If anyone had told me a few years ago that not only would a Star Wars story open itself up to comparisons with the likes of Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows, it would bear up to these comparisons, I would have dismissed it as hyperbolic fanboy self-importance. Star Wars is Star Wars, a pop-culture blend of samurai film, westerns, war movies and sci-fi serials. Does it need to make itself look important? Relevant? Is that the measure of its worth?

Now, after Andor has run its course, I’m a convert. Not only can Star Wars be about something: it can do so while remaining essentially Star Wars.

I was already on board when the first season of Andor came out in 2022 – and I was open to it being something more than just a prequel series. Its creator, Tony Gilroy, had shown that he’s a smart, savvy writer and filmmaker with the Bourne films, which were better than a pulp series of Robert Ludlum adaptations had any right to be, and doubly so with Michael Clayton, a legal thriller that showed Gilroy’s abilities of taking a genre seriously and unlocking its potential in the process. However, I did not expect this: a story deeply rooted in Star Wars that makes its Galactic Empire into something other than operetta fascists, bad guys at the intersection of old Hollywood Nazis and fairytale antagonists. I did not expect the story to go the places it did, touching on the hypocrisies of a prison system that serves the military-industrial complex, or on the corrosive nature of spycraft, or on men and women pushed by the ever-tightening screw of authoritarianism into throwing bricks, throwing punches, throwing themselves at the flunkies of fascism, fully aware of the possible cost – and measuring success not in big, bombastic victories, but in a series of minute, almost imperceptible wins in the face of oppression.

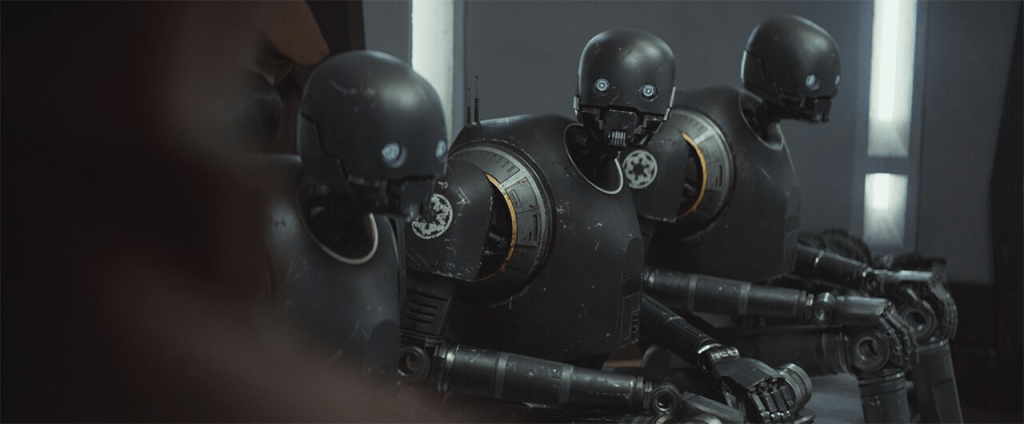

I also did not expect a series that would allow its antagonists to be comprehensible, competent, and always entirely human – and nonetheless the purveyors of an evil that, in the end, cares not about competence or loyalty or anything other than its own benefit and advancement. Ironically, in many ways, Andor‘s Empire reminded me not only of the actual, real-world Nazis at times, but of other empires closer to home: the faces we’re used to seeing on screen as the good guys. Forget the cartoonish Emperor of Star Wars‘ original trilogy: the representatives of the Empire in Andor are first and foremost bureaucrats, so much in love with their idea of order that it becomes easy to see it as being worth any price – provided that price is paid by others. By workers, prisoners, or those smelly, underdeveloped people living on some backward planet.

What makes Andor work is in no small way that it takes the material it was working on seriously, though not the way fans do, turning pop culture into holy writ. Gilroy and his creative team looked at how this world, and especially this society, would work. How would the Empire exert pressure, on whom, to what end? Where would control be most vital? Who would be at the receiving end – and where would that suffering, that constant pressure, find outlets in revolt and rebellion?

It is ironic that Andor feels so vitally of its time – this may be a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, but it relates so much to the world we live in, especially over the last couple of years – because Gilroy did not set out to tell a story about present-day politics. If anything, he looked back at human history, and at historical rebellion: against colonialists and fascists, against authoritarianism. We clearly see the French Resistance in the citizens of Ghor trying to stand up against the occupiers, but we also see pretty much any native peoples being tossed aside and destroyed because they’re in the way of narrowly-defined progress and success, measured first and foremost in control. Perhaps best of all, none of these echoes to human history feel like simple set-dressing: the story works as Star Wars and as allegory, both of the past and the present.

