Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

In 1925, a short story titled “Traitor Hands” was published in the USA in the detective fiction magazine Flynn’s (later: Detective Fiction Weekly). It was written by Agatha Christie and would be published in the UK in 1933, in a bundle of short stories called The Hound of Death. In 1949, a television adaptation was made for BBC TV. The story would subsequently be adapted for the stage, by Christie herself, who returned to it in 1953 and by 1954 it was one of three Christie plays, running simultaneously in the West End. This play was called Witness for the Prosecution.

While there have been several adaptations of this material – apart from the adaptation for TV mentioned above, there was a 1982 version with Diana Rigg and a 2016 version with Toby Jones -, the most accomplished one is certainly Billy Wilder’s 1957 version starring Marlene Dietrich. Billy Wilder was to co-write and direct the film that would be nominated for six Oscars and won Elsa Lanchester a Golden Globe for best supporting role. Even so, Witness for the Prosecution is not, prima facie, a particularly important film of that era. It came out in the same year as another courtroom drama: 12 Angry Men. The year before, Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man had been released, and 1959 would bring the brilliant Anatomy of a Murder. Still, it remains a firm fan favourite, making the 6th place on the AFI’s best courtroom drama list. It is also significant in other ways, which we will get to later.

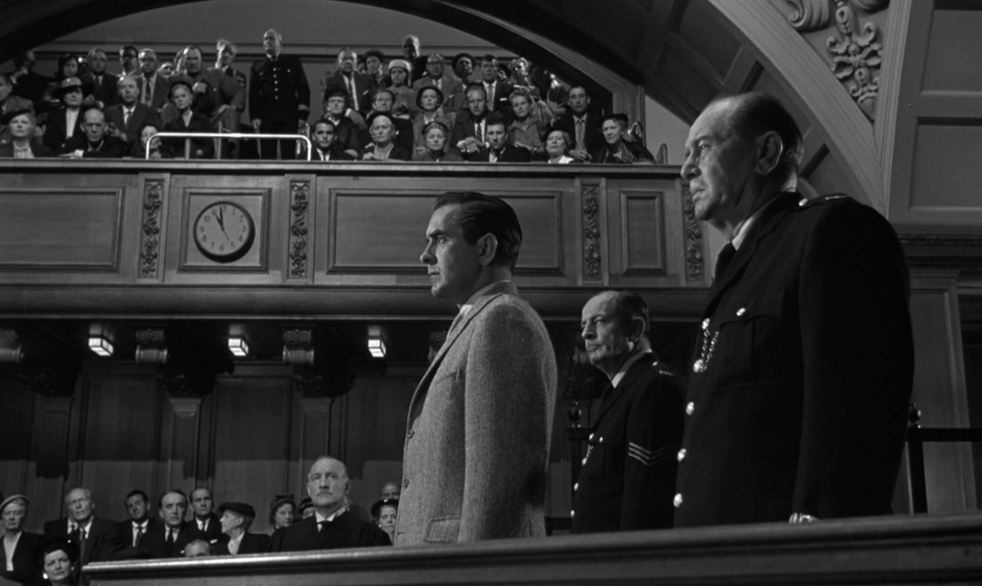

The original short story centres around a woman, Romaine, who is the wife of Leonard Vole (she is called Christine in the film). Vole is accused of the murder of an elderly lady, a Mrs. Emily Jane French, and all the evidence seems to point to him as the perpetrator. His wife is his alibi witness, but in a twist she will become the titular witness for the prosecution. The character through whose eyes we see the plot thicken is barrister Sir Wilfrid Robards, who happens to believe in his client’s innocence and cannot quite make out this mysterious lady, who appears to be very quiet and poised at first, but seems to be smouldering with a great passion and perhaps a secret or two.

