Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness.

Here’s a trivia question for you: which actor and director, who famously ended up working together, supposedly shared a boarding house in Munich?

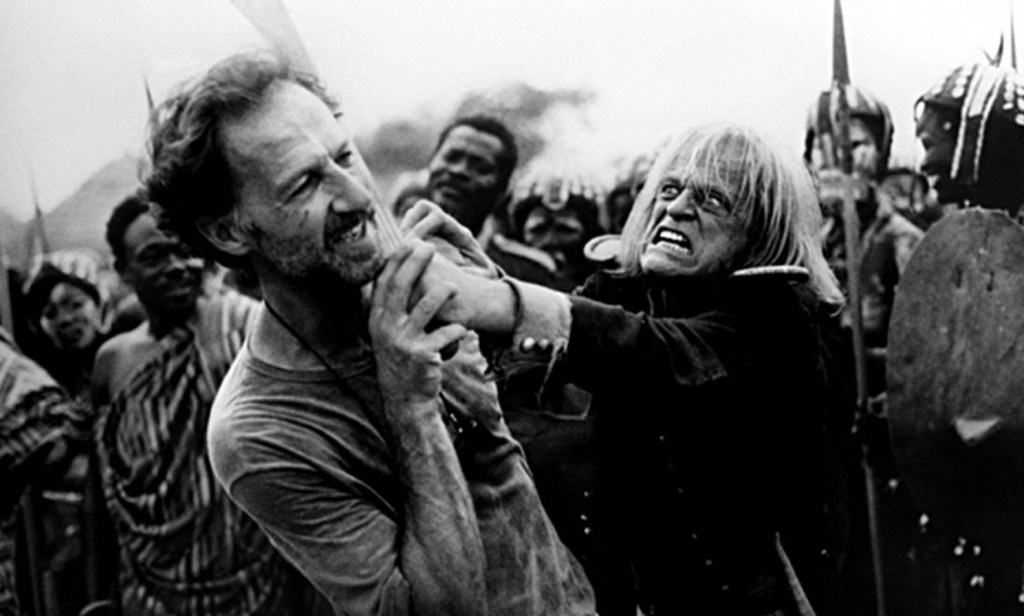

In My Best Fiend (Mein Liebster Feind, 1999), filmmaker Werner Herzog revisits his relationship with the volatile, singular actor Klaus Kinski. In last week’s piece, Alan described Kinski as a monster, which is something Herzog can, and does, attest to. He has many stories about the rages Kinski would get into. In the first scenes he revisits the house that he and Kinski lived in as boarders, describing how Kinski would fly off the handle and destroy the entire bathroom “until the pieces were small enough to sieve through a tennis racket”. He describes several instances of violent clashes between him and the actor, including the most famous one: where he threatened to kill Kinski when he, yet again, seemed determined to storm off the set. It turns out, though, that Herzog did not have had a gun at his disposal during this particular confrontation, which rather diminishes the melodrama of this alleged threat of murder-suicide. Similarly, the story of an outraged tribe offering to kill Kinski has been debunked. Herzog, to his credit, does have the grace to interview the actress Eva Mattes, who did adore Kinski. She praises his warmth, his humanity and his intuition. But while Herzog admits that, indeed, the man was capable of great warmth, he quickly turns back to his quest. And his quest is to make a myth.

For admirers of Herzog’s oeuvre, and I certainly count myself among those, this should come as no surprise. His documentaries are often more beholden to storytelling than they are to literal truth, and they quite often manage to excavate a deeper meaning to the stories he tells, than he would have done with a straight fact-by-fact recounting of his subjects. In Grizzly Man (2005), he examines the life and death of the bear-obsessed Timothy Treadwell, and makes a legend of the vulnerable outsider, who had to create his own heroic cause when his imagined adversaries refused to do it for him. In the most memorable of the Kinski collaborations, the actor too portrays an outsider on an impossible, even insane, quest for an ideal that can never be accomplished. The only redemption, such as it is, is the journey towards the unattainable. Even the documentary Burden of Dreams (1982), about the filming of Fitzcarraldo (1982), features similar themes. Here, the director himself is the protagonist, on a journey to complete an impossible task, the only reason for which seems to be the singular force of his vision.

