I think it’s fair to say that, after Wes Anderson has directed 11 feature films (12 if you count The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Three More, which Wikipedia does), I am something of a fan – and yet, I don’t really think of myself as such. Of his last eight films, starting with Fantastic Mr. Fox (check here for a typically wonderful Six Damn Fine Degrees by Julie about the film), I’ve loved several and enjoyed the others a lot. Admittedly, I have some issues with the early films of his I’ve seen – Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic -, but after a streak of eight movies that I like or even love, shouldn’t I be able to say that I like the work of Wes Anderson? And, if not, why?

In part, I guess it’s that I bounced off the films of his that I saw first, and to some extent that first impression hasn’t quite dissipated. Of course I can see the craftsmanship that was already in evidence in The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic, but in those films I found Anderson’s style offputting, the artifice distracting me from whatever was going on in emotional terms. Both of these films have a key moment where tragedy cuts through the archness – or at least it’s supposed to, but I distinctly remember sitting there and not buying it. The films were doing their damnedest to make me feel something, but the break in style felt forced to me. Perhaps it’s just that I first had to learn how to watch Anderson before I could really enjoy him, but a recentish revisit of The Life Aquatic still left me cold, though probably less so because by then I was more fluent in Andersonese. (One of these days I will rewatch The Royal Tenenbaums, and I hope I’ll enjoy it more than the first two times I saw it.)

But I don’t think it’s just my first experiences with Anderson that make me resist the idea that I may be a fan of the director. The third film by Wes Anderson that I saw was Fantastic Mr. Fox, and the circumstances under which I saw it were less than ideal: on a flight, watching the movie on the tiny screen of the in-flight entertainment system. Considering how lovingly, intricately crafted each frame is in an Anderson film, and doubly so in this, his first stop-motion animation, you’d think that the effect is largely lost when you’re watching on a sad excuse for a screen, using bad headphones, while around you the bustle of a long-distance flight is going on. But no: I loved the film, more than I’d ever loved watching anything on a flight, and later repeat viewings just confirmed my feelings. Fantastic Mr. Fox is funny, witty, beautifully crafted – and, strangely, while its animated world is more consistently artificial than those of earlier Anderson films, I found myself engaged much more on an emotional level. At first I suspected that this was because I could accept Anderson’s artifice better in the more overtly artificial world of animation, but a dozen or so films later I think it’s something else. Many of the later non-animated films by Anderson are as obsessed with creating their own little doll’s-house worlds – but the director has found ways of staying within this artifice while investing his characters with emotional heft. Where The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic break with the usual Anderson style when they want to hit emotionally, the sentiment in the later films is intertwined with the artifice that makes the director’s style so recognisable. In comparison, I remember myself almost resenting the big emotional scene in The Royal Tenenbaums, while recognising its effectiveness: there was something too obviously manipulative about the cinematography and editing, and especially about the use of music. To me, it felt like the film was nudging me: watch closely, this is the sad part. You may cry now. (I didn’t.)

