It’s a conundrum: this late in Criterion’s Essential Fellini box set, I didn’t expect to find a film I’d like as much as And the Ship Sails On – but at the same time, I ended up finding it more frustrating than many of the films I liked considerably less. There is a lot I love about And the Ship Sails On – but it feels like by the time Fellini made it, he had mellowed with age, and in this case I wish he hadn’t. The film is too loving and mild as satire, when the themes it addresses would have required a sharper sensitivity, one that isn’t averse to drawing blood… and this shortcoming is much more obvious in 2025 than in 1983.

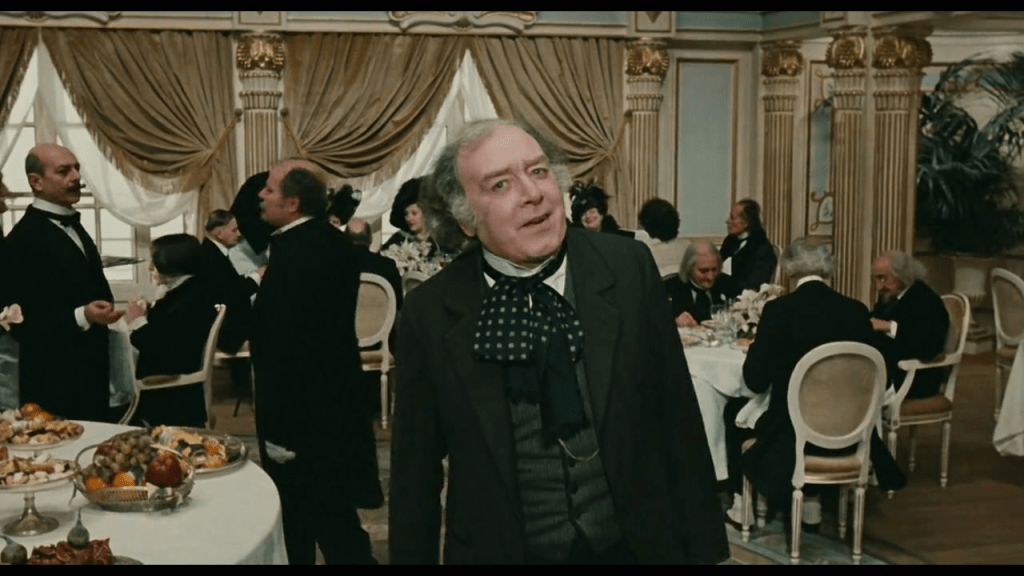

First things first, though. In And the Ship Sailed On, Fellini tells the tale of a cruise in memory of a late opera star, Edmea Tetua, whose ashes are to be scattered near the island where she was born. The rich, cultured passengers, many of them involved in the arts themselves, are clearly devotees of La Tetua, but the trip also affords them with the opportunity to put themselves on stage: much as with the classical poetic form of the elegy, their expressions of mourning are always also performances of their own talents. What’s the point of remembrance if you can’t make others remember you as well? What is a memorial ceremony other than yet another show? The story is narrated by Orlando, a journalist who recalls the town historian in Amarcord: as portrayed by Freddie Jones (an unexpected but entirely fitting addition to the Felliniverse), he is a bumbling but endearing figure, something of a joke that nonetheless draws affection – definitely more so than the pampered, preening singers, conductors, producers and actors that make for most of the ship’s passengers.

This cast of characters is a good fit for the film’s style. In Fellini’s filmography, there’s a clear move from a relatively naturalist (or neorealist?) aesthetic to something more stylised and theatrical. The artifice is there in individual scenes in his earlier films, but at the latest with Juliet of the Spirits it becomes the director’s predominant mode, as Fellini and his collaborators foreground the theatrical aspect more and more. The films are no less cinematic for all of this, certainly, but Fellini is more than happy to help himself from the bag of tricks of the stage. This contributes to a self-contained quality that the films have: where in La Strada or Nights of Cabiria there’s a sense that there’s the entire world just off-screen, this changes drastically in his later works – if you walked off camera, chances are you’d bump into a proscenium arch, or into the lighting crew, or the sound engineer’s desk. There is a scene late in And the Ship Sails On that literalises this, where we suddenly see the movie crew at work, though fascinatingly, this doesn’t so much have the effect of making the film, with its models and miniatures and contraptions, feel any less real: instead, it ends up making the two frames, the film and its story and the making of the film, seem equally real. There’s a camera filming the camera filming the film we’re watching, it’s frames within frames within frames. There is no meta when everything is fiction, story and artifice. We’re all of a piece with the theatre, and the difference between characters, cast and crew, between onstage and offstage, is negligible. Either we’re all real or none of us are and we’re all just characters in a story.

