Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

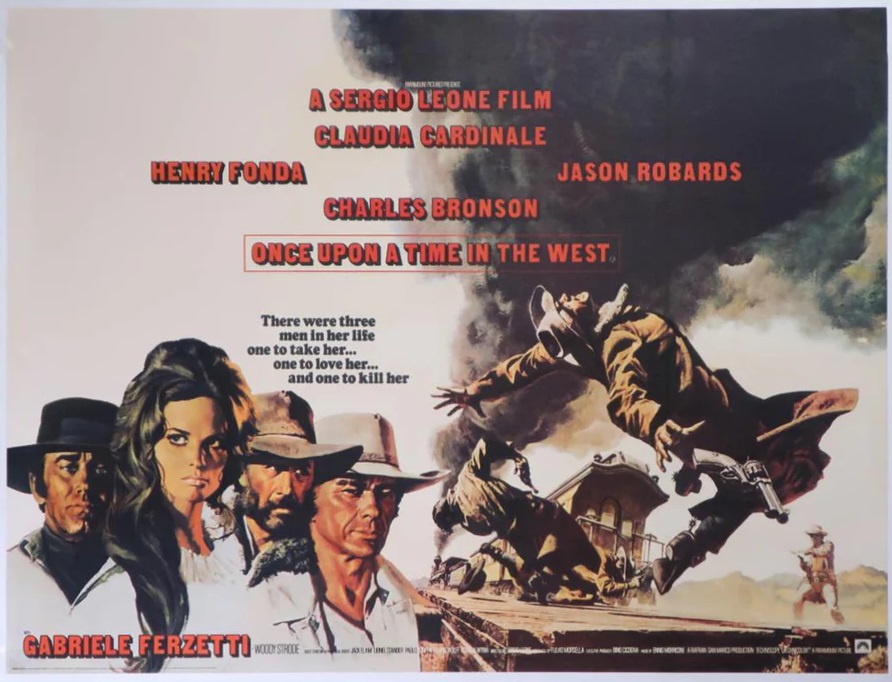

Contrary to the Dollars Trilogy, Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) has the kind of funding that a Paramount production promises. A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For a Few Dollars More (1965) had small budgets. The Good, the Bad and The Ugly (1966) had a slightly bigger budget. But Once Upon a Time in The West has the kind of budget that allows this fictional version of the Old West to come alive in the background, a world with many people and stories, just beyond our perception. It is also interminable. But when I first saw it, at what must have been an entirely inappropriate age, I was mesmerized. The images, the music, the grim world of outlaws, villains and vengeance, all of it imprinted itself on my synapses. I had never seen anything like it. And when I reached the finale after almost three hours, my decidedly underage self was utterly convinced: this was it. A masterpiece! (In my defence, I was too little for Leone at the time, and therefore far, far too young for Visconti). To be sure, back then, a lot of the subject matter that I would now consider to be way too grim for children, went completely over my head. I simply wasn’t bothered. While Bambi had left me inconsolable only a few years earlier, and The Black Cauldron had given me nightmares for weeks: this film just left me awestruck, and simultaneously blissfully unaware of the implications of what I had just seen. The fact that it was subversive, a forbidden treat which at the time neither of my parents would have allowed, only deepened my delight at having seen it. So what better way, to look back on dubious pedagogical choices, dive into the rabbit hole of our collective love of spaghetti westerns, and tie up our own Damn Fine Once Upon a Time trilogy than to discuss this most sprawling of Leone’s films.

