Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

I don’t remember a time when I didn’t know about Agatha Christie, her stories and her characters. Somehow, Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot have always been around, much like modern mythology. Settings such as the manor house, scenes where a sleuth has assembled all the suspects and lays out all the clues, feckless local law enforcement: I knew all of these – without ever having read a single one of Christie’s novels or short stories or having seen any of the numerous adaptations. Again, I was aware of Margaret Rutherford in black-and-white movies and of Peter Ustinov in glamorous locales, sporting a silly moustache and a sillier accent. But the actual thing passed me by for the longest time.

I probably didn’t read the stories because, all in all, I never really read many crime stories, at least not until I had my James Ellroy and Elmore Leonard phases: the rites of passage of many a male reader who’s also into genre film. I’m not entirely sure why I never watched any of the famous adaptations, though, but I suspect it’s because my mother mostly determined what was watched at home, and her film fare consisted largely of war movies, from The Longest Day and Cruel Sea via The Great Escape to A Bridge Too Far and Das Boot. I cannot be sure, obviously, but it’s very well possible that the first Agatha Christie adaptation I ever saw was Billy Wilder’s Witness for the Prosecution, and at that point I was well into my 20s.

Over the 2016 Christmas holiday, BBC ran a two-part adaptation of Witness for the Prosecution, with a strong cast led by Toby Jones and Andrea Riseborough. However, while the series was based on the same material as the Wilder film, it was a very different beast. Wilder’s Witness isn’t without its darker aspects, but it is an enjoyable and even fun film, in no small part due to Charles Laughton’s performance as Sir Wilfrid Robarts, the barrister who takes on defending murder suspect Leonard Vole. Tonally, the BBC version was the complete opposite: it was dark and oppressive, even leaning towards the dour – to such an extent that I found it difficult to engage much. The cast did an admirable job with the material as interpreted by director Julian Jarrold and writer Sarah Phelbs, but after the fun of Wilder’s adaptation, I simply didn’t manage to get into the right frame of mind to enjoy what they were doing in the 2016 version.