Andor is likely to end up my favourite series of 2025, but it is not perfect: the restrictions of streaming television are felt at times. Some of its stories suffer from stop-and-go pacing, and some characters and story strands would have benefited from having more time dedicated to them. It is also hampered in its final episodes by having a clearly defined end point in Rogue One, though there is also a joy in seeing how well Gilroy & Co manage to make Andor segue into the film it serves as a prequel to. (Rogue One, in turn, suffers from the comparison: after Andor, it feels too slight, its characters too flimsy, its tone too frivolous and its story too generically that of the wartime action adventure, when before Andor the film was generally, and favourably, held up as ‘the dark and gritty one’. Also, its sometimes blatant fan service rankles more in comparison to a series that does not feel beholden to an increasingly toxic fan base.)

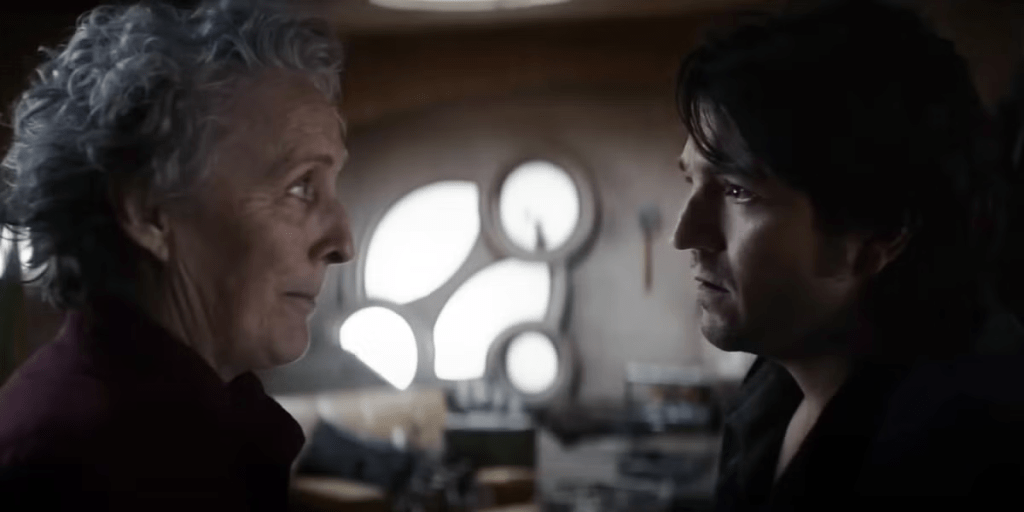

But in spite of my structural quibbles, Andor shows how vital Star Wars can be if done with intelligence and integrity. There are so many scenes in Andor that will stay with me, and differently so from the iconic setpieces of classic Star Wars: Mon Mothma (a beautifully subtle performance by Mon Mothma) dancing herself into a frenzy to forget that she’s just sealed the fate of her childhood friend; Maarva Andor (Fiona Shaw is always good, but she gives Maarva a weary warmth and anger that needs to be seen) speaking as a hologram to the people mourning her, telling them what must be done; Luthen (Stellan Skarsgård), carving off piece after piece of his soul, and Kleya (Elizabeth Dulau), his adoptive daughter, saveguarding what remains; the people of Ghor, one by one, starting to sing their anthem, while their end has already been decided elsewhere and the executors are only waiting for the order.

And its smaller, more personal moments: poor, doomed Syril (Kyle Soller) realising the extent to which he has made himself a willing, and oh so useful, idiot to the Empire, and Dedra (Denise Gough) finding that her loyalty to fascism means nothing at all once she’s no longer deemed useful – or both of them standing up to Syril’s monstrous mother (Kathryn Hunter has so much fun with a role that is both cartoonish and terribly real), and us wishing that they could also stand up to the evil they’ve made such an integral part of their lives. Or just Andor (Diego Luna, who gives the character a soulful hauntedness that he was only able to hint at in Rogue One) bearing witness to fascism in its many forms on the one hand and the many acts of insurrection, some random, some not, that put one crack after another in the brittle construct that is the Empire.