One of the things that video games can do magnificently is create worlds. These posts are an occasional exploration of games that I love because of where they take me.

In the 1980s and 1990s, video game adaptations of films and TV series were a staple of gaming – or, more precisely, they were a staple of bad gaming. Especially in the ’80s, a video game adaptation usually didn’t look, sound or play much like the movie it was adapting, other than a tinny, chiptune rendition of the main theme. (Sometimes we got lucky, as with Ghostbusters, which would shout a scratchy sampled “Ghostbusters!” and laugh maniacally at the player in the same scratchy voice.) And the gameplay? It’d just be a basic take on a genre that was easily imitated: the side-scrolling shoot’em up or the platformer. Those pixels looking faintly like a human being? They’re Arnold Schwarzenegger killing bad guys. That blocky car-looking thing? That’s your Ferrari Testarossa, you’re Sonny Crockett, and the other cars you’re pursuing in a crude top-down depiction of a city supposed to be Miami, they’re the drug dealers you’re trying to catch. ‘Drive’ your ‘car’ into their ‘cars’ and your score goes up. You’re living the life of a screen hero.

Things got better in the ’90s, at least marginally. By now, computers and video game consoles were becoming advanced enough so that the pixel graphics were recognisable as what they were supposed to depict. Batman looked like Batman, though don’t expect 16-bit Bats to quite have the neo-Gothic style of Tim Burton’s big-screen take on the Caped Crusader. And while most of the adaptations were still 2D shooters and platformers, they started to become more competent – but you were still lucky if the gameplay was even remotely similar to the IP it was supposed to represent. You might jump from platform to platform as Robocop or Luke Skywalker, you might shoot at bad guys as Rambo or James Bond, but the jumping and shooting was pretty much the same – also because there were developers that specialised in quickly done movie tie-ins, to be released at the same time as the film, so they’d hew to the template pretty closely to save time and money.

However, starting around this time, you’d also suddenly get the occasional video game based on movies that was ambitious and interesting. The computers of the time were capable of simulating Star Wars space battles with a degree of fidelity and complexity that contributed to making the X-Wing games classics of the genre: they didn’t only bring a childhood fantasy of many gamers to life, they also did so in the form of great games, which couldn’t be said about most earlier movie adaptations. You had developers such as Lucasfilm Games, which did fantastic work turning the adventures of Indiana Jones not into platformers where you hit Nazis with your whip until they exploded (which, admittedly, doesn’t sound half bad), but into actual adventures of the point-and-click variety. Yes, you still got the usual cheaply produced slop, but you’d also get strange, strange games such as Fight Club, in which you could play Fred Durst of Limp Bizkit fame and beat up Abraham Lincoln, or the terrible but fascinating The Sopranos: Road to Respect, showing that you could now miss the point of the material you were adapting in something approaching hi-def.

These days, you still get games that adapt film and TV IPs, but it’s much rarer that they are The Game of the Movie. It simply takes too much time and money to produce a video game whose production values can live up to player expectations. with average game development cycles taking as long or longer as movie development. What we get instead are games that take an IP but tell their own story, such as last year’s hit Indiana Jones and the Great Circle, or the recent Spider-Man games that are clearly inspired by the MCU (and the comics, obviously) but aren’t bound to the films or their production schedules. That’s how in 2014 we got the amazing survival horror game Alien: Isolation. There had been many adaptations of the Alien franchise by that point, but none had captured the tension and paranoia of Ripley’s original ordeal. Predictably, most games adapting the IP focused instead on Aliens, because that’s what games do well: they let you run around and shoot things until they die. We had many, many opportunities to take our pulse rifles, smart guns and incinerator units to the fight, blasting xenomorphs of all shapes and sizes to bits, in 2D and 3D, with and without Predators added to the mix. Making an Aliens game was a no-brainer: obviously you’re going to make it a shooter, where you run down corridors and blast facehuggers, drones and queens. The later games added some IP-appropriate wrinkles to the mix: motion trackers, acidic blood, that sort of thing. But it was a truth universally acknowledged that a video game developer in possession of the rights to the Alien franchise must make a shooter.

