Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness.

“How do you separate reality from an illusion, when you have been trapped in make-believe all your life?” ~ Natalie Wood

Natalie Wood’s life, her death, even her heritage, have become the subject of myth. Reading about her life, it seems suffused with tragic destiny, like the screenplay for a television drama, such as the one Gerald W. Abrams made: The Mystery of Natalie Wood. The many stories that surround her make it difficult to get a sense of the person she was and why she made the choices she made. Because of her mother’s glib and shameless mythmaking about her daughter. Because she was an icon before she had the chance to become a woman, because she was a great star before she had the chance to become a great actress and because she was rarely given the opportunity to be herself. She was a star because it was her mother’s burning desire for her to be one, no matter the cost. But her life, of course, was not a TV script. She was a woman of flesh and blood. Kindly to a fault, a great animal lover and a wonderfully charismatic actor and performer. In the words of Dennis Hopper, apart from her luminous beauty, she was gifted with “honesty, audacity… and balls”. Screenwriter and biographer Gavin Lambert would say of her: “during the 1960s, she was at her professional peak. Enjoying stardom while shrewdly aware of its unreality, she was accessible, loyal, generous, with a pungent sense of humour.” And her friend George Segal put it succinctly when he said of her work: “Nobody could lose control on the screen like Natalie”

Natalia Nikolaevna Zacharenko, or “Natasha”, later Natalie Wood was born in 1938, to Maria Zudilova and Nicholas Zacharenko in San Franscisco. Her mother, known as Mary, Marie, or Musia was, not to put too fine a point on it, a fabulist. She told grandiose stories about herself and her past, intimating she was related to the Romanovs, among other fairy tales. One of the most famous ones was that a gypsy had foretold her she would drown in dark water and her second child would be a great beauty. But then, she had a tendency to fill her child’s head with superstitions and paranoia. About the water, about everything from communists to peacock feathers to sex. Telling her that if she were ever to bear a child, she would die. Detailing with flagrant hyperbole her horrors in childbirth. “God created her,” she would say of Natalie, “but I invented her.” She instilled in her young daughter, so eager to please, a desire, an imperative rather, to become a great star.

To this end, at one point Mary sold the house and went with the entire family, not a penny to their name, to Hollywood, in order to nudge destiny in the right direction. Natalie was five, and already the fate of her entire family was firmly put on her young shoulders. At six Natalie would be rebranded “Natalie Wood” and her persona became her personality. Mary lived vicariously through her, living her own dream through her young child, and the two became so intricately intertwined even Natalie would have trouble pinpointing where her own identity ended and Mary’s began. As would Mary. Natalie’s nature, ever accommodating, coupled with her mother’s burning ambition became a toxic cocktail of co-dependence very early on. Mary’s control over Natalie was total, and she imprinted Natalie with the idea only Mary herself could be trusted. The horror story about the mother making her tiny child cry for a movie scene, by ripping the wings off a butterfly in front of her, is just one example. To compound the misery, Natalie’s home life was a minefield. Her father, rather a romantic type who was disenchanted with being relegated to the lowest rung of the family’s hierarchy, drank. And when he drank he’d get angry. He’d even chase Mary around waving a gun, in the children’s presence. Mary would take the kids to a motel, or to neighbours for the night, and the cycle would begin again after they’d returned home.

Of all the abuse, however, probably one of the most damaging things Mary did to the relationship with Natalie was to interfere with Natalie’s calf-love for a boy named Jimmy Williams. Natalie had her eye on him for quite a while before they started dating. She was proud of him, and he – by all accounts – seems to have been a decent guy. But he was not a powerful Hollywood person, and so Mary came down on the relationship like a ton of bricks. Desperate, the two teens planned an elopement, but finally – inevitably – the relationship had become impossible due to Mary’s relentless sabotage. Jimmy would attempt suicide after the break-up, unsuccessfully, but inflicting a great deal of damage. Like all love affairs of the kind, had it been allowed to progress naturally, it would have probably burned itself out. But Mary, by her obsessive interference in her daughter’s private life, had managed to sow a seed of alienation in her daughter, one that would eventually change the power dynamics between them. While Mary was pathologically controlling about a perfectly ordinary teenage infatuation: she had no compunction at all to send Natalie out by herself to a party with Frank Sinatra and his friends – while she was decidedly underage, a mere child. It is speculated, not unreasonably, the two had a fling of a kind, though it is unsure to what extent. That this would turn into a friendship eventually, was neither here nor there for Mary, who was – to put it coarsely – pimping out her daughter to make her famous, and by extension to give herself the life she craved.

