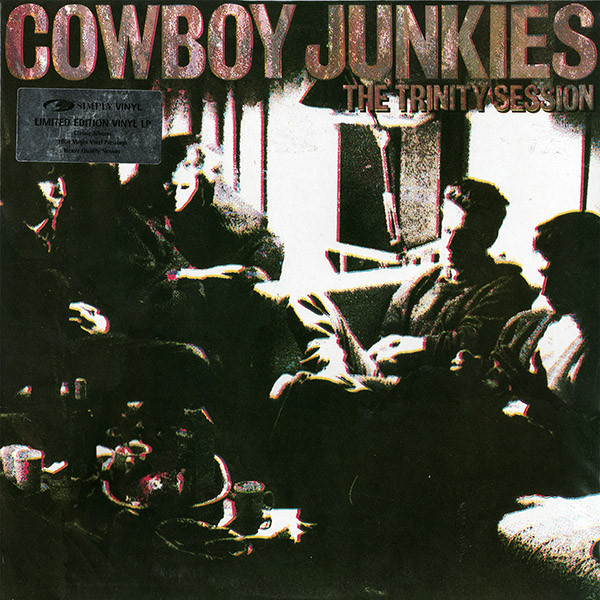

The story goes that Bruce Springsteen recorded his darkest album Nebraska (1982) in his bedroom, most of it in one day. There are absolutely no adornments, no frills, just his voice and his guitar, sometimes a short bit from his harmonica, not much more. He intended those recordings as demo versions, but they just wouldn’t fly when he played them together with his E-Street Band. So the demo version it was for the album for almost all of the songs. Because the Boss is strumming away on his guitar, the effect is one of being there listening, as if it was a live album in a more unusual sense of the word. The same is true for the Cowboy Junkies’ debut album The Trinity Sessions (1988), which was recorded live in Toronto’s Church of the Holy Trinity, and the band gathered around the only microphone. Like with Springsteen’s album, there is an immediateness that would be hard to replicate in any studio.

If I had to transfer the presence of the listener to film, Peter Mullan’s film Tyrannosaur from 2011 is the first example that comes to mind, a movie so stark and realistic that it does not care whether you like it or not. It is hard to imagine that any viewer would want to be an onlooker on the story of violence and abuse, but even here, there is a sense that I am there with the people in the street. I remember Mullan’s character’s desperation and lashing out, Olivia Colman’s devastating monologue, and Eddie Marsan’s character’s heartlessness and deliberate cruelty. As frigging bleak as those characters’ lives are, the movie feels like you are standing at the edge of what’s happening. It has the stink and the feel of real, desperate lives. There is no hiding from the horrible things that happen, or are being talked about, in the movie.

I guess the common denominator of the two albums and the movie is some kind of honesty. As an utter counterexample, it’s always clear that Tony Stark, super-intelligent inventor and flying superhero, does not have much to do with any kind of realism. That is fine, but the smaller the amount of suspension of disbelief must be in any movie or for any kind of music, the better you get to be in the scene or in the song.

Of course I am aware that any movie or song is artificial – for instance, the screenplay puts words in the mouths of the cast that says absolutely zero about their real lives. It is to their credit that they can bring their roles to life to such an extent that we believe for the length of the movie that they mean what they say, up to the point where we sign the deal that we are ready to emotionally manipulated (in the best sense of the word, of course).

I think, however, that the honesty of Nebraska and Tyrannosaur is there in the sense that the music and the movie are not there to entertain (or not only), but that they are there to convey a kind of emotional, psychological state – see here, this is me, I exist. Joseph from Tyrannosaur could exist three doors down from you, and Springsteen has a kind of honesty in his songs that is a sort of trademark. That is also part of the artifice, but the point is that we want to believe that this really is happening somewhere, someplace. That is harder, if not impossible, for movies like Iron Man of The Lord of the Rings to convey.

2 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #181: Reduce it to its bones”