast throughout. It comes as no surprise that cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno, who had previously collaborated with Fellini on Satyricon, Roma and Amarcord, also filmed Visconti’s The Leopard, Fosse’s All that Jazz, Altman’s Popeye and Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen: all films that do not depict a specific reality so much as they create it.

Like many of Fellini’s films beyond his black-and-white period, I am ambivalent about Fellini’s Casanova. I don’t always feel keen to spend much time in his world, which is often loud and crass and gaudy, and I do admit to rolling my eyes at most of Casanova’s sexual adventures as much as at his insistent self-pity. But Fellini’s criticism of the character and his notion of masculinity, and the richness of the world he and his collaborators depict, and the absolute commitment Sutherland brings to depicting this grotesque, pathetic, old man, infusing him with pathos but never letting him off the hook, make this aesthetically rich, bleakly satirical sex (anti-)comedy well worth seeking out in addition to the films included in the Criterion box set.

2 thoughts on “Forever Fellini: Fellini’s Casanova (1976)”