Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

Note: as this is a revisit of the 2008 film Bronson there will be many spoilers below.

“Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.” ~ René Magritte

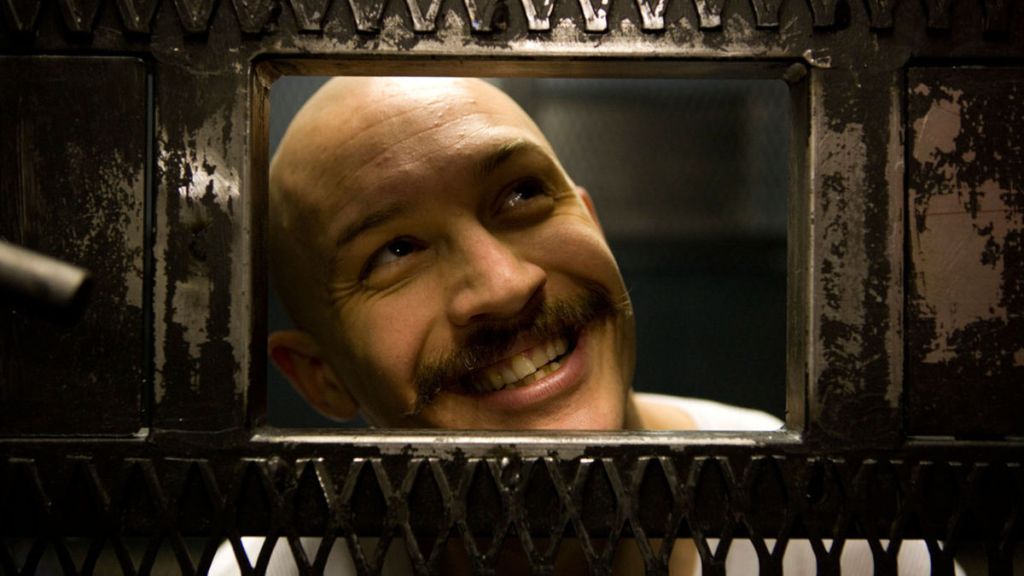

“I wasn’t bad,” Bronson (Tom Hardy) says early in Nicholas Windig Refn’s 2008 film Bronson. Well, “I wasn’t bad bad,” he qualifies. One wonders in that case how bad a person would have to be, to qualify as bad bad, as the film is loosely based on the life and many crimes of Britain’s most violent prisoner.

Born Michael Peterson, he chose the name Charles Bronson as his pseudonym for bare knuckle boxing, which he got into in one of his his brief, and rare, stints out of prison. And yes, so named after the actor Charles Bronson, whose Death Wish, fittingly, is mentioned several times in the film. Most of his life was spent behind bars, much of it in isolation, as he kept committing acts of truly excessive violence and wanton destruction while in detention. Refn makes the wise decision to never quite explain or rationalise his behaviour. The man just enjoys fighting, and doing so gives him both a release and the kind of notoriety he craves. The film is not so much a biopic as it is a warped rendition of the self-portrait Bronson himself might paint. There is a lot of voice-over, and many scenes in which Bronson plays to a fantasy audience on stage, in clown make-up, narrating his own story. His life story, as he tells it, starts in David Copperfield fashion. He was born – “My parents were decent people”, he notes –, he grew up, he had an ordinary life for a while, and then he was arrested for holding up a post office. He is convicted and given seven years, which will extend to more and more time as his behaviour continues to deteriorate.