However, it’s not just the foregrounded artifice and fourth-wall breaks that make Fellini’s later films and especially And the Ship Sails On theatrical: he very much uses the forms and genre of the stage, though always blending them with the cinematic. The film begins with silent black-and-white footage of the launch of an early 20th century steamer, with all the signs and trappings of early motion pictures: the jerky frame rate, the softness of the footage. The characters on screen also behave like people not yet used to the ubiquitous camera, and especially the extras glance at the camera, point it out to others, pull faces, break the illusion that a camera merely depicts neutrally what is already there. Sound only fades in shortly before the upper-class passengers, dressed up for the occasion, board the Gloria N. – and what incidental dialogue there is soon gives way to an operatic tune, as the passengers set the scene in song. And the Ship Sails On isn’t an opera throughout, but music and song are almost as frequent as dialogue, and it is almost a shame that Fellini didn’t decide to stick exclusively with the operatic format, an artistic form whose artifice and larger-than-life expressiveness clearly suits him – as much as its latent, over-the-top ridiculousness does.

This stage-like stylisation of the film finds echoes in other filmmakers, and it is one association in particular that I could not shake throughout: And the Ship Sails On is probably the film by Fellini that most prefigures Wes Anderson, frequently making me think of Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel in particular. There are many similarities, both thematic and stylistic, in how the two directors create a historical world that is entirely uninterested in realism, instead feeling more like the dream of a memory of a time lost to us now – though I suspect that Fellini might have found some of Anderson’s stylistic tics too finicky, too tightly controlled. Where Anderson’s films always have a touch of the architectural, Fellini is never not a circus ringmaster whose shows need to teeter on the edge of chaos, and if the elephants go on a rampage and the clowns start an impromptu pie fight while the diva’s neckline plunges lower and lower, all the better.

At the same time, And the Ship Sails On does have a political streak to go along with the operatic. This begins with its depiction an upstairs/downstairs dynamic on board the Gloria N.: we see the cruise ship’s mess hall staff and the firemen shovelling coal, and while the passengers are fascinated with them and even perform for them, there is a sense that these impromptu performances are about the performers more so than the audience: they’re another chance for the rich and cultured to show just how magnificent they are and how deserving of the applause of their lessers (and the adulation of their equals).

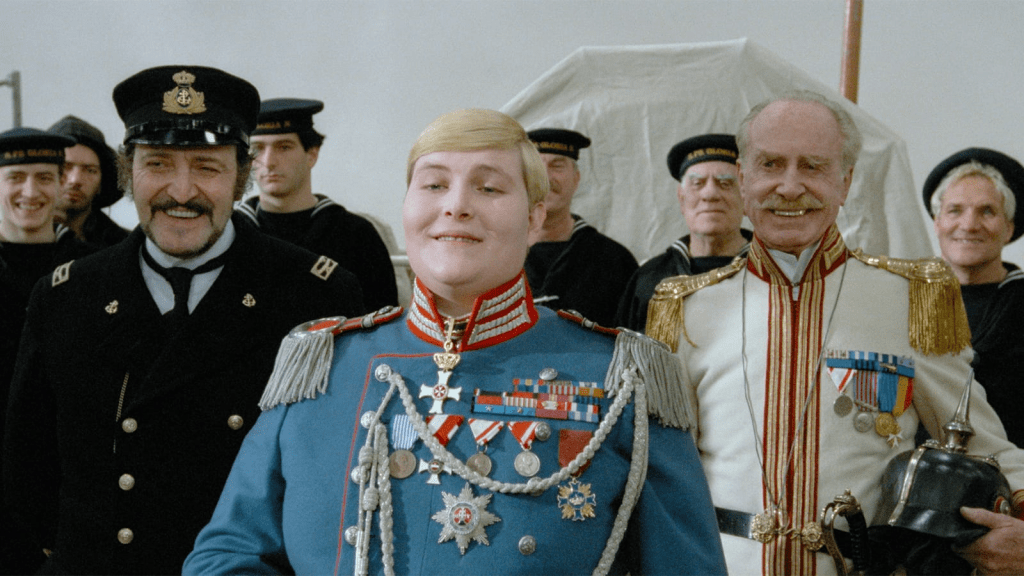

As the film goes on, it develops this motif of the haves and the have-nots further: And the Ship Sails On takes place at the onset of the Great War (albeit it’s an opera-appropriate stylised 1914), and halfway through the movie Serbian refugees, escaping the political unrest of the time, seek refuge aboard the Gloria N. and are accepted, very begrudgingly by many but more enthusiastically by others who appreciate the respite the Serbians offer from stuffy high culture and the even higher warbling notes of opera. That is, until an Austro-Hungarian warship arrives on the horizon and demands that the refugees, who are claimed to harbour terrorists, are turned over to them. (The military vessel, by the way, has a wonderfully plump, organic, cartoonishly evil aesthetic that in a better world would have inspired Terry Gilliam’s Sink the Bismarck.)

