Stop me if you’ve heard this one: Hollywood, the Dream Factory – it is actually quite silly, and none are more silly than Hollywood superstars. Drop them in the real world on their own, without their entourage, and they wouldn’t survive five minutes. They’re shallow, self-centred and vain, they barely have a personality of their own, which is probably why they choose acting in the first place. But then, they bring joy to all our lives, so all is forgiven. We love you, Hollywood superstar!

When I first saw the trailer for Jay Kelly, I was apprehensive, to say the least. I’ve enjoyed several of Noah Baumbach’s films, in particular Marriage Story. Also, even after almost 20 years of Nespresso ads, I like George Clooney, in films such as Michael Clayton that play against his superstar image as much as in those that make use of that very image, such as Ocean’s Eleven, or those that goof around with it (see Hail, Caesar!, for instance). Jay Kelly, though… I have to say, it looked bad. It looked like the kind of film Hollywood likes to make, using the thinnest veneer of satire at the expense of the inanities of Tinseltown to justify a lot of sentimentality. It looked, at best, like a homeopathic version of the kind of film Fellini made during his heyday, diluted until there was one part of critique to 999 parts of Hollywood patting itself on the back for the good job it is doing.

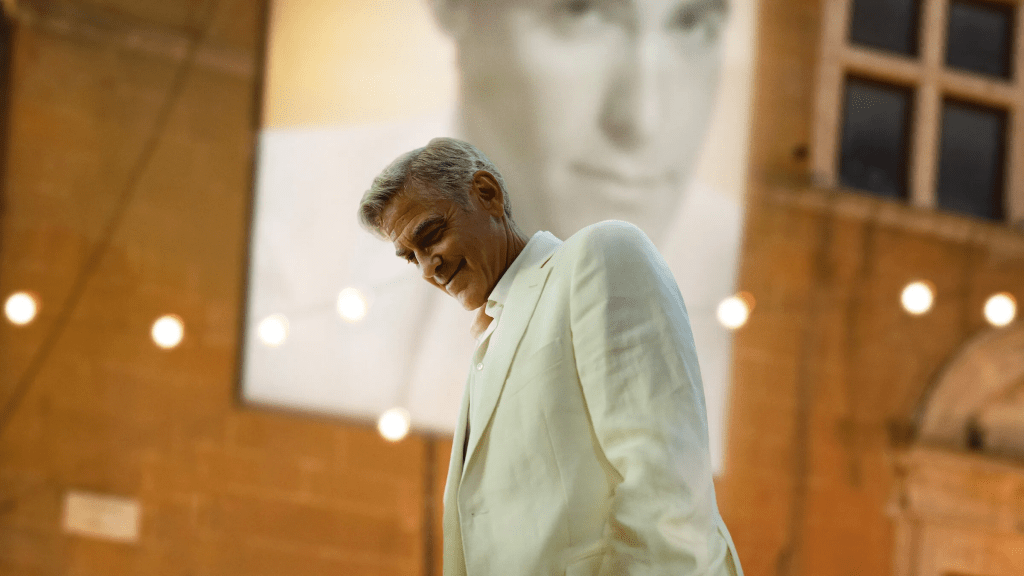

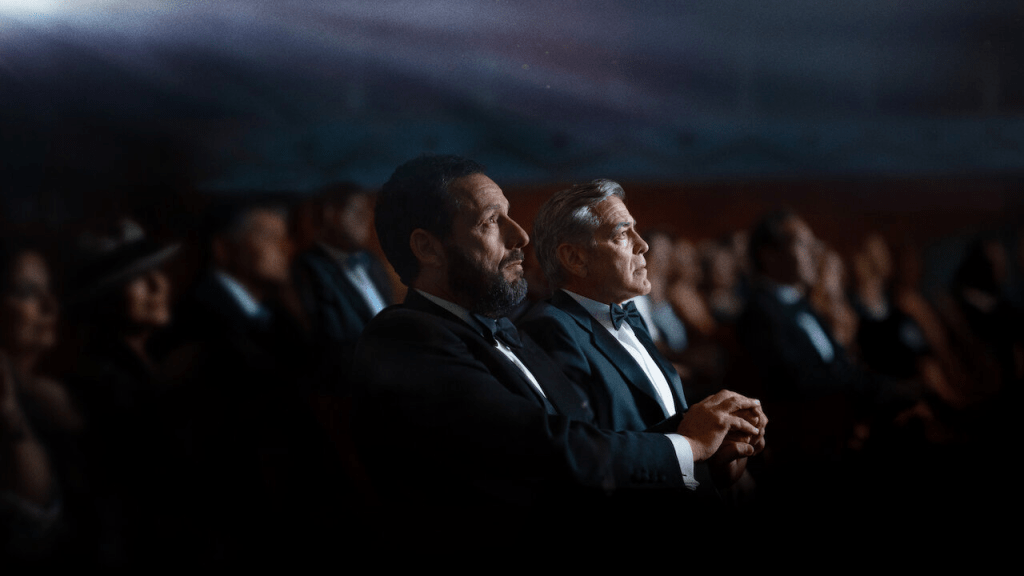

While the film itself does have more to offer than the trailer (not something that is always the case, sadly), that first impression of Jay Kelly was nonetheless not inaccurate. George Clooney plays a version of himself – G.C. and J.K. aren’t miles apart, after all – that is definitely satirical: while Jay is certainly charming and affable, he’s also a flimsy, shallow excuse of a man. He isn’t much of a presence in the life of his younger daughter Daisy (Grace Edwards), and his older daughter Jessica (Riley Keough) clearly considers him one of the main reasons why she’s in therapy. Few people outright hate Jay – apart from the friend from his younger days whose big role, and then girlfriend, he stole -, but the people who tell him that they love him, first and foremost his manager Ron (Adam Sandler), mainly seem to do so because, after all, if they didn’t love him it would make their own lives lived in service of the star tremendously sad.

When Peter Schneider (Jim Broadbent), the director who gave Jay his first big break and catapulted him into stardom, dies, it prompts the kind of soul-searching in our protagonist that is frequent in these films. Jay realises that, other than the career of a superstar, he has very little to show for his life, so he goes off in order to get the recognition he so desperately craves, from his family, fans and entourage. He travels to Europe, supposedly to accept a lifetime award he’d rejected up to now, but mostly to stalk Daisy who is taking some time out and travelling to Europe with her friends before college. Jay’s trip is largely played for comedy, as the star gets to travel to Italy on a second-class (just imagine! a Hollywood star travelling with the hoi polloi!) train carriage, surrounded by a quirky collection of largely adoring Jay Kelly fans – and it’s not just here that the film’s comedy veers towards the smarmy. It pokes fun at Jay being desperate to be reassured that he’s not just a star but also a real boy, and someone worthy of affection, but most of the people travelling with him are little more than one-dimensional clichés written and played for laughs.

