Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness.

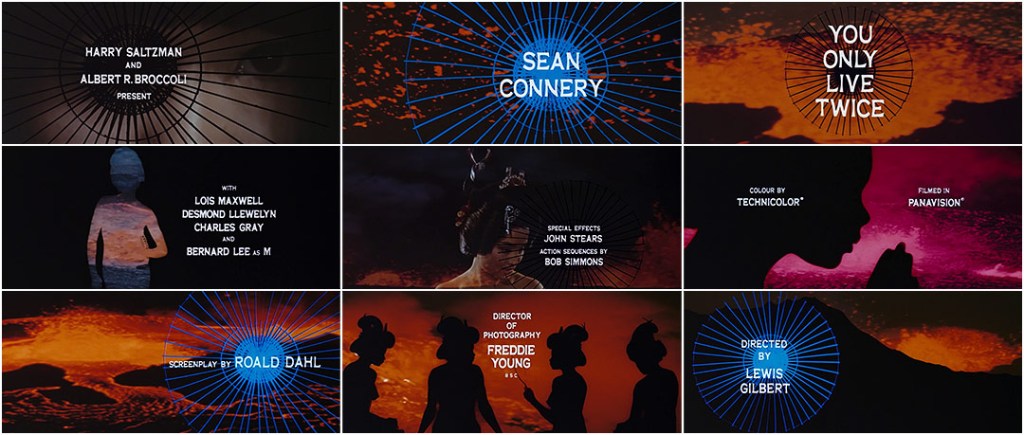

Oddly enough, my first encounter with a Roald Dahl story did not come via Mathilda or Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, nor with The Witches (even though I saw the Anjelica Houston version early and loved it!), Fantastic Mr Fox (so joyfully discussed in Julie’s last post) or one of his many short stories (repeatedly adapted for Alfred Hitchcock Presents). It was that one foray of the world-famous children’s book author and macabre genius into the world of James Bond that I was compulsively obsessed by starting at age 12: his screenplay to 1967’s You Only Live Twice.

Dahl’s is certainly an odd name to come up in a Bond title sequence, especially as Ian Fleming’s original novel’s were not exactly childplay, and the earlier Bond films did dabble in more than just the occasional envelope-pushing scenes of crude violence and overt sexism. Choosing Dahl, however, must have been a more than strong signal that the series at this point was to take another turn, and Dahl’s imagination was the one to conjure it all up.

Just some basic context: You Only Live Twice came fifth in the Bond film series and loosely followed Thunderball in bringing back international terror organisation S.P.E.C.T.R.E with its boss Blofeld (this time played wonderfully by Donald Pleasance) scheming World War III in Japan. Contrary to the novel it is based on, Blofeld had not just killed Bond’s wife (which would happen in the next film, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service) and did not still huddle up with his henchwoman Irma Bunt from the previous story in a Japanese castle by the sea that features a poison garden, only to be found and killed by Bond in the end.

According to Paul Duncan’s comprehensive James Bond Archives production notes, there were first drafts that had Blofeld, Bunt and the castle, but it was the lack of matching locations in Japan that had producers Harry Saltzman, Albert R. ‘Cubby’ Broccoli and director Lewis Gilbert reconsider. Aboard their scouting plane was also famed production designer Ken Adam: “We decided to have the villain live in one of these extinct craters. Cubby gave me a sidelong glance and said: ‘Can you do it?’. The challenge appealed to me”. And that’s where they brought in Roald Dahl.

Watching the film around Christmas again, I was wondering how big Dahl’s influence on the script as this point really was. Was he the one giving it the outlandish space ships that swallowed each other up in space? Did he come up with the bonkers idea of transforming Bond’s Connery into a Japanese fisherman halfway through the movie? Did he devise everybody’s favourite flying machine, mini-helicopter ‘Little Nellie’, or at least the gigantic helicopter snatching off cars with its giant magnet and releasing them at sea (with Connery quipping: “Just a drop in the ocean”)?