I’d loved And the Ship Sails On up until this point. I’d loved its gentle satire, poking fun at the ridiculous toffs and their self-involved ways, as much as I had loved the film’s nostalgia for an idea of a time much more than for the actual time itself. But once the refugees enter the scene, and the ship’s passengers are more and more clearly seen to be a microcosm of Europe, the movie’s gentleness started to become a problem for me. Perhaps this read differently in the early ’80s, when the film came out, but in 2025 the relatively mild anti-refugee sentiment of the passengers of the Gloria N., and the doomed resistance that they put up to the aggressors, seems too milquetoast. At a time when European refugee policies cause thousands of deaths in the Mediterranean each year, the nostalgic fantasia of Fellini’s Ship of Fools takes on a bitter aftertaste, because let’s be realistic: these people in their fancy clothes would have handed over the refugees to their certain death in a heartbeat. Some very willingly, others in a display of genteel guilt. These characters are the kind of people who would reserve their rebellion against autocracy and military might for the stage and the page.

Obviously I cannot blame Fellini for his 1983 film not addressing the dire treatment of refugees fifty years later, and the specificity of my issues with the film is unfair: while the question of how Europe deals with refugees isn’t a new one, it is the specifics of the crisis in the last decade or so that resonate with And the Ship Sails On in ways that don’t do the film any favours. Fellini can’t be faulted for not foreseeing the tragedy in the Mediterranean. Even then, though, I think that Fellini lets his upper-class characters get off too lightly. Our narrator Orlando himself hints at the unreliability of his narrative, so it’s possible to read a grimmer version of the story into its gaps: were the refugees actually handed over willingly or only under duress? It is possible that a grimmer, more honest version of the story can be found in between the lines. Even so, I do think that this film, one of Fellini’s last ones, would have been stronger if he had blended his nostalgic theatricality with some of the sharper, more bitter notes that are in evidence in his scathing take on Casanova, or even the stranger, nastier satire of La Dolce Vita. In 1983 and in 2025, he lets his version of Europe get off too lightly. The ship goes on exactly because its passengers look out for number one in the end.

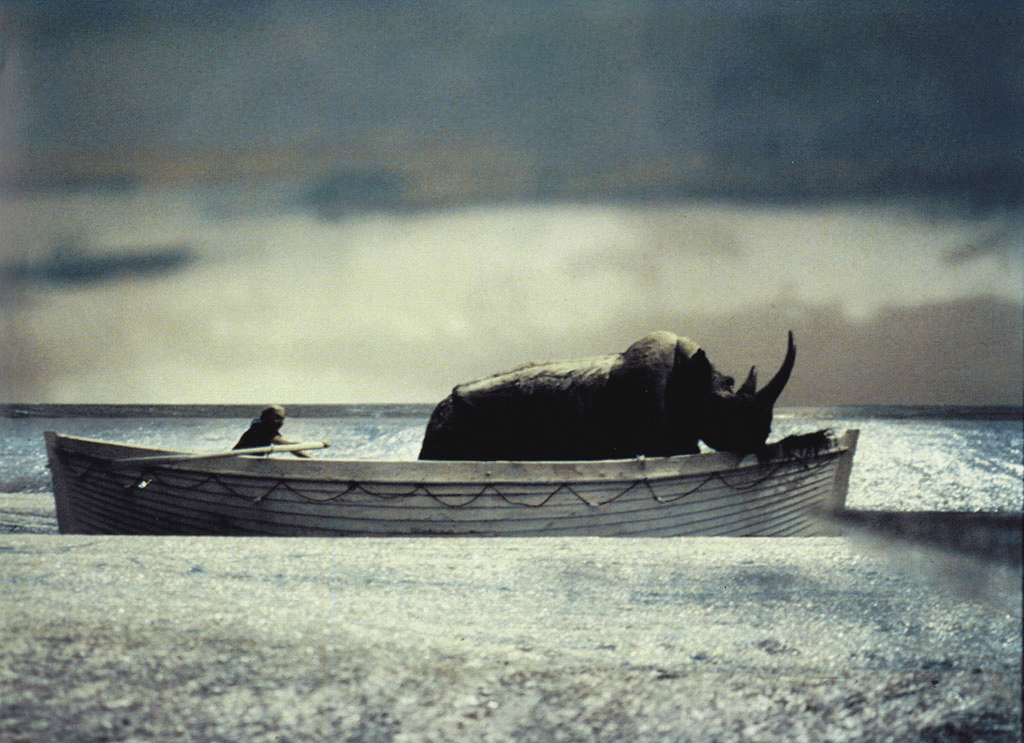

In the end, it seems to me that Fellini was too much in love with his theatrical, operatic depiction of the past to give it the kind of teeth that would have made it more relevant to the present (whether his own or ours). And I can definitely understand the appeal: I myself would be more keen to revisit And the Ship Sails On than, say, Satyricon. But since the film does aim at a degree of social criticism, I do rather wish that it had the more acerbic qualities of earlier films by the director, giving these elements more bite – and this in turn could have added more contrast and depth to the wistful, charming elements, the surreal images and the melancholy romance, that And the Ship Sails On evokes beautifully. As it is, perhaps the iconic rhinoceros’ horn is not nearly as pointed as it should be.

One thought on “Forever Fellini: And the Ship Sails On (1983)”