Except, no. There have been fun shooters based on Aliens, and there have been terrible ones. But the shooter genre only goes so far in allowing developers to emulate the tension and release of James Cameron’s Aliens – which already took Ridley Scott’s original and placed it in a different genre, much like those video game move tie-ins of yore.

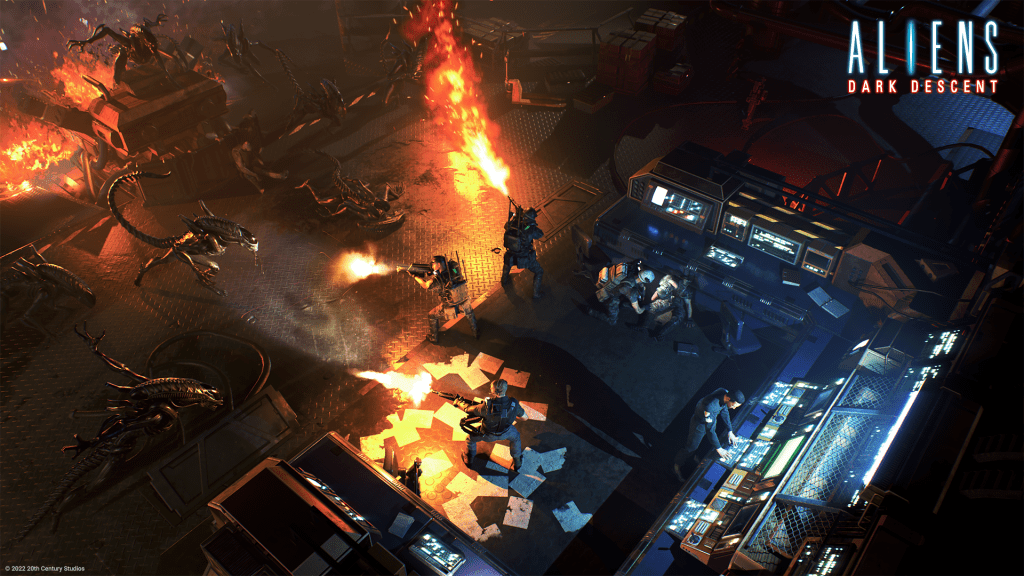

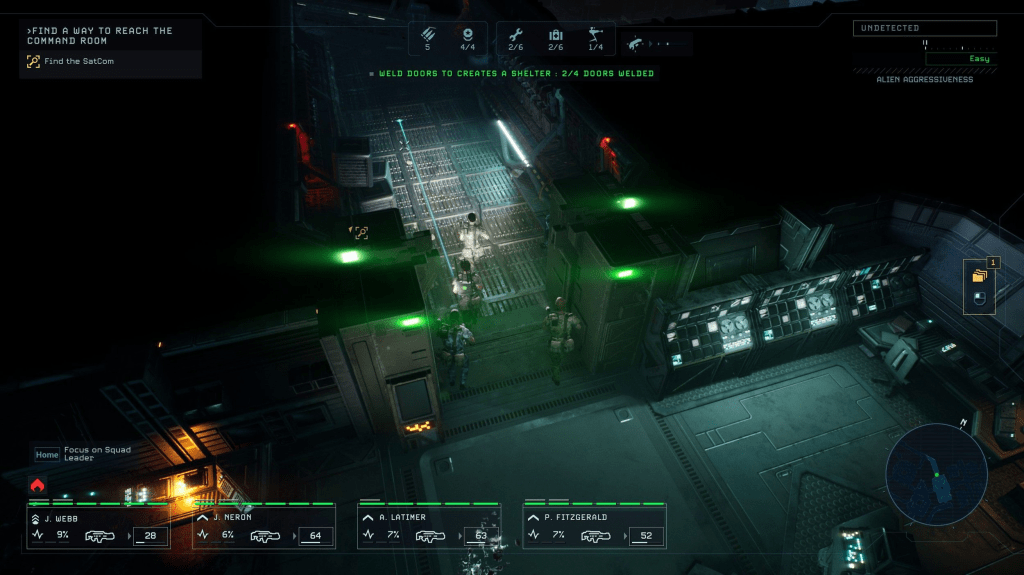

Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve been playing Aliens: Dark Descent. It is perhaps the best video game take on Aliens yet – and it is not a shooter. Instead, it is a tactics game. What, an Aliens game that makes you use your brain much more than your trigger finger? Yes, and it’s this genre that allows the developers to use a much broader palette, getting much closer to what makes Aliens work. Where in a shooter, you’d be there in those corridors, a colonial marine most likely, wielding a big gun, Aliens: Dark Descent puts you in charge of a small squad of these marines – and you’d think that this distancing makes the action more remote, but it doesn’t. Instead, it makes you feel responsible for these poor squishy guys, because you’ve seen Aliens and you know what expects them. Being put at a remove from your men and women takes away some control, but this increases the tension. You tell your squad to go down that corridor, but then you realise that you’ve just put them in the line of sight of a xenomorph, so you order them to withdraw quickly – but you misclick, and instead the alien spots you. Your squad opens fire, and now the swarm knows where your soldiers are. Or you tell them to hide behind some crates and hope that the alien passes by without noticing the cowering humans that may be able to take down one or two xenomorphs with their big, loud guns, but can they withstand a whole, horrific swarm of them, crawling out of their holes and scrambling down the corridors towards your guys?

Aliens: Dark Descent‘s tactics gameplay is full of mechanics and systems that capture the feeling of watching Aliens much more comprehensively than most shooters could. Your marines experience stress, which goes up whenever the swarm is on the hunt and they are trying to remain hidden – and if they become too stressed, they become confused, or their aim gets worse, or worst, they begin to disobey you. Again, the game works as much by taking control away from you as by putting you in charge – and these are gameplay elements that are difficult to implement well in a shooter, because that genre is inherently about control. If your aim is shaky because the game decides it is, that’s just frustrating in a shooter – but in a tactics game, your marines’ aim is one of many variables you’re trying to balance. Do you have time to weld shut that door, so your squad can rest and shake the stress they’ve accumulated during the mission? Do you have enough sentry guns to cover your rear, will you advance slowly towards your objective, making yourself more of a target? Will you just try to leg it to the evac point, knowing that while running you have no way of defending yourself with any effectiveness whatsoever?