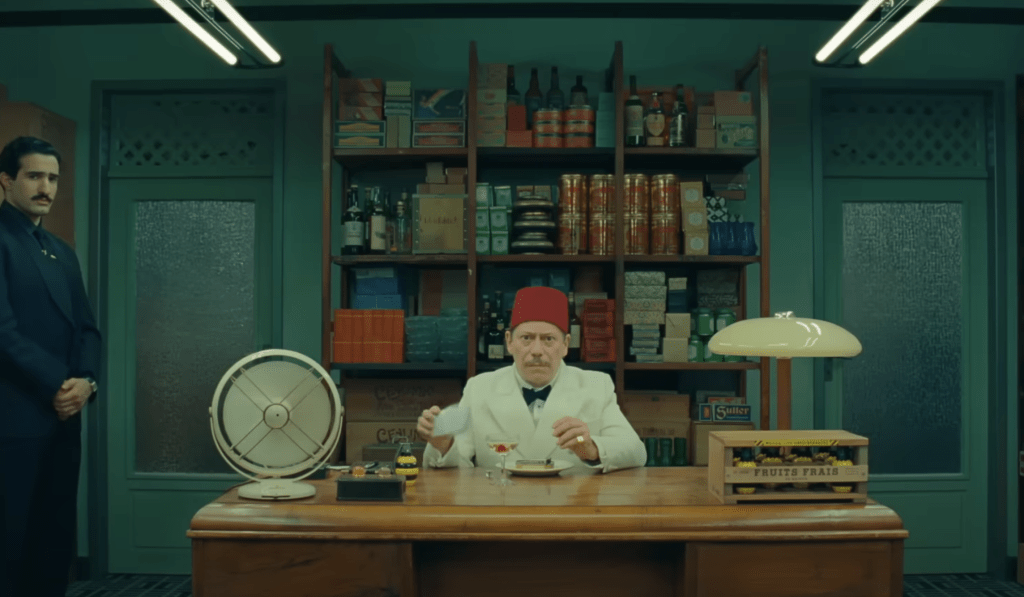

Finally, one of the things that keeps me from admitting that I may be a Wes Anderson fan is that I find myself nodding along to the frequent accusation that he’s basically making the same film over and over again. Same actors, same shots, same deadpan delivery, same musical style. Here’s some symmetry, here’s a snap zoom, here’s a miniature shot. There’s Bill Murray exuding Bill Murrayness, there’s Willem Dafoe playing a villain or weirdo, and look over there, that’s Frances McDormand, Edward Norton and Tilda Swinton. There is an extent to which I watch each new trailer for a Wes Anderson film thinking: that’s it. We’ve reached Peak Anderson. That’s also very much what I thought when I saw the trailers for Asteroid City and The Phoenician Scheme, Anderson’s last two films released at the cinema. And I can see why: the trailers play like a collection of Greatest Hits, like Anderson supercuts. Quirky characters standing in planimetric compositions, looking out at the audience, delivering their lines in a deadpan tone. (At times, Wes Anderson’s films can feel like Warner Brothers cartoons as made by Yorgos Lanthimos.)

I do think that is a fair assessment of the trailers advertising the latest Wes Anderson film. However, I also think that they do the films themselves a disservice, because when I actually watch them, they don’t feel like they’re all the same movie, just with different plots and settings used as window dressing. Obviously I’m not saying that the films are wildly different – but then, why should they be? You go to see a Wes Anderson film, you expect to see a Wes Anderson film. But Asteroid City, with its themes of grief, love and art, has a different feel from the neocolonialist parody – is it critique? is it nostalgic? both, perhaps? – of The Phoenician Scheme. The Grand Budapest‘s melancholy tale of the rise of fascism is not the same as the outcast teenagers’ romance of Moonrise Kingdom or the family dramedy mixed with cartoon hijinks of Fantastic Mr. Fox. With Anderson, it’s like eating at a restaurant with a strong signature style: obviously the dishes are all recognisable, not least because they are so perfectly assembled that we barely want to take a bite, but there is still a striking range of flavours.

Which also explains why in most discussions of the films of Wes Anderson, I found that while everyone would agree that there are few directors who have as recognisable a style as him, everyone not only has different favourites but also different films that they dislike – which would be odd if Anderson indeed made the same film over and over again. And, fascinatingly, while many of the people I’ve talked to about the films of Wes Anderson online would point at one or two of them and say that this or that one didn’t do anything for them because it’s basically Anderson on autopilot (or, worse, akin to a kind of WesGPT, trained on all of the director’s films), there will be others who say the same thing about one of the other films while defending the one that others consider to be generic Anderson. Even though the director’s work is instantly recognisable and, to be fair, more similar in style and aesthetic than the films of many other filmmakers, Anderson doesn’t keep making the same film – and watching them, rather than just looking at the stills and checking out the trailers, reveals the variation that there is. The world of Wes Anderson may be instantly recognisable – but there are many different worlds contained in it. Even if, in a display of convergent evolution, they all may tend towards planimetric composition.