Is Roma a sort of stealth sequel to Fellini’s previous film, Satyricon? It can certainly be seen as such: like the film Fellini made three years earlier, it is a sprawling tapestry that is focused less on telling a coherent plot than on moving from episode to episode and from setpiece to setpiece. Where Satyricon depicted, and satirised, ancient Rome, the city’s story is taken into the more recent past and even the present in Roma, making the two films a sort of History of Rome, Parts I & II. But where the earlier film was based on the writings of Petronius, Roma‘s angle is decidedly subjective.

Roma starts with the director’s childhood in Rimini and his late adolescence in Rome – but then the film jumps to the present day, and Fellini is no longer the main character, he’s the filmmaker making a film about the city of Rome – and Roma becomes, what exactly? It’s difficult to pin this down, because Roma is so much: a memoir, a satire, a documentary of sorts, a surreal dream. Some scenes feel like the closest Fellini has ever come to realism, especially in the documentary parts, but even these are stylised and cinematic. Other sequences feel like fever dreams – or like elaborate surrealist skits, prefiguring Monty Python’s comedy in The Meaning of Life and the films Terry Gilliam would make later.

In a way, Fellini’s been making films about Rome for decades at this point: The White Sheik tells the story of a pair of provincial newlyweds getting lost in Rome, literally and metaphorically, on their honeymoon, Nights of Cabiria depicts the ups and downs in the life of a prostitute in post-war Rome, La Dolce Vita is a phantasmagoria of the city through the eyes of a tabloid journalism, and then there’s the aforementioned Satyricon. But in all of these, Rome was a setting, a background, albeit an important one. In Roma, the city itself is arguably the protagonist. Even in the early sequences featuring a young Fellini (played by Peter Gonzalez), he is only an observer, albeit not yet one sitting behind a movie camera.

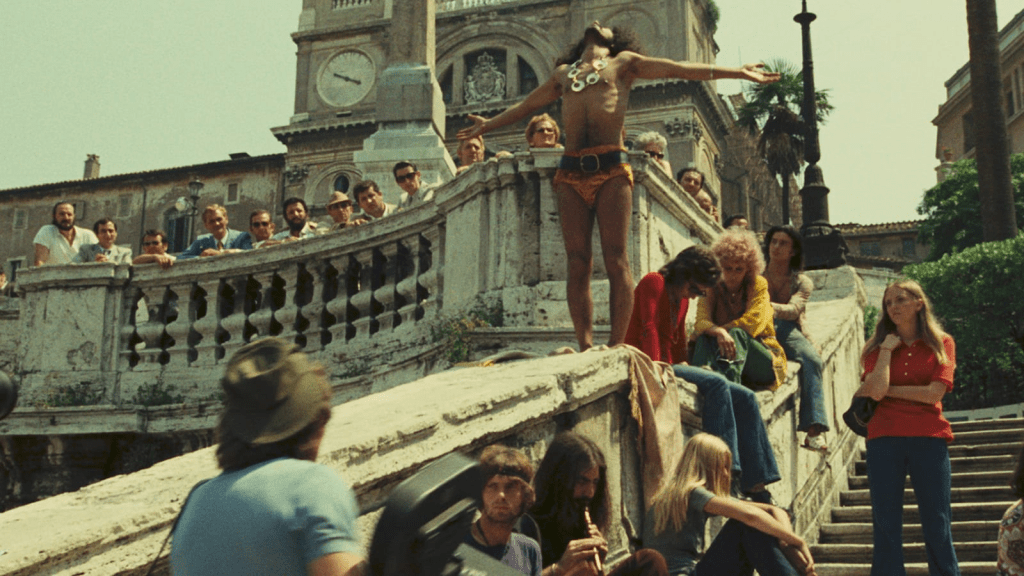

It took me a while to warm to Roma: especially the long sequences just after the young Federico has arrived in the city are loud and crude and overpowering. This is a city that knows only the top-most volume settings, where forte is the bare minimum needed to make yourself heard and forte fortissimo is the bare average. It is a city that is brash and vulgar and fixated on food, shit and sex, not always in this order, and not necessarily making much of a distinction between the three. (Fellini himself talked of the “gastro-sexual” atmosphere of Rome.)

And yet it feels like Roma espouses a certain nostalgia for the time, something I found difficult to relate to. While the city in both eras, the 1930s and the 1970s, is chaotic and cacophonous, there is a clear difference in how Fellini depicts these. There is an alienating quality to much of the film when it shows modern Rome: Fellini as a filmmaker is no longer a part of it, nor is he a guest who’s let in on the noise and the hubbub. The director stands outside and observes, but it is only rarely a look that suggests affection, whereas the Rome of Fellini’s adolescence has a fecundity, a closeness, even something of a clichéd maternal quality that certainly has its ugly, aggressive sides, but that still feels more like a community that Fellini feels himself to be a part of.

Myself, I find the familiarity of the scenes set in Fellini’s childhood and adolescence overpowering and stifling with their blend of the nostalgic and the crude: this is a city that may keep you well-fed, but it will absolutely chew you up and spit you out if you’re not careful. Young Federico is lucky to find one or two people willing to guide him through this inferno, to piazzas, restaurants, brothels – but where the stand-in for the director seems to take it all in with a serene smile, like he’s just found his real home (after his childhood in Rimini), I just wanted to get out. Strangely, though, I found myself responding much better to the later parts and their pervasive sense of alienation, though they seem to keep older Fellini (who is only heard occasionally but who is no longer a character as he was in the earlier parts) at arm’s length.

