When you think of Gene Hackman and neo-noir, what comes to mind? For most people – including me -, the answer is simple: The Conversation. And obviously there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that choice: Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 film is unarguably one of the best, most iconic paranoia thrillers of the 1970s and a great showcase of Hackman’s talents. But sometimes a film’s reputation can be so enormous, it eclipses other films that are also deserving of recognition.

Arguably, Night Moves (1975) is one of those films.

Comparing the film to The Conversation, Night Moves is perhaps not as instantly recognisable as one for the ages. This is a much smaller, less overtly ambitious thriller. Directed by Arthur Penn (whose Bonnie and Clyde and Little Big Man probably did their fair share of eclipsing Night Moves as well) and written by Alan Sharp, at a first glance it looks and feels more TV-sized than Coppola’s classic. On the surface, there’s a workmanlike quality to the film that is amiable but deceptive: even if you’re just looking for 1970s neo-noir starring Gene Hackman, and even if you were to conveniently forget about The Conversation, there’s William Friedkin’s The French Connection (and possibly its John Frankenheimer-directed sequel), right?

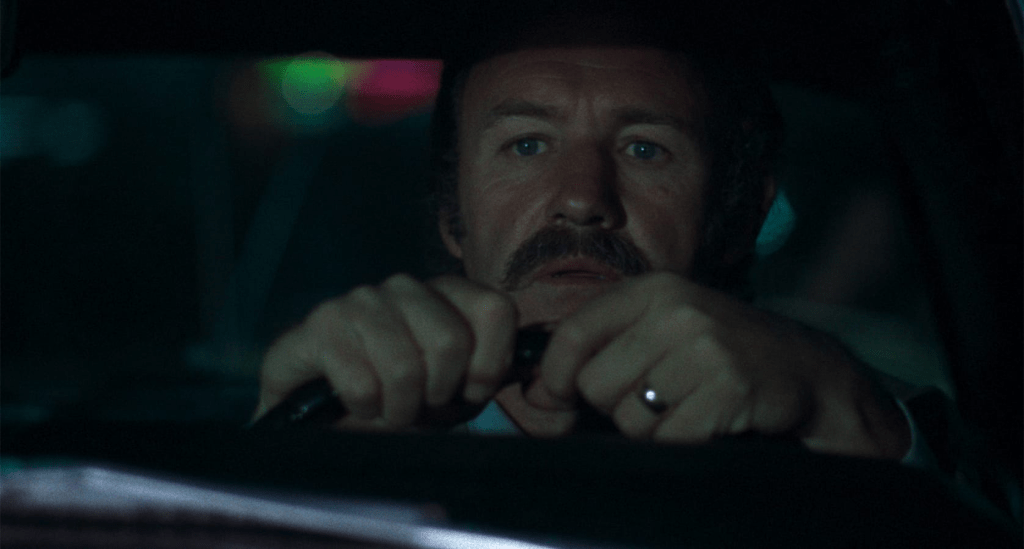

Night Moves isn’t the kind of film that immediately impresses – and in this, it mirrors its protagonist. Harry Moseby (played by Hackman), a small-time private investigator, used to be a pro football player, but these days the closest he tends to get to a game is watching it on a small TV, and when his wife asks who’s winning, he answers: “Nobody. One side is just losing slower than the other.” Ironically, the same can be said about his marriage: while there is still affection between Harry and his wife Ellen (Susan Clark), she is tired of this defeated sad sack who is primarily good at a job that is even more sad than he is, consisting mostly of seedy little cases of infidelity.

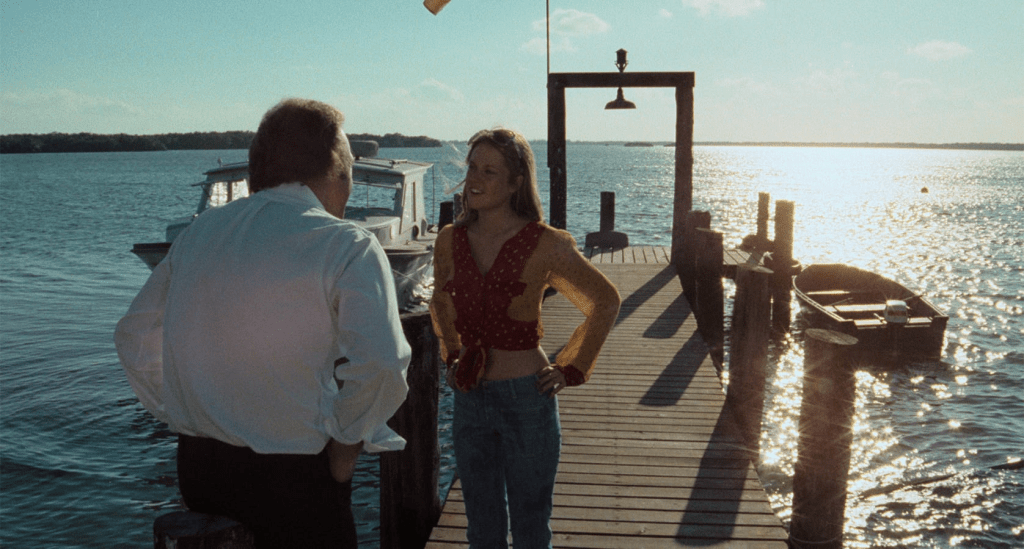

When Harry finds out (not through investigation but accidentally, to add insult to injury) that his wife is having an affair, he throws himself into his latest case as a way of escaping his depressing life, at least temporarily. An aging actress hires him to find and bring back home her sixteen-year-old daughter Delly (Melanie Griffith). And this is where, looking at what it says on the label, you’d expect this neo-noir thriller to turn into something dark and labyrinthine, corruption hiding just underneath the sunny Los Angeles surface, right? Not quite. Following the obvious clues, Harry soon finds out that Delly is most likely hiding away at her stepfather Tom’s place, down in the Florida Keys, and in his situation he is more than happy to leave behind his wife and his life for a couple of days.

