Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

As our last two posts cleverly pointed out, movies dealing with the end of the world are almost as old as cinema itself. Yet, combined with times of crises, war and disorientation such as the present day seems to be, the genre has always been even more fruitful and frightening.

Just this week, while sitting in the splendid seventh Mission: Impossible installment for a second time, I became aware of how darkly fitting its end-of-the-world premise is to our present fears and insecurities: an artificial intelligence gone rogue threatens to infiltrate the global secret service networks and therefore have mastery over truth itself, spawning conflict, war and ultimately doom for the entire planet. It seems unlikely that the screenwriters of this much delayed blockbuster had much knowledge of how topical their plot would become up to the moment of its release, but it somehow seems to be completely in sync with the warnings of historians, politicians, philosophers and teachers about the ‘end of humanity’ and its enslavement to supercomputers, data and generic creativity. So when secret service mastermind Kittridge (returning from the very first Mission: Impossible in 1996) says that “This is our chance to control the truth; the concepts of right and wrong for everyone for centuries to come”, we are of course shuddering at the relevance of that in a post-Trumpian world but also at the disaster this might spell, now that A.I. seems to have even more pervasive access to all information networks and might be even more disastrously used to win the war on truth.

What calmed my nerves to some extent was the realisation that such doomsday scenarios have always been informed by what we seem to know about an inevitable future and consequently defined by the limitations that puts on our imagination. The apocalypse at the movies has always been just the sum of present-day insecurities and often sums up the zeitgeist of the movies’ release. I’m confident that in a few years, Mission: Impossible Dead Recknoning will stand out as a formidable example of that, but just one in a long line of other examples that eventually weren’t quite so spot on as we felt at the time of their release.

Think back to the early days of movie history, when despite the playful enthusiasm of comedy and adventure, nineteenth century monsters and fears of yet unexplored worlds soon spawned horror and science-fiction scenarios. Universal Studios released its arsenal of evil onto audiences, but only once they had taken pages out of the German expressionist playbook and absorbed most of Europe’s emigrant talent into Hollywood. From it, the heroes and villains of the time were born and they soon expanded to places like the Marvel comic book universe, with Jewish immigrants populating the Californian drawing and sketching rooms, creating superheroes against the fascist threat in their countries of origin. It’s interesting that our past decade has seen such a cinematic exploitation of a universe created almost a century ago. Are the threats and fears of the 1920s and 1930s then much like our own? And what pages do we take out of these books today?

Zeitgeist continued to haunt the movies much beyond the perils of world wars, of course. Soon after, there was a strange surge of aliens, body snatchers and other entities from outer space. Whereas these were seen as a reflection of people‘s actual fears and hopes towards space exploration, it often rather reflected more earthly concerns about communist infiltration or any kind of ‘foreign’ influence. The ‘60s were much more literal about such fears, with Stanley Kubrick‘s Dr Strangelove spelling out its doomsday scenario to the very last consequence. At the same time, manly superheroes were constantly and successfully beating villainous networks seeking world domination, assuring audiences that the Western male had this under control.

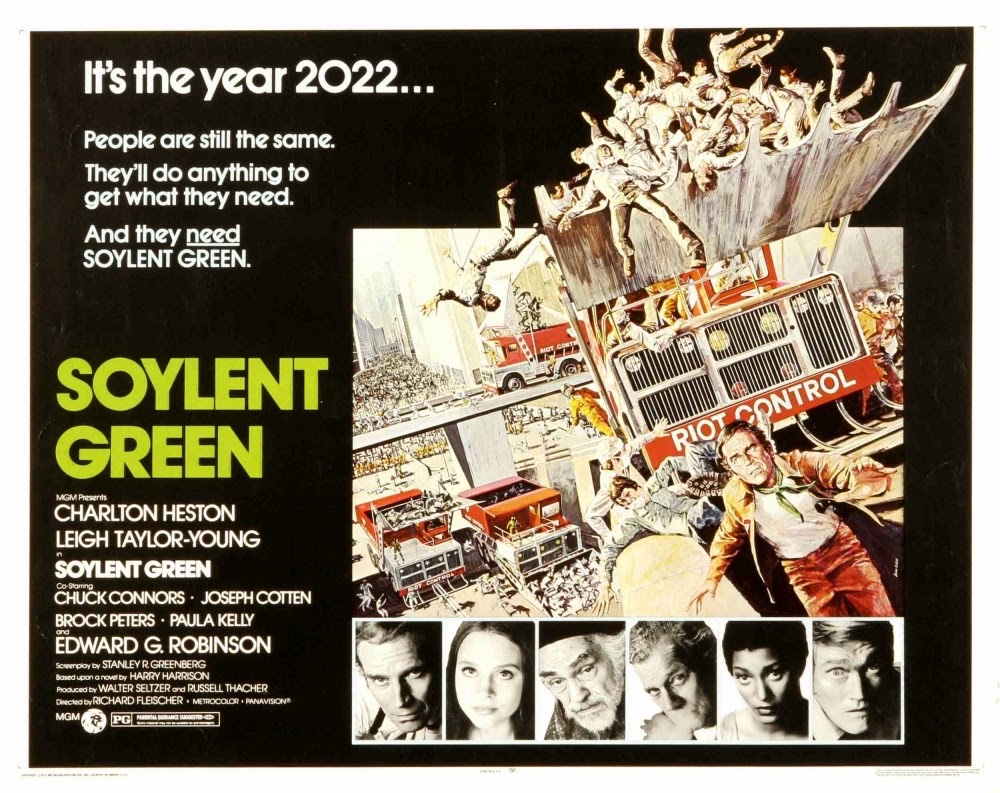

It was also no coincidence that the economic and social crises of the ‘70s culminated in the eco horror of Soylent Green and the disaster genre (interestingly enough many prominently starring uber-male Charlton Heston among a throng of Hollywood has-beens!), which seemed to suggest that the end of the world was either man-made or possibly nature’s revenge for what humanity did to it.

Meteors, earthquakes and plane crashes soon gave way to the yuppie optimism of the ‘80s but the “scuzzy horror” (as my co-barista Alan loves to call and it) continued to simmer just underneath the surface of suburbia. Interestingly enough, one of its most successful examples suggested that the end of the world (or at least many many murders) might arrive in our very nightmares due to unprocessed feelings of guilt.

Since then, we’ve seen a ‘90s reboot of the disaster genre, with Titanic as its most successful representative and multiple volcanoes, alien invasions, infertility and viruses taking over our imagination, years before terrorism, climate change and pandemics made those scenarios seem eerily prophetic and quaintly uncomfortable.

So where are we headed, now that our fears have gone viral and our enemies are digitalising and all-pervasive? Where can we find shelter, and who has the antidote to the current doomsday scenarios? Mission: Impossible 7 gives a deliciously old-school answer to this: Maybe all lies in the hands of a team of secret agents and maybe all they need to do is turn an actual key and simply switch the doomsday machine off.*

If only that made us sleep better at night, in the decades to come. What nightmares may come to cinemas near you, then, is a yet unopened door.

* I giggled at this point because its simplicity reminded me of Leslie Nielsen and Priscilla Presley tripping over the power cord in The Naked Gun, thus stopping that nuclear device from going off (in a silly nod to Goldfinger’s ‘007’ countdown finish). If only it were that easy…!

2 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #139: The key to doomsday cinema”