And there we are: the final film on Criterion’s Essential Fellini box set, Intervista. It’s not Fellini’s final film: the director would go on to make The Voice of the Moon, released in 1990 and starring Marmitey Italian comedian Roberto Benigni, but even if the decision not to include that one was down to rights issues, Intervista feels like the right end point, seeing how it is about filmmaking, memory and finding that decades have passed and all of a sudden you’re an old man.

Also, quite literally and more than any other film by the director, Intervista is about the man himself: Federico Fellini.

It’s easy to imagine some being frustrated with Intervista because of how navel-gazingly meta it is. In some ways it feels like, over the course of his career, Fellini refined the subject of his art until it was literally revealed to be Fellini himself – an assessment that isn’t quite fair, but neither is it entirely inaccurate. With each of his films, he stripped away more of the incidental matter, so it only makes sense that, by the time Intervista comes along, what is left is a monument to the life and work of the director, wrapped in an ode to Cinecittà, the legendary studio where he made his movies. One strand of Intervista is about Fellini in pre-production while being interviewed by the Japanese, another is a memory – or a movie? for Fellini, is there a difference? – of his first visit to Cinecittà in 1938, a third strand is the director making an adaptation of Kafka’s Amerika at Cinecittà in the present, and it all adds up to the film that is Intervista – which translates as “interview”, so arguably we’re watching a conversation that Fellini is having with himself.

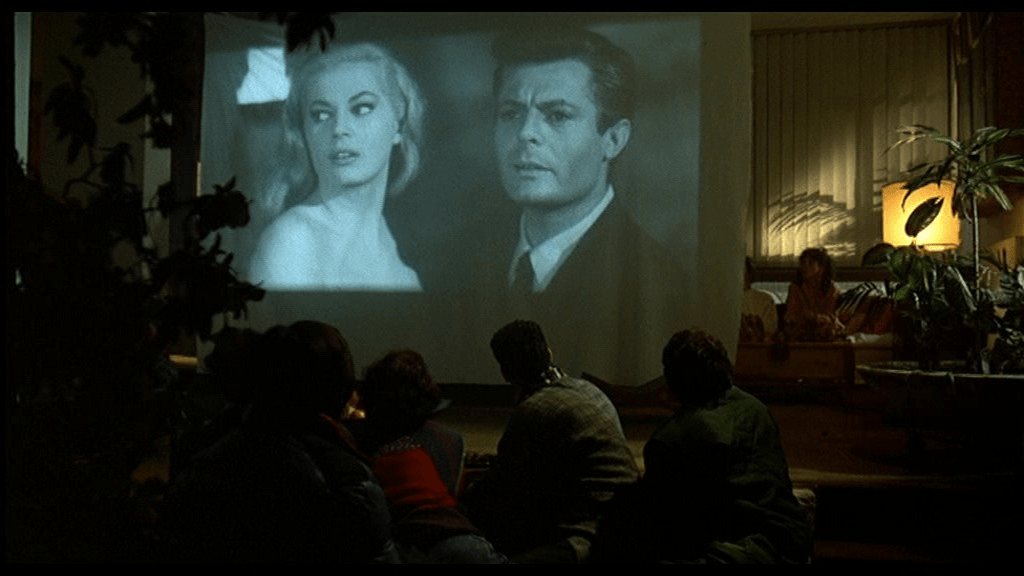

But while Fellini is in every cell of this big heap of meta, he is also oddly absent: more than before, we focus on the cast and crew as cast and crew, we see collaborators working on sets and backdrops, looking for extras on the streets and in the subway, we watch the hairdressers and makeup artists. Or are they actors depicting the crew? Meanwhile, the actors playing characters in one or another of the story strands also play themselves, in front of and behind the camera. For all the film’s tendencies towards metafictional self-involvement, it feels generous in letting others take a bow. And this is nowhere as apparent as in the scenes in which an aged Marcello Mastroianni, dressed for a TV commercial as Mandrake the Magician, accompanies Fellini to Anita Ekberg’s mansion, where the two actors – older, heavier, so much less glamorous – meet for the first time since La Dolce Vita. Together with their guests, made up of Fellini’s entourage and the Japanese TV crew (whose director offers to cure Mastroianni of his nicotine addiction), they watch the iconic Trevi Fountain scene projected onto a bedsheet. And the moment is magical, conflating time and films, letting us see Mastroianni and Ekberg as their older and younger selves. Watching these two icons watching who they once were on a makeshift cinema screen could feel narcissistic, but Fellini and his actors make it work. I can only imagine how the scene must have hit for the people who saw both La Dolce Vita and Intervista when they originally came out, seeing and feeling the time that has passed in those faces on the screen, wrinkled and worn and smooth and fresh at the same time. It’s an almost lethal dose of nostalgia, but it goes far beyond a mere “Remember when”: the time that has passed practically becomes a palpable character in a scene that feels both melancholy and conciliatory.

Perhaps it is the framing story of a Japanese TV crew seeking to interview Fellini that prompts this thought: Intervista is what the director would concoct if he’d died and found himself in the hereafter of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s After Life. It is made up of the bits and pieces that have made up Fellini’s career, and at the same time it reveals that act and craft of filmmaking in all its moth-eaten magic much like the amateur (in the truest sense of the word) artistry of the counsellor-filmmakers in Kore-eda’s fog-shrouded waystation where the dead choose the memory that they will leave behind for eternity. Intervista is an encapsulation of Fellini’s work and his life, made in the only form that makes sense: cinema.

Though, if this film is the memory that Fellini leaves behind, there is one notable gap in this memory: Giulietta Masina, his companion and collaborator for decades. Seeing how much Intervista refers – sometimes obliquely, sometimes overtly – to the director’s filmography, it would be interesting to hear from someone more knowledgeable about Fellini whether she was ever supposed to be in Intervista, and whether she makes herself felt in other ways. Sadly, Ginger and Fred, which the director made in between And the Ship Sails On and Intervista and the only film co-starring Masina and Mastroianni, isn’t a part of the Criterion box set – and it isn’t widely available, let alone in a recent release. However, I am hoping to get my hands on the DVD, which would allow me to write an epilogue to this series, focusing on Fellini’s last collaboration with his wife and the star of many of his earlier films. Fingers crossed!