Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

I’ve been thinking a lot about vampires recently.

Not related to Halloween, but in relation to work; for reasons that don’t need exploring at this juncture, I’ve been comparing Browning’s Dracula (1931) with Schumacher’s The Lost Boys (1987) and thinking about how the figure of the Vampire – even as it mutates and changes like Seth Brundle on steroids – still speaks to us on a very fundamental level.

Firstly, we have to remember that there is a fundamental difference between the female vampire (Carmilla and her sisters, the daughters of Le Fanu) and the male. The female vampire does not take; she shares. She does not predate, she forms a relationship. She gives as much as she takes, but that giving blurs the line between the vampire and her chosen victim. Although Stephen King is right when he refers to the bite of the vampire as the “ultimate zipless fuck”, it’s always felt that the attack of the female vampire is that much more romantic idea, the ‘kiss of the vampire’. As an aside, it’s worth looking at Single White Female and considering if Jennifer Jason Leigh’s Hedra is, in fact, a vampire. (She totally is.)

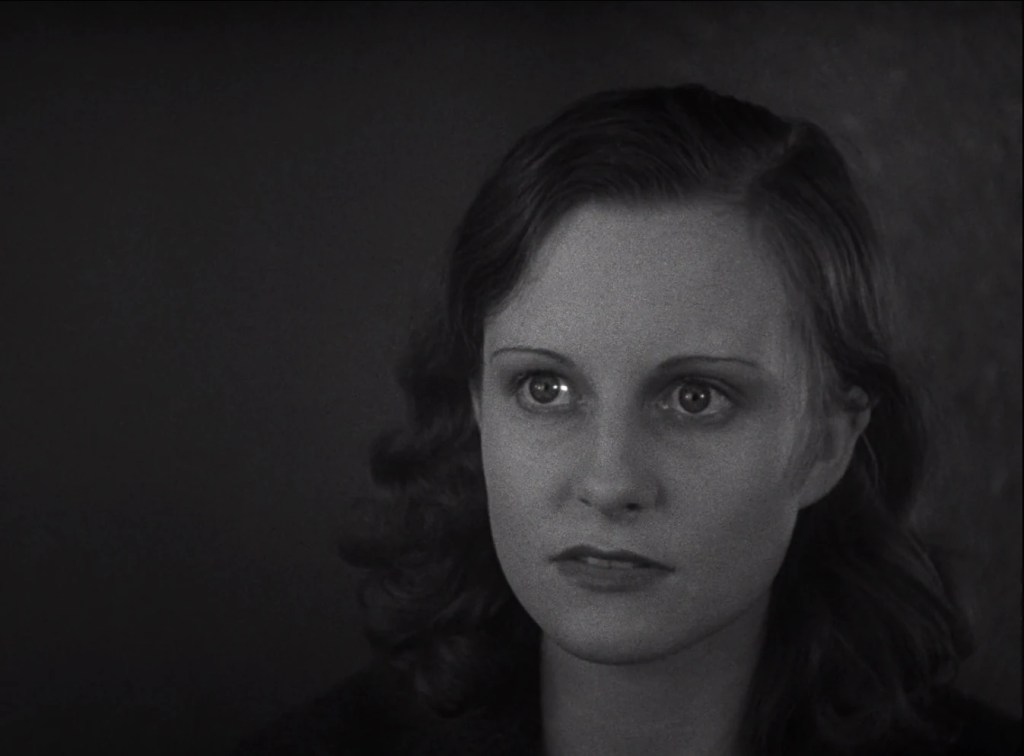

Then there’s the male vampire. He is a predator. He takes. He feeds upon powerless victims. But here we start to find some shades of grey. Lugosi’s Dracula is a Lovecraftian Outside Evil in the form of a dishy foreigner. There’s no sense of enjoyment here, just an endless parade of nameless victims used to stave off the end of an existence that has no meaning anymore beyond continuing. Lee and Jourdan pick up on this in their approach to the Count: the emptiness is there, and the only thing that animates them is hunger. The biggest shift in the character of Dracula, of course, comes with the overt romanticisation of the character in recent decades, beginning with Coppola’s gloriously Grand Guignol entry into the canon. This in itself owes a lot to Anne Rice’s romantic, smoky-eyed Lestat of the ’80s but I’d argue that, fundamentally, the new breed of vampire hasn’t actually changed that much.