Whether the director himself still loved his city when he made this film, he infuses his Rome with a poetic strangeness that goes beyond the Felliniesque carnival of his earlier films. There is a longer sequence set in the underground tunnels being dug to create a subway system for the city. We see intellectuals (the filmmakers, perhaps, or academics?) accompany the engineers and tunnel workers through these man-made caves, and there is a spectral, hallucinatory quality to these scenes that reminded me of the magic realism of Kentucky Route Zero. (Are the workers in their hard hats actually there? Are they ghosts, echoes of earlier times? They seem to exist on another plane of existence from the intellectuals who seem like tourists in this underworld.) And then the engineers come across an ancient catacomb with frescoes, not too dissimilar from the ones that Satyricon ended on. We witness the beauty and mystery of ancient Rome – for a few seconds, before they begin to fade and decay, as they are exposed to the air of modern Rome. Again, Fellini seems to say, modernity ruins the past – but he says so with poetic, modern, entirely cinematic means.

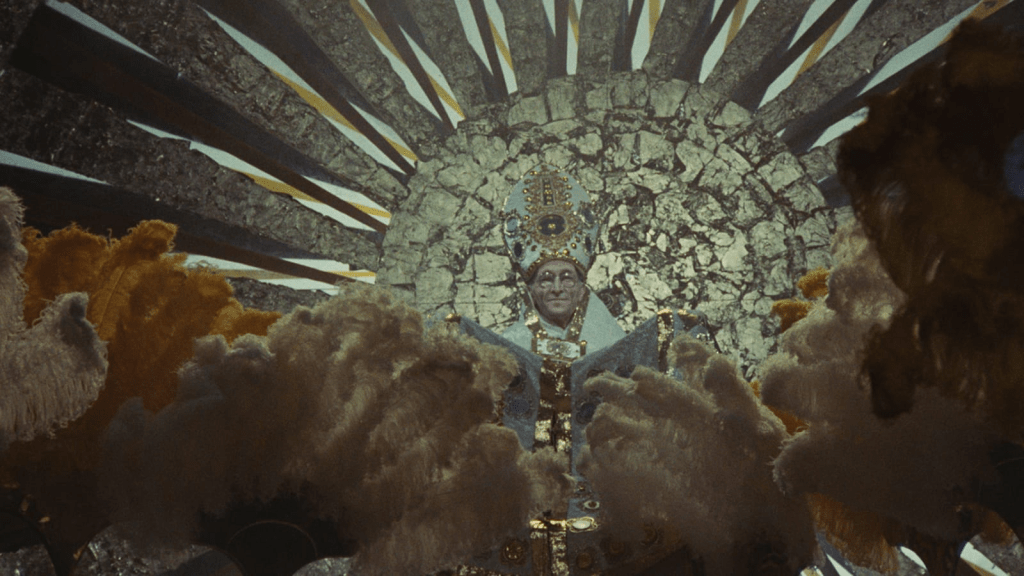

Even when the film is at its most obviously satirical, Roma has a beauty that is strange and even unsettling. Towards the end of the film, we witness a strange event held by an elderly Roman noblewoman pining for the days of yore, when people cared for one another (I’m not sure the scenes set in the 1930s agree altogether, with their sly winks at what’s to come in mid-century Italy, but again, the film’s tone is sometimes difficult to unravel). She has brought together the city’s elite, the rich and powerful, to witness a sort of liturgical fashion show: nuns and priests in the latest outfits, le dernier cri as only the Catholic Church can deliver it. The prancing clergy strutting their stuff on the catwalk elicit laughs, not from the people watching them in the film but from the audience – but the outlandish costumes, somewhere between a carnival and Flash Gordon – segue into something stranger, a surreal dance of death. And all of this echoes the earlier scenes which take us to various Roman brothels, each aimed at a different audience: working joes, the middle classes, the rich, cultured elite. As we first saw the prostitutes advertising their wares, making the rounds in front of men hungry for a glimpse if not a grope, we now see the clergy making the rounds in front of the fashion show’s audience. Is Fellini saying that the Catholic Church is a brothel? I don’t think Roma is this literal – the film makes connections, but it makes them on aesthetic and sensual levels. It works through association: from one kind of cacophony to another, from one sort of chaos to another, from one Rome to another – showing the differences while highlighting the continuities. This is like that – not altogether, not 100%, not literally, but enough to elicit feelings and ideas in the audience.

All of this may make Roma sound too packed, and it is, perhaps like the city it makes its central character. But Fellini wouldn’t be Fellini if he didn’t find space for the odd moment of a more sparse, melancholy poetry – and perhaps none more so than when, shortly before the film comes to an end with a group of motorcyclists tearing up the city with the roar of their engines, the camera comes upon a woman, no longer young, but you couldn’t call her old or even elderly. She turns around, revealing herself to be Anna Magnani, the icon of Italian cinema, but an icon very different from the likes of Sophia Loren or Gina Lollobrigida. Magnani is on her way home late at night, she is tired, and when Fellini and his camera crew approach her, delivering a trite, objectifying monologue on how Magnani is a living symbol for the city of Rome, she turns around and scoffs at their pretentious intellectualising. The actress tells Federico to leave her alone and go home. It is a strange, sweet, funny, beautiful scene (also in the knowledge that Magnani would die not too long after) that is over much too quickly and nonetheless exactly the length it needs to be.

2 thoughts on “Forever Fellini: Roma (1972)”