If your marines make it back to base, they’ll be wounded and exhausted, they may have developed psychological trauma that either needs to be treated or else it threatens the next mission they go on. You can keep them in your medbay for a day or two longer, but that means letting the xenomorph infestation grow while you’re waiting for your best units to get back into the fight – or you send your newbie marines, barely able to aim straight. Is it an opportunity for them to gain experience, or is it just a suicide mission?

Aliens: Dark Descent is by no means perfect: its story is a hackneyed mashup of clichés from Aliens, and you’ll hear your marines quote the film more often than you care to, so that at times it feels less like you’re commanding a squad of colonial marines than a bunch of movie nerds cosplaying as those marines. And much like James Cameron’s Aliens, the game doesn’t always play fair: that locked door that was to all extents and purposes a wall you couldn’t interact with might suddenly be demolished as an alien queen bursts through and charges at your squad, or a xenomorph, dormant just behind a door, might spring to life as you open it, calling the entire swarm to battle.

But the game is a great example of a medium that, after the dire movie tie-ins of the 1980s and 1990s, has found a way of using cinema as an inspiration while exploring its own potential as an art form more fully. In 1990, an Aliens-inspired game would have you play a pixellated Ellen Ripley armed with a pulse rifle, running from left to right and shooting at xenomorphs charging at you right to left – in ways indistinguishable from a dozen other movie adaptations. In the mid-2020s, you’re effectively Lieutenant Gorman, trying to keep your marines alive and fearing that you’re wildly unqualified. Here it’s less the middling writing that together with the game’s aesthetics captures the world of Aliens, it’s the various gameplay mechanics and systems interacting to bring the colonial marines’ experience to life. Games adapting film and TV IPs have come a long way, finding interesting ways of combining the strengths of the different media. In its early days, gaming would have been better without the frequent, and frequently dreadful, movie tie-ins – but now? The potential is there. Video games adapting movies and TV series no longer need to be nuked from orbit, just to be sure.