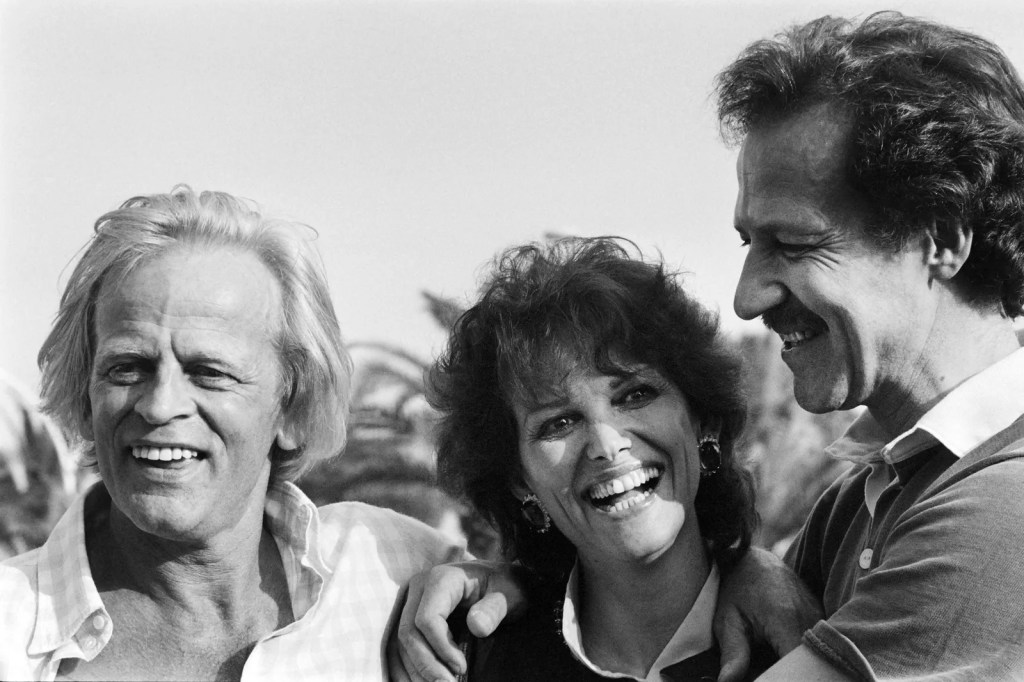

It is no secret that Herzog was able, so to say, to “deal” with Kinski. They made five films together, quite successfully. Kinski apparently even asked Herzog to direct what was meant to be Kinski’s magnum opus: Paganini (1989), which turned out to be Kinski’s last film. Germany was no place for the likes of Klaus Kinski, and Herzog was one of the few of his countrymen who understood how to use him. Even in this documentary there are images of the two men at Telluride sharing a warm hug, basking in their success. Natural enough as, in a way, they defined each other. My Best Fiend, then, is first and foremost a Herzog film. It says less about Kinski than it does about Herzog, again enacting his favourite monomyth. The murderous chaos (one can imagine Herzog intoning) of the environment, as personified by the explosive Klaus Kinski.

And what of Kinski himself? It seems clear he was volatile, prone to rages, with a voracious sexual appetite bordering on the obsessive. He was also involved in much of his own mythmaking, fostering outrage which in many cases turned out to be a detriment to him and his career. He was, by all accounts, a brilliant stage actor, in apparent contradiction to the first scenes of My Best Fiend, in which – in his role of Jesus, no less – he berates and rages at his own audience. (I watched most of this spoken-word performance, without the interruption. It is rather dated, but Kinski seems fine in what seems to me more performance art than an acting role. And yes, there are points where he does go completely off script.) He was vulnerable, prone to overreacting to criticism. He suffered no fools and found it impossible to do mundane interviews, to answer mundane questions. He hated being shackled to even the most minor rules of petty society. In many cases he seemed erratic, because he did things instinctively, for no other reason than because he felt like them. He was gifted, considered an artist in more than one medium. According to his biographer, the many (many) lovers, with whom he conducted his countless affairs were extremely fond of him. Suffering from mental illness throughout his life, sources say he was sometimes suicidal. His preliminary diagnosis was one of schizophrenia*, the subsequent conclusion: he was a psychopath. More seriously yet, allegations of child sexual abuse have been made against him by his own daughters. So yes, if “monster” is your epithet of choice, in many ways he was. But one thing he certainly was not: he was not Herzog’s monster. He was no Prometheus raging against the void, in a futile effort to light it with his personal incandescent flame. So take My Best Fiend for what it is. A saga of Herzog, taking on the roiling chaos of the world in order to find a touch of the sublime, but also a story in which Klaus Kinski ends up being little more than a metaphor.

*Although these diagnoses come from Kinski’s own medical records it is important to note that, in this era, “schizophrenia” was a label used for nearly all mental illnesses, and so should not be confused with a diagnosis of schizophrenia as it would be made today. Likewise, the theory that he was a psychopath invites similar scepticism. It seems clear, though, that by modern standards whatever ailed him went largely untreated.

4 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #168: My Best Fiend”