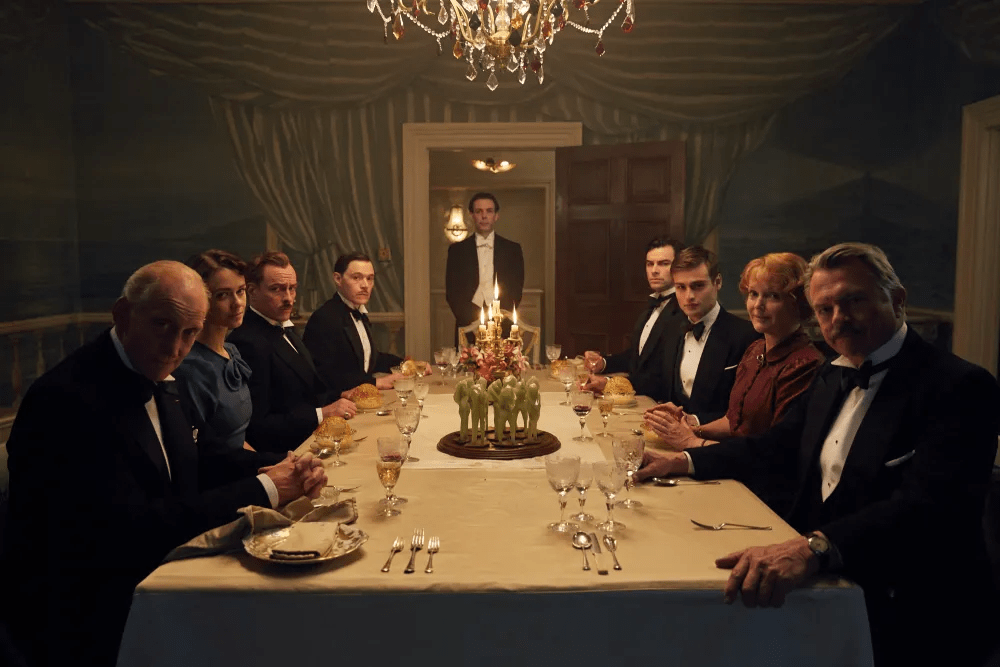

Which is a shame, because only a year earlier, the BBC had shown a three-part adaptation of And Then There Were None (known, perhaps, to some under different titles), also written by Phelbs, though directed by TV veteran Craig Viveiros. This one, too, was impeccably cast, from Charles Dance , Miranda Richardson and Sam Neill to Burn Gorman, Anna Maxwell Martin and Aidan Turner. My wife and I tuned in mainly on the strength of the cast, hoping for a solid adaptation of what at least I expected to be yet another cosy crime classic, with some laughs, some light thrills, and a mystery that would be just right for three episodes. What we got, though, was dark, even chilling, from the atmosphere, which wouldn’t have been out of place in a classic horror film, to the crimes and their resolutions.

I remember loving the series, but also being quite stunned. Had I been wrong about Agatha Christie all this time? Was the image I’d formed in my head, of plump, pleasantly eccentric sleuths and cheeky elderly ladies outsmarting dastardly criminals, of teacups and doilies and murderers of the mildest possible kind, entirely wrong? I imagined at the time that perhaps the adaptation had turned up the dial on the story’s darkness, and certainly the BBC had taken some liberties in turning Christie’s mystery into a Christmas entertainment, but a glance at Wikipedia suggested that the changes had not changed the essence of the story. This was grim, grim stuff.

Nine years later, and I’ve still not read anything by Agatha Christie – but I have caught up on some of the adaptations, at least. I’ve accompanied Peter Ustinov on a steamer travelling down the Nile. I’ve spent a few days on a train stuck in the snow with Albert Finney and with Kenneth Branagh. I’ve been on a different train altogether with Margaret Rutherford, witnessing a murder on yet another train. (So much death on so many trains: as an inveterate user of public transport, I’m surprised I’m still alive!) More recently, I hung out with Will Poulter (who proved to me that he can play characters I don’t want to slap instantly) and Lucy Boynton in a slight but delightful take on Why Didn’t they Ask Evans?, adapted for the small screen by Hugh Laurie. Many of these are much closer to my initial image of the quintessential Agatha Christie mystery. But even these weren’t all light, fluffy, cosy crime. Take the delightful Murder on the Orient Express (I’m talking about the 1974 adaptation, not the leaden version by and with Kenneth Branagh that doesn’t seem to trust its material or its audience): this is a story that is fun, sly and witty – but once you get to the resolution of the titular murder, I suspect you won’t be laughing.

And Then There Were None was a great introduction to this other side of Agatha Christie – and funnily enough, I think it made me more accepting of her cosier mysteries. I like a good bit of darkness in my stories, if the stories are written with darkness in mind or if they at least leave enough space for the possibility of darkness. What I wouldn’t want is a grimdark series of Agatha Christie adaptations. A while ago we watched the BBC version (a-ha!, again we find the Beeb’s fingerprints all over the murder weapon) of Great Expectations, written by Steven Knight and starring the likes of Olivia Colman and Matt Berry – and it was absolutely dreadful. I’m fine with adaptations taking subtext and making it text, but Knight’s take on Dickens’ material felt like dross that a wannabe edgy adolescent wearing only black might come up with: how grim and how dark can you make the material?

If the TV series of And Then There Were None is anything to go by, there’s no need to make Christie’s stories darker than they are. Thinking that they’re all cosy and twee means underestimating them – and making them all dark to please a more modern audience strikes me as unnecessary pandering. There is an audience for fluffy Christie, and there is an audience for darker Christie, and sometimes these two overlap in one and the same story. Trust the audience and the material, and you may just come up with something wonderful.

3 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #206: Cosy? Dark? Why not both?”