The tone is set in the pre credit sequence. In a tiny train station, in the middle of nowhere, three ominous looking men enter. When the elderly clerk tries to tell them tickets are sold at the front office, he is met by a menacing silence. After a pregnant pause, he trundles off muttering to himself “Oh, I s’pose it’ll be alright. What the hell am I doing here anyway,” and returns offering three tickets with a toothless grin. The tickets are received and then simply allowed to flutter off. These men are not here to take any train. After locking the old man up, the wait begins. The windmills screech. The drop drop drop of water is heard. A fly accosts one of the men, who traps it in the barrel of his gun. Still the men wait. Drops fall on a man’s bald head. Stoically, he puts his hat back on to catch the dripping water. The scream of the train, when it comes, cuts through the silence like a chainsaw. The three men are tense, awaiting something, or somebody. And when finally the train again departs, on the other side of the platform stands a man (Charles Bronson), playing three plaintive notes on his harmonica. He is dishevelled, but composed. “You Frank?” he inquires. “No, Frank sent us,” is the curt reply. When asked whether they have brought the man with the harmonica a horse, the response is disdainful: “We are shy one horse.” An almost perceptible shake of the head follows, from the man with the harmonica. “No,” he states “you brought two too many,” as all four men go for their guns. Only one of them will come out alive.

A woman (Claudia Cardinale) gets off a train. She is looking for someone to meet her, but no-one is there. She is unaware of the massacre that has just taken place, which will change the trajectory of her life forever, as she gamely makes her way – on her own – to “Sweetwater”, a farm ironically situated in the middle of the desert.

While, as is made abundantly clear in the intro, the whole film reeks of an overblown machismo that borders on the comedic, it is the woman’s journey which propels the plot forward. When she arrives at Sweetwater farm, only to be confronted with the slaughter that has taken place, she is received by the townspeople. She was supposed to be wed that very day, to the man who built this farm, an old lady commiserates. The woman thinks quickly, and lies that she is already “Mrs McBain”, as they ‘married’ a month ago, in New Orleans. This temporarily allows her to stay at the farm, for reasons of her own. Later we will find out, that there is in fact very little for her to go back to in her hometown. She, like all of our protagonists, is seeking her fortune in the West. Unlike many of our protagonists: she will succeed.

This makes it all the more interesting to see how her part is fleshed out. Whether Cardinale is over- or underdirected: she lacks the spunk and freedom she displayed in a movie like Cartouche (1964), or the gravitas to steal the film outright. But there are distinct moments. When she inspects herself in a mirror, it is not out of vanity. It is to look inside herself, to find the strength to do what she needs to do, and survive. When she is forced to harbour an outlaw (Jason Robards, rather a kindly outlaw), she manages to win him over convincingly. “You deserve better,” he finally remarks. “The last man who told me that is buried out there,” she retorts. When Frank (Henry Fonda) ‘seduces’ her, in what is to my modern eyes possibly the most problematic scene in the movie, very little is left of that agency or her own ideas on the matter. Because by that time, the man with the harmonica has taken over the case, or rather the cause, of this ‘damsel’ in distress. It is up to him to not only save her, but to exact his revenge on Frank, the author of all this misery.

The delights of this film are in its sheer scope and scale, but also the attention to detail. By the time the ending rolls around, audiences who have the attention span for a three hour epic, will be delighted to find that the toothless clerk (Antonio Palombi) from the very beginning has not only survived his ordeal, but has found a new lease on life. And visually, as is always the case with such films, we will have had ample opportunity to inspect every pore and wrinkle on Henry Fonda’s face, whose eyes seem to be lit from within (he makes a very good heavy). Thus we are left with the sense that we were only passengers, for a while, in the lives of characters which seem to live on beyond the film’s storyline. Well. The ones who manage to survive, anyway.

For all its flaws, which are unavoidably and rather uncomfortably, grounded in the film’s gender politics, it is fun to see how influential this film still is. I am inadvertently reminded of the scene in No Country for Old Men (2007), in which an assassin enters a store, and the clerk -intuiting his fate- refuses to give in to his request. The plot itself even reminds me a little of Chinatown (1974), another film about the desert, bad men, and a woman with a dubious past. The list goes on. And though the movie is undoubtedly steeped up to its glinting eyeballs in testosterone: it still makes for a worthwhile journey.

3 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #201: Once Upon a Time …”