Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

When Once Upon a Time in Hollywood came out here, in the Netherlands, the lukewarm reactions from my fellow movie-watchers surprised me. To me, Once Upon a Time is probably among Quentin Tarantino’s very best. In it, he runs with the narrative that the murders that Charles Manson and his brainwashed drug-addled gang committed, signalled the end of the ’60s. Prime Tarantino material, in which he can delve into obscure films and serials of the time, preferably westerns, the hyper-masculine culture, and a particular nostalgia for LA in the ’60s. It is, however contradictory that may sound, a revenge fantasy directed at the very violence that ostensibly ended the period. As Joan Didion put it in The White Album:

“Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive travelled like brushfire through the community, and in a sense this is true. The tension broke that day. The paranoia was fulfilled.”

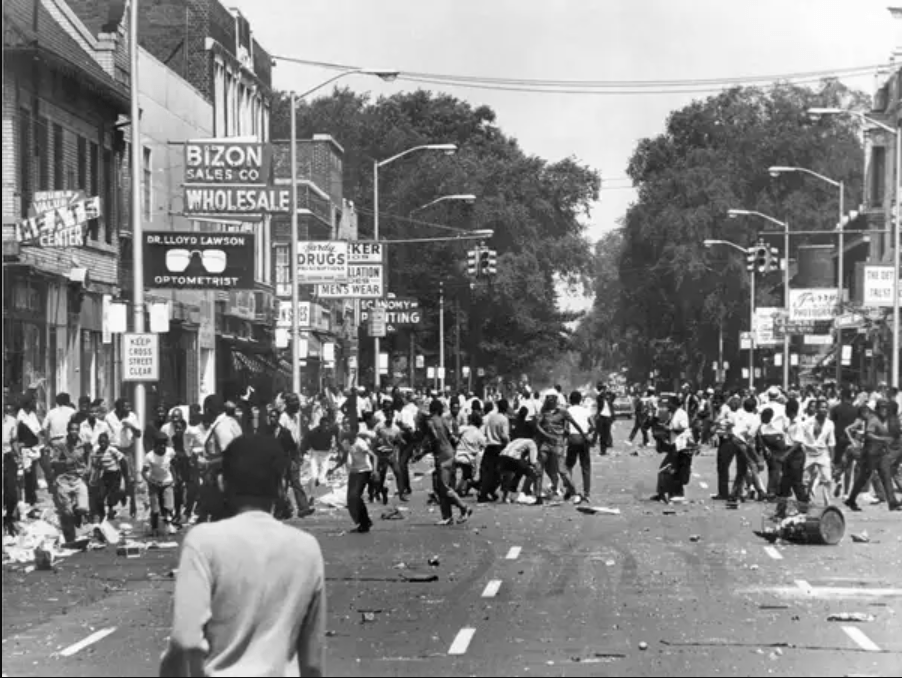

The Hollywood community at the time, however insular, was embedded in the real world rather more firmly than Tarantino’s fantasy depicts. Quite apart from the assassination of John F. Kennedy in ’63, which catapulted Lyndon B. Johnson into the presidency and into an unwinnable war, anti-war protests, race-riots and general unrest were rife throughout the period, as youth-culture turned against the government and also more generally against any and all authority. However insuperable the chasm was between Washington and the culture, there was also a more insidious divide between what was perceived as the establishment and the more left-leaning counterculture.

As a reminder of the timeline, in 1968 on April 4th, Dr Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. In March, Johnson surprisingly and dramatically announced he would not be up for re-election. On June 5th, Robert Kennedy, who had been running on an anti-war, anti-Johnson platform in the ’68 elections, was likewise murdered in cold blood.

The United States had been on fire even before that. Quite apart from issues of the Vietnam war and the draft, deeply rooted issues of racism and exclusion continued to plague the political as well as the social landscape. And where the ’60s in Hollywood had been the era of sweeping and sometimes inflated epics such as Cleopatra (1963), Spartacus (1960) and Doctor Zhivago (1967), in the popular culture foreign films such as the Battle of Algiers (1965) and Jules et Jim (1962) made their way into society’s consciousness.

In Hollywood during the ’60s this cultural momentum seeped through, but only in part. The 1968 Oscars, postponed a mere two days due to the murder of Martin Luther King, were divided between films such as Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, versus Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and Doctor Doolittle. Bonnie & Clyde was a film notorious for its violence and the glorification thereof, with a strong anti-authoritarian streak. Doctor Doolittle was a musical comedy about a man who talks to animals.

As always, the Hollywood system remained closed. If you did not already have connections within it, or managed to garner them, you hadn’t a hope. Films which would in retrospect define the era, such as Easy Rider, were made by (children of) Hollywood royalty such as Henry Fonda. There was a clique of people who, while nominally open to everything, instinctively closed their ranks when faced by outsiders. And, as had always been the case in Hollywood, many of the hopefuls who gravitated to Los Angeles in the hopes of fame and fortune were left shut-out and demoralised. So it went, supposedly, with Charles Manson. He was a criminal, a pimp and con-man with aspirations to become a rock-star, despite his marginal musical talents. To our modern sensibilities he had truly incredible access to the rich and famous. Notoriously living in Dennis Wilson’s (co-founder of The Beach Boys) house, and on his dime, for six full months. He was also in touch with Terry Melcher, Judy Holliday’s son, who made a name for himself by signing bands profitably, in a rapidly changing culture. Manson was ultimately, and in his case justifiably, snubbed. Eerily, Manson had even seen Sharon Tate herself, at her house, where he was shooed away by the photographer Shahrokh Hatami.

Tate, one of the most famous victims of the multitude of crimes the Family committed, is now known mostly as a victim – or if she is remembered in any other way at all, as the wife of Roman Polanski. If you look a little further, she features prominently in The Valley of the Dolls (1967), the unwittingly camp melodrama about doomed women in the entertainment industry. Or in The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967), by Polanski himself, where she is little more than just a pretty lady as scantily clad as they could possibly get away with. (Tarantino, to his credit, features her in neither of these, but in a comedy: The Wrecking Crew (1968).) By all accounts, Tate was more than just pretty, she was breathtakingly beautiful, physically, but if we are to believe her friends, spiritually as well. Tarantino, rightly, makes her the beating heart at the centre of his film, in which he tries to cope with the trauma Manson’s family inflicted on the Hollywood community. Didion again:

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

Didion, as she explains in The White Album, could not impose any narrative thread on these calamities. Tarantino, with many years distance, managed a subversive yet heartfelt attempt.

Sources & further reading

Joan Didion, The White Album (1979), Audiobook Audible Studios, 2013

Joan Didion, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), Audiobook Audible Studios, 2012

Karina Longworth, You Must Remember This, Charles Manson’s Hollywood Podcast (2015)

Joan Didion, The Center Will Not Hold, Documentary (2017)

Lawrence O’Donnel, Playing with Fire: The 1968 Election and the Transformation of American Politics (2017), Audiobook Penguin Audio, 2017

Vincent Bugliosi & Curt Gentry, Helter Skelter (1974), Audiobook Audible Studios, 2011

5 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #145: The Day the Sixties Died”