Duncan’s production history is quite clear on the fact that most of the elements had already been provided in early treatments by other prolific authors like Sydney Boehm (The Big Heat) and Harold Jack Bloom (TV’s The Man From U.N.C.L.E). They had introduced Bond’s staged death early on in the film, the resurrection of Bond from a submarine after his apparent funeral, as well as Bond teaming up with the head of the Japanese secret service, Tiger Tanaka, as well as his ninjas, to fight the villains. Even an assault on the Russian and American space programs had already been suggested.

Still, that crater got Dahl the job, and once Ken Adam had committed to building it, the crater was the limit! According to Dahl, script sessions must not have been the most exciting experience, however: “I had a few script conferences with Cubby and Harry, and Lewis Gilbert. Harry would go to sleep during them. He’d close his eyes, begin to doze off, then suddenly wake up and come up with quite a good idea.” Dahl also didn’t seem to have that many options when it came to characters: “The producers gave me the precise formula. They said there had to be three women in Bond’s life. The first two get killed and the third one he goes off with.” Hence, Dahl created women accordingly: Japanese agents Aki (Akiko Wakabayashi) and Kissy Suzuki (Mie Hama, dubbed by Nikki van der Zyl), as well as villainess Helga Brandt (played by German actress Karin Dor).

Based on these new ideas, locations and characters, Dahl wrote his final shooting script, but images from production show Dahl wringing his hands over Harry Saltzman’s last-minute rewrites on their Japanese sets. A James Bond film, after all, is a producer’s film, as so many prolific writers and directors have had to find out over the past few decades (Danny Boyle, anyone?), and the final decision has always been theirs.

So doesn’t Dahl seem a particularly odd choice therefore, especially as he hadn’t written a film script in his life before, and as someone who considered it “Fleming’s worst book, with no plot in it which would even make a movie”? Still, even though he only kept a few of the original elements in place and was given the aforementioned Bond girl formula, for the rest of the writing process, he was given free reign by director Lewis Gilbert: “He not only helped in script conferences, but had some good ideas and then left you alone, and when you produced the finished thing, he shot it. Other directors have such an ego that they want to rewrite it and put their own dialogue in, and it’s usually disastrous. What I admired so much about Lewis Gilbert was that he just took the screenplay and shot it. That’s the way to direct: You either trust your writer or you don’t.”

Dahl is also credited by fans for having introduced more sci-fi elements into the Bond series, especially through his interests in the Gemini space programs and the ongoing Cold War space race. The ghastly moment when Blofeld’s evil spacecraft swallows up an American capsule in space (scored gorgeously by John Barry’s space march), is certainly a quirky and eerie opening to the film. Throughout You Only Live Twice, these quirky touches persist and the film is considered the most outlandish of the series until that point: trap doors leading to underground tunnels, piranha ponds eating up unwanted fellow agents (“Bon appétit,” says Connery), poison strings that kill off agent Aki and poisonous caves that almost kill Bond and Kissy are all elements that I suspect Roald Dahl’s twisted imagination had a say in. It seems no coincidence that the film breathes this kind of energy – and that most Bond spoofs (from Johnny English to Austin Powers) take most of their material from this very film.

It’s such a shame, in my view, that Dahl was never asked to come back – and that Blofeld’s poison garden was only finally realised in Bond’s latest adventure, No Time To Die (2021). I’m sure Mr Dahl could have turned more of Fleming’s ideas into delicious entertainment. On that note, an interesting fun fact to finish: according to the James Bond Fan Club article “Spymaker: The secret career of 007 writer Roald Dahl” (which also documents his work for the secret service in World War II), Ian Fleming was the one to come up with the idea of a frozen leg of lamb as a lethal weapon, only to be unfrozen and become untraceable. Famously, Dahl adapted the idea into his 1962 short story “Lamb to the Slaughter”.

The world of Dahl and Bond live more than twice, it seems!

3 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #164: Double-O-Dahl”