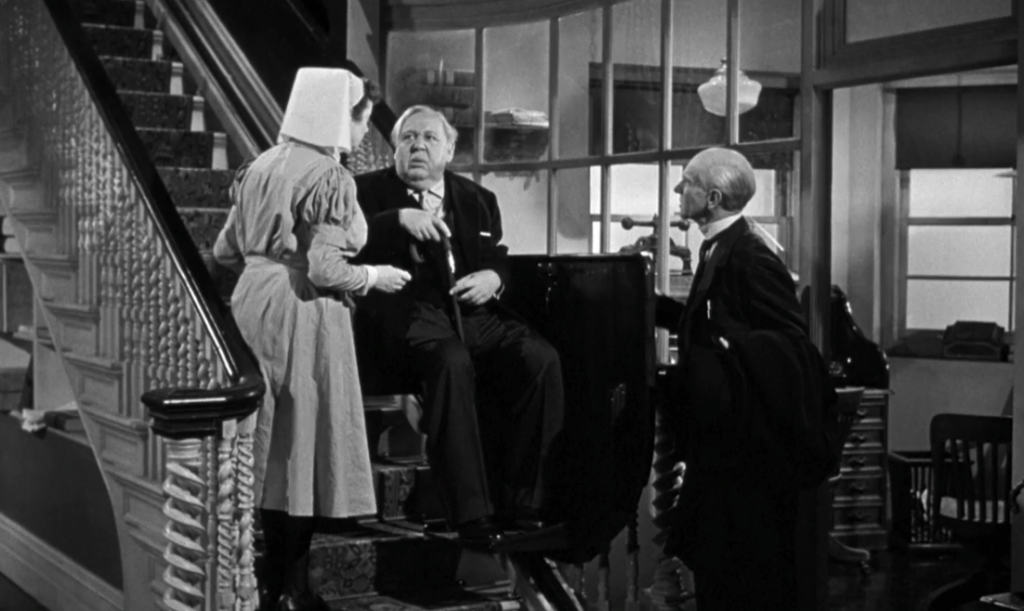

“If we had to invent someone to be the ideal woman for Romaine, we would have to invent Dietrich,” Wilder is reputed to have said. And she is perfect as Christine. Her poise (“Don’t worry, I’m quite disciplined,” she reassures Sir Wilfrid, wiggling her head ever so slightly in amusement), and her severe Edith Head outfits, code her as German. This is significant as, during this period, Germany was still perceived as an enemy of both Britain and the USA. Her star persona, the femme fatale, also slants our perception of her in a very particular direction. Her character Christine, then, is clearly not to be trusted. As in the short story, the film follows the curmudgeonly barrister Sir Wilfrid Robards Q.C. (Charles Laughton), who is just back from the hospital, having suffered a heart attack. To his chagrin he is put on a diet of no alcohol, no cigars and no stressful criminal cases. Accompanying him is nurse Miss Plimsoll (Elsa Lanchester, Laughton’s real-life wife), who cheerfully bullies him into abstaining from these things, and taking proper care of himself. But of course these restrictions are soon waved away by Sir Wilfrid when a murder case comes his way. A murder case to which he finds himself irresistibly drawn, although the secret cigars and brandy he gets to sneak in also help. The rest of the plot is reasonably faithful to the short story, apart for the ending, which Agatha Christie famously adapted for a more visual medium. But the subtext is markedly different. The short story was written in 1925, at the end of one great war; the film was made after the ending of another. It was released in between the signing of the Warsaw Pact and the construction the Berlin Wall, when international relations were tense. It is in this context, we have to place the German-ness of both Christine and Dietrich herself. Rather than just adapting this most British of crime stories, Wilder makes Agatha Christie’s Britain look alien. In one example, Vole (Tyrone Power, cast against type in his last film role), an American, can’t seem to figure out the legal system and insists on calling both solicitor and barrister “Lawyers”. A priceless exchange between barrister and solicitor illustrating the bias against both foreigners and women, is another. Sir Wilfrid to the solicitor Mayhew (Henry Daniell) on the as-yet unknown Christine: “Mrs. Vole, handle her gently especially when you break the news of the arrest. Bear in mind, she’s a foreigner. So be prepared for hysterics and even a fainting spell. Better have smelling salts ready, a box of tissues and a nip of brandy.” Christine, unsurprisingly, has need of none of those things. “I do not think that will be necessary. I never faint because I’m not sure that I will fall gracefully and I never use smelling salts because they puff up the eyes. I’m Christine Vole.”

She is accosted by a mob twice in the film. Once in flasback, where her pants get ripped (these were the same pants she wore in Von Sternberg’s Morocco) because she is a woman, and once after the end of the case because she is demonised as a woman, a foreigner and a witness against a defendant who is perceived as both charming and innocent. After being rescued, she remarks to Sir Wilfrid: “You loathe me, don’t you. Like the people outside.” It is scenes like these that elevate the film from a simple adaptation of a detective story to a film which has a message of its own. Bringing to center stage, and playing off of, the distrust of foreigners in general and Germans in particular must have appealed to both Dietrich and Wilder. The former, German-born, had to flee fascism. The latter, though born in Poland, spent time in both Berlin and Vienna before becoming a naturalized American, after also fleeing the rise of nazism. Dietrich was clearly invested in this story: she actively campaigned for the part, and it was reportedly on her insistence that Wilder was signed to direct.

Small wonder, then, that Dame Agatha herself warmly approved of the film, considering it the finest film derived from one of her stories. And there is more to enjoy. Though the film ultimately belongs to Laughton and Dietrich, it also features – apart from the inimitable Elsa Lanchester – the brilliant and hilarious Una O’Connor. The lovely Norma Varden makes an appearance, for more comedy gold. Often raucously funny and certainly clever, it moves at a decent clip for a film of that era, and has the most important feature every good whodunnit should have: after you’ve seen the final twist and re-watch it in that light, the film still makes perfect sense.

Sources and further reading:

- A similar point to mine has been made, very eloquently and in much more depth, by Steffen Hantke in his article Wilder’s Dietrich: Witness for the Prosecution in the context of the Cold War, (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011), which can be found on JSTOR.

- Agatha Christie facts, come from The Home of Agatha Christie website.

- The other two plays, playing simultaneously with Witness, were The Mousetrap and Spider’s Web. Christie was the first female playwright who had three of her plays running simultaneously.

- My own version of this short story, comes from the US bundle first published in 1948: The Witness for the Prosecution and other stories (audio: HarperAudio, 2012) and is very charmingly read by Christopher Lee.

3 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #205: Witness for the Prosecution”