Most of the characters that surround Jay remain one-dimensional, though the film gives him flashbacks and other emotional scenes that soften the already mild satirical edge. These scenes are designed to add substance to an insubstantial protagonist, adding a glibly sentimental dimension to the story, as the film’s star gets ample opportunities to break out the patented Clooney sadface. I’ve liked many of the actor’s more serious turns in films such as Michael Clayton, Solaris and Syriana, so this is not me saying, “Clooney, stay in your lane” – but in Jay Kelly, we get too many shots of distilled Clooney somewhere on the continuum between wistful and depressed that are simply unearned. Since the film plays these with more conviction than it does its satire, the satirical shots at Jay come across as half-hearted, even dishonest, which in turn renders the melancholy ones maudlin and self-serving. Jay Kelly, it seems, is trying to sell us Jay’s failures as a parent, friend and human being less as critique than as reasons to feel sorry for him, rather than for the people that surround him and that have to compensate for his inability to be good at anything else than being a star.

I can imagine a version of Jay Kelly that puts conviction behind its satire, that is sharp and honest in its critique of the protagonist, before it shows us the flipside and makes us feel some sympathy for a man made up of little more than shiny surfaces. I can also imagine a more knowing film that plays with the readily available meta level: Jay is a movie star, of course he knows how to play his audience. The film itself could be his increasingly desperate attempt to make us love him, and its mild satire could be part of this manipulation: look at me, I can laugh at myself! Doesn’t that make me more loveable? But no: the Jay Kelly we get doesn’t really do clever. It is committed to making us feel sympathy for the superstar, rendering its satire half-hearted at best.

It’s where the film focuses not on its title character but on his entourage, especially on Adam Sandler’s manager and Laura Dern’s publicist Liz that it best manages to shake its self-serving sentimentality. Again, I can imagine a different film: one that focuses more on the people whose lives consist of orbiting Jay than on Jay himself. But that’s not what Jay Kelly does, and the few, tantalising scenes that are about pretty much anyone other than Jay just end up being frustrating, showing glimpses of another film that is then withheld. But perhaps that is the problem: I find it easier to imagine the kind of film Jay Kelly could have been – something sharper, more perceptive, more satirical, something that isn’t designed to make us feel the sadness of a tremendously privileged person who feels sorrow at his own inadequacy. A film that doesn’t use the self-pity of its protagonist to ask, first and foremost, our forgiveness. But that film obviously needed someone else to make it: perhaps Armando “The Thick of It” Iannucci or Jesse Armstrong of Succession fame. Baumbach has done some great movies, but I doubt that Jay Kelly will stand the test of time. Looking at the list of awards that the film is nominated for, I’m dismayed but not surprised: this is the kind of gentle send-up that makes Hollywood loves, that let’s the Dream Factory believe it is taking a long, hard look at itself – when really, it’s a milquetoast ribbing by an industry of itself. Jay Kelly is another instance of Hollywood telling itself: it’s not your fault. You’re okay. After all, you bring so much joy to everyone’s lives. In the end, Jay Kelly is as superficially affable and as empty as its title character.