You don’t often come away from a Marvel movie thinking more about the ideas it tackles than about its snarky one-liners or its action setpieces. You don’t often read reactions to a Marvel movie that mention cultural critics, intellectuals and political thinkers. You don’t often see a Marvel movie being taken this personally by this many people, both among its supporters and its detractors. Obviously Black Panther must have done something right.

The internet is already full of reviews and essays of Black Panther, by people more intelligent, erudite and educated in cultural studies than me, so I won’t write a full-length opinion piece on why the film may just be Marvel’s most ambitious, most political film yet. At the same time, we wouldn’t do a good job of serving up fresh cups of our particular blend of current culture if we didn’t say a word or two about it, so here are some of my thoughts on what Black Panther does with themes of culpability, responsibility and inspiration and why I liked what it does.

Culpability

One of the few white characters in Black Panther is referred to, only half-jokingly, as a “coloniser”, and even when it isn’t mentioned explicitly, the topic of colonisation can be read between most of the lines of the film. An early expository sequence bringing the audience up to speed on present-day Wakanda alludes to the exploitation of the African continent by the west, one of the reasons why Wakanda keeps itself and its riches hidden from the world. The museum heist that has Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) and Ulysses Klaue (Andy Serkis) steal – or should that be “reclaim”? – a Wakandan artefact from the “Museum of Great Britain” is not particularly subtle, nor does it need to be, in its reference to another, very similarly named museum that is basically filled with objects pilfered from cultures around the globe, and to many similar museums in former colonialist countries.

However, Black Panther doesn’t make the white, white West into a simple, obvious villain in a way that would make the film about Whiteness and that would play into #notallwhitemen bullshit. Killmonger is as much a product of white dominant culture, having served in the military, fighting in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and learning some very chilling lessons, as he is a product of abandonment by his family and his home. I don’t think Black Panther lets white villains, or indeed white audiences, off the hook by doing so – instead, the films makes sure that it doesn’t strip its characters, and in particular its antagonist, of agency. Erik Killmonger is made what he is by the mistakes and crimes of others, but he is not a puppet. The film is clever in its criticism of the west’s colonial past and neocolonial present without losing sight of what it is about, namely its African and African American characters.

Responsibility

There is a conversation early in the film between T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) and his friend W’Kabi about Wakanda’s isolationism. W’Kabi talks about how Wakanda wouldn’t be able to protect itself from outsiders if it revealed itself to the world. Interestingly, he mentions one kind of ‘intruders’ in particular and argues that they can’t be let in, because “When you let in refugees, they bring their problems with them.”

You don’t have to squint particularly hard to see how that sentence may comment on more than just fictional African country Wakanda.

Black Panther‘s fictional Wakanda is an Afrofuturist dream, it has those flying cars we’ve been dreaming about ever since before the Jetsons. It is also fearful and guards its riches jealously. It is the world’s richest, most powerful coward. Never mind sharing with the world: Wakanda leaves the rest of its continent to its own devices, ignoring war, famine and other humanitarian disasters, when it achieved its wealth and technological prowess through sheer luck. While Killmonger’s ideas on how to help black people around the world may be destructive and driven first and foremost by revenge, he is at least willing to do something, where the Wakanda that had left him behind wasn’t. Old Wakanda was happy to sit on its prosperous, powerful, frightened arse and let the world go to hell.

Inspiration

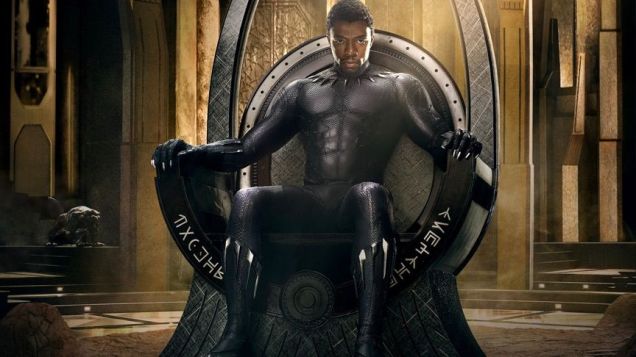

This being a Marvel film, it’s difficult not to hear Uncle Ben’s voice in the back of our heads as we listen to T’Challa argue for Wakanda’s place in the world. All together now: “With great power comes great responsibility.” However, the way in which T’Challa finally makes Wakanda take on this responsibility has little to do with putting on a suit, however cool a suit it is, and beating up bad guys. Black Panther may also be the first Marvel movie that hides one of its most important, most meaningful scenes in the middle of the credits: in it, T’Challa speaks at the UN Assembly, about to reveal the true Wakanda to the world, not as a nation that will strike fear into the hearts of aggressors, exploiters and comic book villains, but as a nation that can give. After his speech, one of the attending UN representatives asks him: “What does a nation of farmers have to offer the rest of the world?” T’Challa looks at the man and smiles. Cut to black.

Yes, there are the flying cars and the armoured rhinos (I want one!). There’s pretty, glowing vibranium. There’s all the cool but unreal comic book stuff. But that’s not the point. That’s not what Wakanda offers, and that’s not why it is important that it doesn’t remain hidden. We’re still all too used to seeing black people in the movies and on TV as thugs, as absentee dads, as drug addicts, as victims of the system. We don’t often see them as inventors, as kings, as heroes.

What Wakanda has to offer, not least to the children who look more like T’Challa than like Captain America, Iron Man or Thor? Inspiration. It would benefit us to recognise this.

One thought on “Fear of a Black Panther”