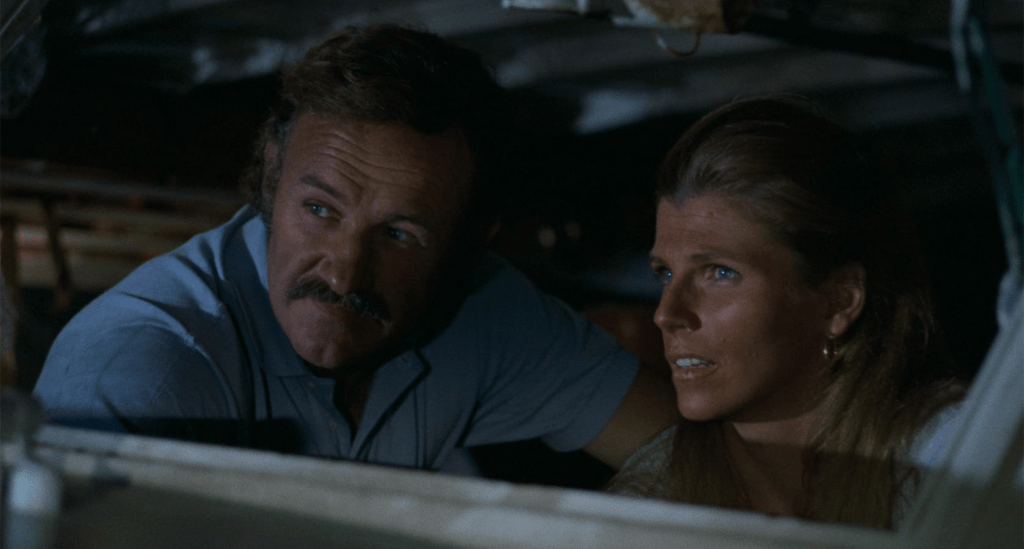

It is when Harry finds Delly that I first started to wonder: if this is a thriller, why does Harry find the missing teenager roughly half an hour into the film? And where’s the thriller part of it all? Night Moves lulls its viewers into a false sense of security, because for the longest time it doesn’t seem to be a thriller at all but rather a drama about a sad detective with a failing marriage – so, obviously, he wouldn’t be averse to a little distraction offered by Paula (Jennifer Warren), the girlfriend of Tom (John Crawford)? There are occasional hints of darker things going on, but for much of the time they play as non-sequiturs, indications of a world in which bigger, and worse, things are happening elsewhere. For much of Night Moves‘ running time, there doesn’t even seem to be much of a case for our investigator to investigate. But then the thriller plot kicks in, and it adds another dimension to Harry’s struggles: his work can be an escape, but it is also how he attempts to regain control of his life, by doing what he does well. Except, sometimes, that is not enough.

Verdict: Gene Hackman is the perfect casting for the likes of Harry Moseby: even more than ’70s mainstay Roy Scheider (who co-starred with Hackman in The French Connection), he’s never been the kind of leading man who is immediately noticeable due to superstar looks. Where the likes of Robert Redford and Paul Newman, or relative newcomers such as Al Pacino, were overtly handsome, Hackman was always a bit of a schlub. He was the kind of guy that was not a fantasy: the kind of man audiences wanted to be or be with. He was relatable, but at the same time he had an intensity that was unmatched and that made him perfect for the neo-noir protagonist. Hackman was a lead looking like an everyman.

Night Moves makes great use of this, lulling us into a sense of security: this is not the kind of guy who gets drawn into the big, epic, life-and-death case, right? And the film doesn’t present us with the kind of deep-rooted corruption and evil that powered a neo-noir classic such as Chinatown (released just a year earlier), not do we get the topical, cinematic paranoia of The Conversation. Instead, there’s something just as sad-sack to the crimes Moseby finally uncovers. Tonally, Night Moves makes for a good companion piece with Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, and there are even whole sequences that feel like more humdrum, everyday echoes of that film (especially Moseby’s time-out in Florida), but where Philip Marlowe, the anti-hero of Altman’s more satirical neo-noir, finally embraces the glib cynicism of the times with his constant mantra “It’s okay with me” (it isn’t, really), Moseby is made vulnerable by his underlying sense of guilt and his wish to do what’s right. Late in the film, it becomes apparent that his chosen profession is not a squalid little escape from his own life: he may have been making most of his money taking photos of adulterers, but when he does see a chance to right a wrong, he will jump at it, no matter the cost.

And this is where Night Moves embraces its genre fully – because there is always a cost.