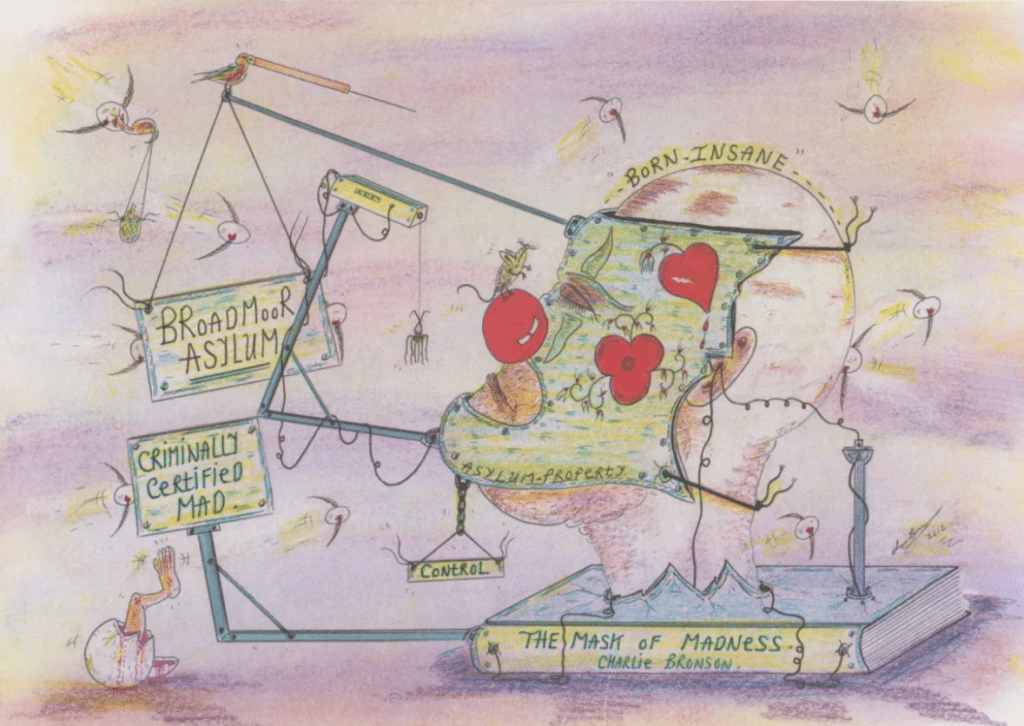

“I had a callin’,” he says, and as he is not particularly suited to anything else, he decides his calling will be violence for its own sake. He likes it in prison, it’s like a stay at a hotel, Bronson quips in voice-over. But when he’s transferred to Broadmoor, he is less pleased when, as a violent inmate, he is forcibly medicated. We are shown a dance at the institution where, to the tune of the Pet Shop Boys‘ “It’s a Sin“, he hobbles towards the door – and his escape – but he is drugged to such an extent that the guards need to do little more than to wave him away. And so he hatches an extreme, and ludicrous, plan to get transferred back to an ordinary prison. He attempts to murder a fellow inmate. In reality he attempted to murder many more than just the one. As in the film he tried to strangle a convicted child rapist: John White, but in reality he tried to murder many other fellow inmates by different means, the silk tie being only one of them. In the film he loudly insists he never murdered anyone, but it should be abundantly clear it’s not for want of trying. The film makes much of the violence Bronson inflicts on others and, incidentally, on himself – often to the most exquisite music. There is a hostage situation late in the film, in which he paints the face of his gagged and bound art teacher as a self-portrait, a reference to Magritte, but also to the film itself, which often reads more as performance art than narrative.

Many critics have given in to the temptation to interpret this very stylized approach to violence as the glorification of it. But Refn’s (and Hardy’s) absolute refusal to psychologise their subject achieves the opposite. He is rabid, his violence has no rhyme or reason, nor does he show the merest twinge of conscience about the suffering he inflicts. The only pity he is capable of is pity towards himself. The film, in contrast, is capable of real empathy for the generally innocent victims of Bronson’s outbursts, albeit only incidentally. This unlike Natural Born Killers or Clockwork Orange, two films it’s often – and rather lazily – compared to.

This really is a plum role for Hardy, who must have had boundless trust in Refn as he is filmed raving, stark naked and bloodie, for so much of its running time. Hardy finds humour in the films excesses, occasionally hams it up with gusto, and looks for all the world like he’s rather enjoying himself. The supporting cast deserve equal praise, with performances ranging from the genuinely affecting, to the drily hilarious. All of them are more than game for Hardy’s mesmerizing performance. Refn himself finds in Bronson an extreme exhibitionist and so shows him progressively disrobed, until he has to be forcibly subdued yet again, stark naked and covered in black paint, to the ethereal tones of the “Flower Duet” from Delibes’ Lakmé. (A raspberry to the use of the the transcendent “Sull’aria” from Mozart’s Nozze di Figaro in The Shawshank Redemption, perhaps?) This, significantly, after a period of relative quiet in a modern facility where he had been productive, working on his art. In reality Bronson would change his name yet again, to Charles Salvador after his favourite artist Salvador Dalí, and his art did in fact win him some acclaim, earning a Koestler Award from the charity of the same name, which focuses on creative expression of (among others) detainees and inmates in secure hospitals.

While the film is distinctly uneven and sometimes unintentionally uncomfortable for quite the wrong reasons, it is a lot of fun to see Hardy – pumped up to a bear of a man – being put into absurd situations. In some cases, for example when he is reunited with his parents in an oddly stilted scene, it doesn’t quite land as either comedy or drama. In others it works surprisingly well and is often howlingly funny. The scenes in the closed psychiatric hospital, though, feel a little like a film student has become rather too enamoured with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and the final hostage scene is perhaps a little smug in how knowingly disturbing it is. But again, Hardy finds something interesting within the exhibition Bronson is about to make of himself. “He’s done!” Bronson howls, for a split second seeming to refer to the man’s palpable distress. But then he repeats: “He is done,” and this time there can be no doubt he views the poor hostage as a mere object he has just ’embellished’. On the whole, the film, while dark, is both humorous and at times incisive. This thug with the operatic moustache and the sometime childlike expression, insists on intentionally disregarding his own evident mental illnesses and vulnerabilities again and again, because he simply prefers to express himself through extreme violence, as an act of self-creation, or simply because little seems to repulse him more than overt vulnerability. The imagery too makes the film worth the watch, as does the juxtaposition of imagery and music. The point being that, as Bronson insists in the film, “They don’t give you a star on the walk of fame for being ‘not bad’,” meaning that, according to him, you have to go to extremes to gain any visibility whatsoever. To go bad bad, in fact. And we are left to wonder what exactly lives there, behind the mask and the acting-out. Whatever there is, if anything, remains hidden behind what we can see.

Refn’s later films are certainly more polished and less uneven, but this one has a vitality that – to my mind – his later ones lack. It is novel, pacy and very violent, as many of his films are, but to me this one is just more interesting, and asks the more interesting questions about performative masculinity run rampant. And, incidentally, of the audience goggling at it in shocked fascination. So if you can stomach the violence, nudity and the self-referential, rather nihilistic message which illuminates nothing and explains even less, this is rather a fabulous bit of cinema. Refn is a consummate stylist and Hardy is a truly spectacular actor. Bronson himself might approve, as he in fact did. He calls Hardy a “genius” and the film “a complete work of art”, in his usual overly hyperbolic fashion. Interesting that Bronson in a self-pitying tone (he is a changed man now, he insists, being disproportionally punished for past behaviour*), seems to feel the film is somehow edifying, as Hardy and Refn ultimately expose the character as an empty, blustering, infantile, grandstanding grotesque. Not only do they firmly refuse to make excuses for him, but they don’t shy away from mocking him relentlessly, frequently to great effect. A remarkably current and, yes, often very funny picture. Though, obviously, it is a Refn after all, not for the faint of heart.

* Bronson’s reaction to the film comes from the archived website for his appeal fund. It can be found here in its entirety.