Most people, when asked to think about spy movies, will think of James Bond, of Sean Connery or Roger Moore or Daniel Craig. They’ll think of shootouts and stealth and suave secret agents bedding exotic beauties.

The novels of John Le Carré, inspired and informed by Le Carré’s own work for both MI5 and MI6 in the mid-20th century, are as far from James Bond as one could imagine – though it is just about possible to bend them into something more Bond-like in the name of entertainment, as happened for instance with the TV adaptation of The Night Manager that was released in 2015. As written, Le Carré’s stories are often less thrillers, though they can be thrilling, than tragedies, infused with existentialism, paranoia and a Kafkaesque sense of inevitability. And these are rarely as much in evidence as they are in Martin Ritt’s 1965 adaptation of The Spy Who Came In from the Cold.

The plot of The Spy Who Came In from the Cold is both complicated and simple. On one level, it’s a complex tangle of subterfuge, half-truths, and even the occasional truth placed just so in order for the right people to interpret it as a falsehood. The jaded spy Alec Leamas (Richard Burton), who was station chief of MI6’s West Berlin office, has lost his network of operatives and seen them killed, one by one. At the behest of the Service, he becomes the leading figure in a plot that begins with the other side, and in particular the East German Intelligence Service, coming to see him as a potential defector. The goal of all of this is to entrap one of Leamas’s Eastern counterparts and make him look like a traitor to his own Service.

Following this plot-within-a-plot takes considerable concentration: for at least half of the film’s running time, we’re following conversations between men used to wielding truth and lies as weapons, but less used to differentiating between them, except as a means to an end. As a result, we’re asked to try and understand these conversations on three different levels, at least: first, what is being said literally; secondly, what is hinted at between the lines, though perhaps unwittingly; and thirdly, the ends to which both the apparent truth and the implications and insinuations are employed. This mirrors Leamas himself: the spy is playing a version of himself that is bitter, cynical and an alcoholic, which is incidentally is a good description of the man, and then there is the real Leamas, the pretend Leamas who is only a hair’s breadth away from the actual man, and possibly even Richard Burton, who, by all accounts, shared several of Leamas’ qualities. At any moment, which Leamas are we seeing – and how real is the difference? At the same time, our protagonist is clearly functional enough an alcoholic to apply his not inconsiderable talents as a skilled surgeon might use a scalpel, but he is also savvy enough to know that, just maybe, his superior at MI6 (Control, a small but key part played with subtlety by Cyril Cusack) isn’t telling him everything. In the silences and omissions in the various stories and identities, suspician and paranoia fester – Leamas’, the East German intelligence officers’, and even our own.

Meanwhile, in parallel to this complex game of making others believe a story by telling everything but the story they’re supposed to believe, there is a much simpler, starker parallel story: the tragedy of Leamas and his lover Nan Perry (Claire Bloom, no stranger to tragic Cold War stories), who is pulled into the interwoven MI6/Stasi plot as a pawn. As so often in Le Carré’s stories, love proves to be an Achilles’ heel, the weak spot that opens people up to betrayal: it leaves the characters open both to being betrayed and, wittingly or not, betraying others. The Spy Who Came In from the Cold is no different in this respect: for all his jadedness and cynicism, Leamas falls for the idealistic Perry, who believes in a Communism that is far removed from the Cold War as it is fought by the intelligence agencies on both sides. And it is these feelings that make it possible for both of them to be used even more effectively, regardless of how much Leamas tries to keep Perry out of it – at a considerable price.

Verdict: In a conversation early in the film, Control tells Leamas: “Our work, as I understand it, is based on a single assumption: that the West is never going to be the aggressor. Thus, we do disagreeable things, but we’re defensive… I mean, occasionally, we have to do wicked things. Very wicked things, indeed. But, you can’t be less wicked than your enemies simply because your government’s policy is benevolent, can you?” The film version of The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, which makes some changes to the original novel but captures its heart perfectly, doesn’t argue that the two sides of the Cold War were really the same, but it does suggest that, once you get into the actual conflict, it doesn’t matter: the ideologies, the everyday realities of people on either side of the Iron Curtain, these may differ – but in the shadow world of espionage, and for everyone touched by it, the difference is irrelevant. Either side is willing to go as far as the other, even further, if it increases the chances of winning this war, Cold or not. And neither side will spare any thought to innocent bystanders. Very wicked things, indeed.

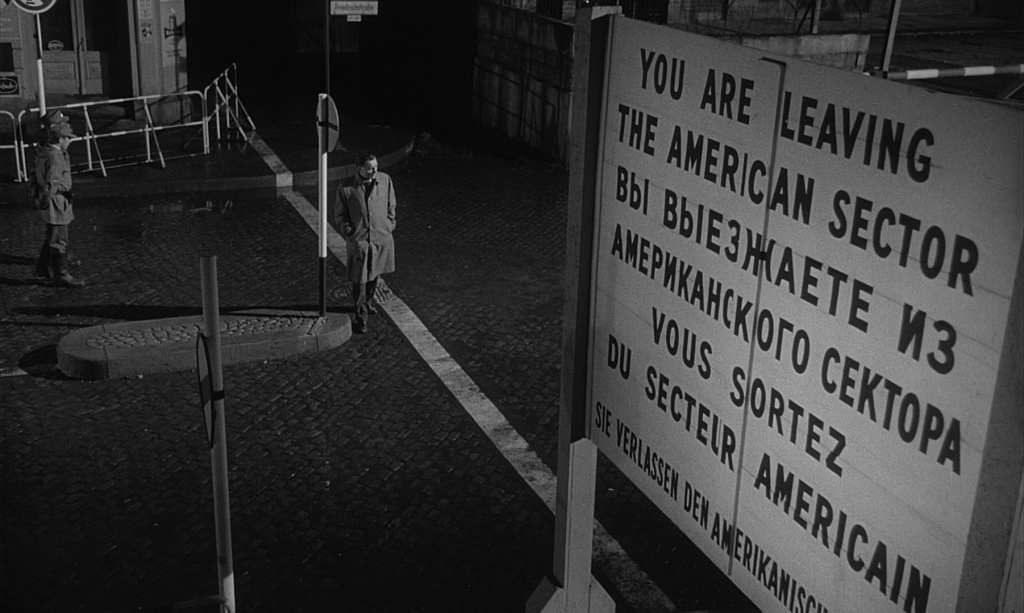

As in the best adaptations of Le Carré, The Spy Who Came In from the Cold depicts the corrosive nature of this world without giving in to a need to soften or romanticise it. This is what makes the film so strong, but also frustrating to audiences less interested in this bleak kind of fatalism: from the first plaintive note played on its soundtrack and the first starkly black-and-white shot of Checkpoint Charlie belying the murky dark greys of the intelligence world, we sense where this must necessarily go. Beliefs, ideals, feelings: these will not save the protagonists. The final fates of the characters aren’t heroic. This is a world that is deadly, not in the exciting sense of a spy thriller such as the ones inspired by a certain Mr Fleming: it kills not just the body but the soul.