Natalie, at a very young age, would fashion herself as a star. Always glamourous, always bubbling always the consummate little professional. She became the Wonder Child. This persona hid the fact that she was a bundle of severe anxieties. She was afraid to be alone. Apart from being irrational, her many fears were so all-encompassing, they nearly consumed her. During the filming of The Green Promise, she was supposed to run over a bridge, over a torrent of dark water. This frightened her, but her mother assured her she would be safe. The bridge was supposed to collapse after she had crossed it, but it collapsed under her, dropping her into the water below. She managed to grab hold of the bridge and the camera kept rolling. She was, obviously, terrified and had hurt her wrist. But because of Mary’s distrust of doctors, the wrist, which was broken, was never set. It left a small protrusion, which Natalie would cover up with large bracelets for the rest of her life. She was never the same again, haunted by nightmares of drowning ever after.

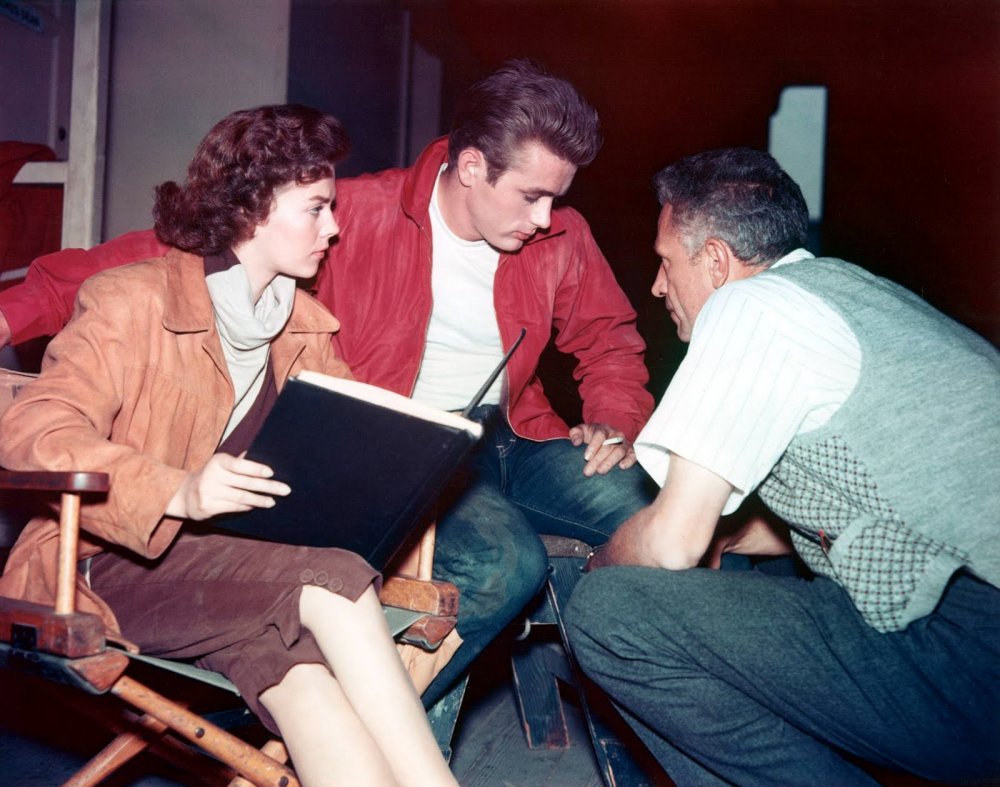

As the child star, with the pigtails and braids, the studio system would not allow her to grow up, and neither would Mary. At 14, she was all but forgotten: too old to play children, too young to play more interesting parts. She met, and became friends with, James Dean just before East of Eden was released early in 1955. His eccentricity and intensity convinced her of one thing, rather than be “just a movie star”, she wanted to be a real actress, a much better option than playing a part created by her mother. And when she was 16, the call came. Her friend Bobby Hyatt (also a child star) informed her he was reading for the part of Plato in a new drama by Nicholas Ray. (The part would eventually go to Sal Mineo.) And there was a part in it that just might be for her. She set her sights on it immediately. It was the part of Judy and the film was to be called Rebel Without a Cause (1955). It was considered a controversial project at the time, so Mary was initially wary. But Natalie desperately wanted the part. “I felt an instant communication with the role,” she would say later. Small wonder, as it was about a teenager’s distorted dream of a faux domestic utopia, with her boyfriend “Jim”. Also played by a “Jimmy”, Jimmy Dean, as Suzanne Finstad notes in her biography Natalie Wood. In Natalie’s mind, so full of ideas of destiny and illusions instilled by her mother, she was Judy. “I felt exactly the way the girl did in the picture towards her parents,” she would say. She got into an affair with Ray, though he was 43, old enough to be her father and she was only 16. According to those around her, it was because she was ‘in love’ with Ray, but it’s very tough, through modern eyes, to overlook the power imbalance. A #MeToo avant la lettre. “He opened the door to a whole new world for me,” she would say much later, as at the time the two were forced to hide their trysts, on account of her being underage.

