Do you remember a time when you were a child, and there was something you really, really wanted? So much so that nothing else mattered? How far did you go to get it?

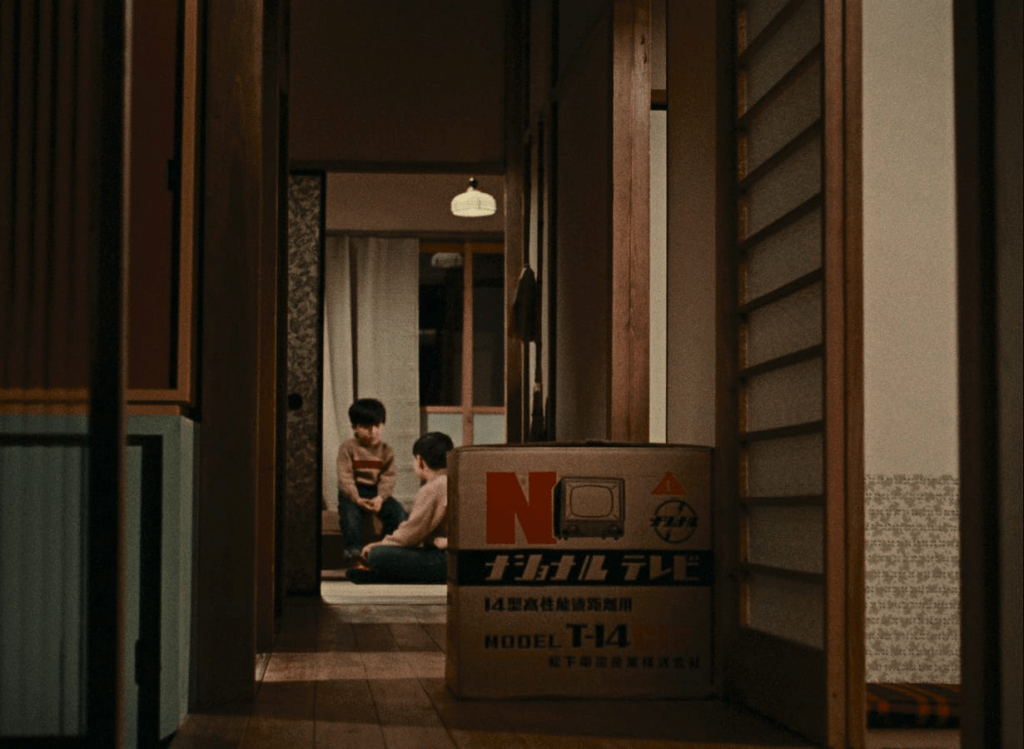

In Yasujiro Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), Minoru (Koji Shitara), a kid growing up in suburban Tokyo, wants nothing more than a television at home. Sure, he and his friends can watch sumo wrestling at the house of the neighbour couple who’s hip and modern and permissive (and, it needs to be noted, don’t have any kids of their own), but they are bohemians, and there are rumours in the neighbourhood that the wife works as a singer at a cabaret, which Minoru’s conservative parents can’t abide: how can these people be anything but a bad influence on the children? So, not only does the Hayashi family not get a television, Minoru’s parents forbid him to visit next door, he doesn’t even get to benefit from neighbours who aren’t still stuck in the pre-television past.