You see, the vampire isn’t about blood. Count Dracula isn’t an aristocrat who’s a monster because he’s a vampire. He’s a vampire who’s a monster because he’s an aristocrat. If you haven’t seen the Browning Dracula in a while, it’s worth watching again. Lugosi appears as a walking corpse. Stiff, mannered, noiseless on his feet (a choice by the legendary Jack Foley that I was pleased to notice Hammer kept for Lee’s Dracula – the count’s feet make no noise on any surface), he greets Renfield and invites him deeper into the broken, web-shrouded pile of Castle Dracula. This cold, reptilian performance continues until… well, if you ask most viewers, they’ll tell you that the Count comes to life when Renfield cuts his finger.

But that’s not true.

The Count actually becomes animated and positively lively when he reads the contract for Carfax Abbey, the land he’s buying in London. The count is an aristocrat. He literally feeds off the local peasants to survive – and now he’s coming to England to buy our land and feed off our women. It’s worth looking at who his victims are in this film: Renfield, the dapper – one might almost say flaming – young solicitor who seems terribly excited at coming to Europe to see a handsome older man and has no problem not telling anyone where he’s going. Then there’s Lucy, the liberated young woman who has no interest in a husband, but is happy to show sexual interest in the handsome foreigner. And let’s not forget Dracula’s first victim in London – a working-class flower girl who he devours on the street without anyone batting an eyelid. The Count feeds on the lower classes or those marginalised by society. The man coded as queer, the liberated girl, the working class; Mina, the well-behaved middle-class girl, is saved by the men whose property she rightly is – her father and her fiance, assisted by that ultimate figure of wise old patriarchy, Professor Van Helsing.

But surely all this borderline Marxist nonsense can’t be true of The Lost Boys? Dracula is filtered through late imperial British attitudes and the isolationist xenophobia of 1920s America. Surely a film made in 1987 by an openly gay director won’t be obsessed with class? Surely a purely American vampire isn’t going to be an aristocrat?

Looking at Kiefer Sutherland’s David, he doesn’t seem that aristocratic. He’s a young punk, wearing makeup and coded as at least marginally queer in the way he obsessively pursues Jason Patric’s Michael. I mean, yes, he wears a military greatcoat that looks like a cape, and sure, he’s sporting a medal exactly like the one Lugosi wears, and fine, yes, he sits on a throne made from a wheelchair to hold court with his followers like a peroxide Conan (“What is best in life?” “To make your enemies think they’re eating maggots and put an entire generation of kids off Chinese food.”) but…. Hmmm, maybe he is a little aristocratic.

But the thing people forget is that David isn’t the chief vampire.

So here’s a spoiler warning for a 40-year-old film. I’m about to ruin the cool fakeout. The big daddy vampire is Max. Max, in his suit and tie. Max with his VHS rental business. Max with his unruly family of boy vampires that he wants to turn into a traditional family by acquiring a mother for them in the shape of Michael’s mom, Lucy.

Huh. There’s that name again. This Lucy is liberated and has left her husband and started a new life. But her attempt at freedom is under attack by the man who dresses at the end of the film like a Reaganite Republican senator and wants to put her back in the kitchen where she belongs. In the ’80s, of course, she’s not rescued by the men who own her. She does lack agency, but she’s rescued by the non-traditional, blended – broken, in the terms that Big Ronnie would use and Max would recognise – family.

Oh, but Max… When you look at Max, you see the shadow of the aristocrat. The business owner who wants to acquire, wants to possess, wants to take. And the shadow of Max is there in the small business and big house owner of Salem’s Lot, the Mafia-styled vampires of 30 Days of Night. I can think of only one set of truly working-class American Vampires, in Near Dark, but even they want to possess the young lead, want to take him as their own.

So my final warning to you, my friends, in these darkening days: when a stranger comes to your door and you’re looking for the Mark of the Vampire, forget all the hugger-mugger with mirrors and wolfsbane and garlic. Don’t look for the teeth, don’t look for the pale skin, don’t look for the burning eyes. Look for the true mark of the vampire: a thriving property portfolio and complex tax arrangements.

4 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #208: The Mark Of The Vampire”