Though this entanglement might make it seem as though she got the part because of the affair, Ray was reticent about casting her, unsure whether this “child actress” had it in her. She’d gussy herself up, as a teenage girl would, with too much make-up, trying to play the little sophisticate. Both of which did not appeal to Ray, not for that role. But, famously, through hard work Natalie would earn it for herself in the end. She would also develop a crush on James Dean, as so often intermingling the fictional universe of her work, with her separate identity as a real-life person.

Her rebellion was gaining momentum. Rebel had been her own choice of film. Not the glitzy kitschy parts her mother preferred her in. “I was rebelling against being overprotected” she would say, and small wonder. Though, sadly, as many girls in her circumstances do, she looked to (older) men, as her salvation and as her only means of escape. Her growing independence was becoming clear, when Mary consented she would have tutor Tom Hennesy, on the set of Rebel to serve as Natalie’s welfare worker: a point of law for underage actors. The affair with Ray ended, and even before Rebel was released, it became clear she was on her way to become what she so profoundly wanted to be: a serious actress. When Dean died on September 30, 1955, aged only 24, she was shattered. But the cynical fact remains that, through her association with Dean and her own really great work in Rebel, she acquired an iconic status by proxy, almost overnight.

Next up was another role she set her heart on, though this one would not be a film of either budget or great quality. But it introduced her to Raymond Burr, her new infatuation, protector and Pygmalion. Like her last serious affair, Burr was much older than she was and would later confess to his long-time partner Robert Benevides that he had loved her. The studio would have none of it, however. She was to be paired with clean-cut heartthrob Tab Hunter in public functions, such as the 28th Academy Awards in 1956, where Natalie would lose the Oscar to Jo van Vleet, for East of Eden. (Tab Hunter’s story is also an incredibly interesting one, but will have to be told some other time.)Mary did not object too much as she, in her homophobic way, probably considered both men “safe”. (Both would later end up with long-time same-sex partners. But at that time Hollywood was still firmly closeted, and it would have been career suicide for either man to come out as anything but heterosexual.)

After the success of Rebel and her featuring in John Ford’s famous The Searchers, Natalie became more and more famous, and the more famous she became, the more she subsumed her own identity to become the “star” Natalie Wood. Approaching her 18th birthday, Natalie also could still barely function outside of the fantasy world her mother had created for her. She would continue to absorb what were originally her mother’s phobias, as her own. The water, doctors, flying on a plane. Mary, all the while petrified of losing her, resorted to subterfuge to be able to maintain her constant watch over “her” Natalie: her alter ego, the expression of her own ambitions. Then Natalie met, and fell in love with, Scott Marlowe. Also a rebel (a “maverick”, as he called himself), he was smart and sensitive, and the parallels to Dean cannot be ignored. But he was also, perhaps, a bit like Jimmy Williams, the love Natalie had been forced to forfeit, with such tragic results. He got her into therapy, sussing out very quickly the deep and lasting damage that had been done to Natalie. By her mother, but also by the studios. He got her into the Actor’s Studio that Natalie had secretly longed to be a part of, half embarrassed of her Hollywood child-star credentials.

Mary, unsurprisingly, hated that, and hated Marlowe. She did what she could to blacken his name and damage his reputation. She used all her influence with the studio to enlist them to keep Marlowe and Natalie apart. She even enlisted one of Natalie’s close friends, Nick Adams, from the Rebel days, for crass ruses to distract Natalie from her plans to marry Marlowe. And in the end, she succeeded. It is hard now to imagine the sway the studios had over their actors, how they controlled their lives. But in conjunction with Mary’s control, and Natalie’s own internalised vision of becoming a great star, Natalie relented. As she had done those years ago with her Jimmy and, as it was then, another chance at an authentic life, a chance at becoming more herself, had been snuffed out.

But now, on July 20, 1956, Natalie would turn 18. In effigy she burned her studio welfare worker, not out of any malice, but to celebrate her independence. She was no longer a minor and would therefore no longer require a guardian on set, ever.

And on that 18th birthday she would go on an official date with one Robert John Wagner, whose glossy photograph she had pinned on her wall when she was only eleven. Robert “R.J.” Wagner, who she had sworn, at that very young age, she would some day marry… [FIN]

Further reading and sources, apart from the usual online ones:

This article owes an enormous debt to the (definitive) biography: Natasha (2001), by Suzanne Finstad. Published for audio as Natalie Wood, Random House Audio, 2020. Apart from the quotes in the first paragraph (those are from Lambert), quotes were transcribed from her audiobook.

Gavin Lambert: article for The Guardian, and an interview for BFI. His book is called: Natalie Wood: A Life (Knopf, 2004).

More on Rebel Without a Cause here from the AFI.

3 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #191: Natalie Wood, the early years (1938 – 1956)”