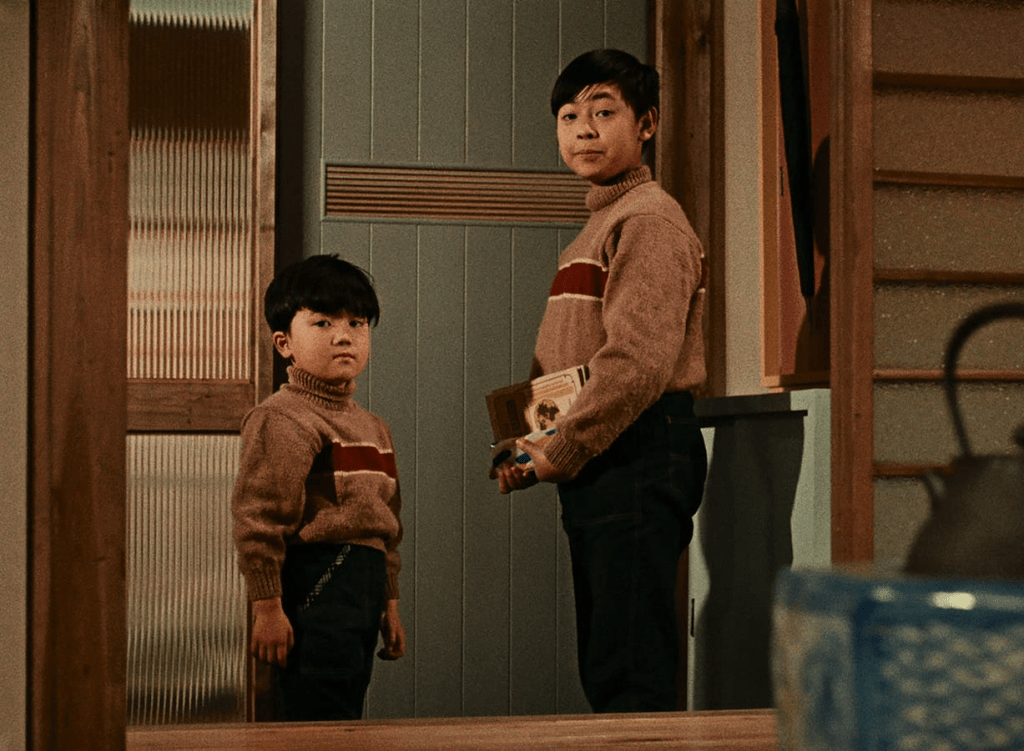

So Minoru does the thing that seems most obvious to a kid: he throws a tantrum. In fact, he throws the tantrum to end all tantrums, which gets his father to intervene: he tells Minoru and his kid brother Isamu (Masahiko Shimazu), whose primary mode of behaviour is to imitate (and, in the process, parody) his older sibling that they should keep quiet – which pushes Minoru over the edge: in an angry fit, he tells his parents that this is all grown-ups do, talk incessantly, exchanging pointless niceties (such as ohayo, the Japanese word for “Good morning” and the film’s original title), without ever saying what they really mean. After they are sent to their room in punishment, Minoru and Isamu decide to get serious in their crusade against all adults: they go on a silence strike, determined not to exchange any words with anyone else. They even talk to each other only when it is absolutely necessary (with the two of them having vastly different ideas as to what constitutes ‘absolutely necessary’). Meanwhile, the adults, being typically oblivious of what goes on in their children’s minds, don’t get why Minoru and Isamu are suddenly snubbing everyone – which makes this whole silence strike somewhat less effective than is intended.

Verdict: Good Morning was my first ever Ozu film. I’d heard so much about the director, his thoughtful lyricism, the fabled ‘pillow shots’ (brief, non-narrative shots of empty space or mundane objects, “visual commas” that create a pause in the film and subtly comment on its themes), his influence on directors ranging from Jim Jarmusch and Wim Wenders to Kelly Reichardt and Hirokazu Koreeda. And of course I went, albeit unwittingly, for the film by Ozu that begins and ends (apart from featuring them throughout) with young boys farting. Yes, that’s right: one of Good Morning‘s recurring plot points is Minoru and his friends, on the way to and from school, playing a game: press a boy’s forehead to see if he can fart on command. (One unfortunate member of this group of friends finds that his straining to fart has unfortunate side effects, though arguably it is the boy’s mother who bears the brunt of this misfortune.) Take that, arthouse cinema.

Though don’t let the flatulent schoolboys fool you: while Good Morning is a affectionate if not a little mischievous portrait of a Japanese childhood in suburban Tokyo a decade after the war, it is also, and mostly, a satirical ribbing of postwar middle-class society and of Japanese social mores. The Hayashi family and their neighbours are at the beginning of a postwar wave of consumerism, in which, more and more, the topics of conversation are the products of the era: televisions, washing machines and the like. Oh, and gossip about those neighbours who aren’t around at the moment: while the men in the neighbourhood are at work, the women complain about snubs and slights that are amplified into grand insults that can result in someone being ostracised for a simple misunderstanding – or because their son is giving all the other adults the silent treatment, which must obviously be the fault of the parents! Meanwhile, when the men return from work, they get drunk in a local bar and bemoan their lives (and complain about the brain-rotting properties of those new-fangled television sets), leaving their wives alone with all the domestic work.

So, did I like my first Ozu? I did: it is a charming film that offers insight into a society that I’ve not seen much of. While I’ve seen my fair share of Japanese films, these were generally about modern Japanese society, they were historical films, or they featured gargantuan lizards threatening to destroy Tokyo. (Precious little farting in those latter ones, though that Godzilla dude does seem to have a mean case of halitosis!) The closest I’ve seen to Good Morning in terms of the era would probably be Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, though the suburb where Minoru hankers after a TV set is very different from the geographic divide between the rich and poor parts of town that Kurosawa’s thriller straddles. The film finds an effective balance between the cultural specifics of the time and place it depicts and its more universal elements: the escapades of Minoru, Isamu and friends are not far removed from stories such as René Goscinny’s Le Petit Nicolas stories and many other gently ironic tales of childhood in which, in the eyes of the kids, everything takes on a significance and a sense of drama – and in which the rules that the children follow reflect and parody the often equally ridiculous structures of the adult world.

Though, fair warning: if you are no big fan of pre-teens throwing loud, long tantrums, beware, even if there is fun to be had in little tyke Isamu reflecting his brother’s behaviour back at him with a solemnity that unwittingly mocks Minoru’s childishness. But if you can forgive Minoru a child’s sense of entitlement, especially in the face of grown-ups that may be better at sticking to social conventions but who are sometimes no less childlike in their wants and needs, do check out Good Morning: come for the (surprisingly sweet) fart jokes, stay for the social satire. Even if