Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

“Having made sure I was wrong, I went ahead.” ~ Douglas Fairbanks

“Half the people in New York crowded into the Lyric Theatre Sunday night to see The Three Musketeers,” writes famed critic Harriette Underhill in the New York Tribune on August 30, 1921.

“The other half crowded into Fourty Second Street to see Douglas Fairbanks enter the theater, with Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin thrown in for good measure. Inside, the scene in the street was duplicated. Perfectly nice people were ready to knock you down or fall on your bird of paradise in their effort to be nearer to the box which held Douglas and Mary and Charlie.”*

The premiere of The Three Musketeers on Sunday August 28, 1921 was a sensational affair, by all accounts, with a full orchestra and a spoken prologue, delivered by an actor (not Fairbanks, sadly) in D’Artagnan costume. Only two screenings daily, rather than multiple screenings a day, which partly explains the crowds jamming 52nd Street to Broadway and the fact that ticket prices went up from $2 to a whopping $5.** Underhill was certainly not exaggerating when she quotes her taxi driver as saying “Guess there’s a fire,” and continues, “and we guessed so too.”

Douglas Fairbanks had of course buckled several swashes on screen before. He had 28 features under his belt by then. There was Mark of Zorro (1920), which cemented his stardom. The Three Musketeers, however, was huge. Much bigger, even, than Zorro, a small film by comparison. This production had costumes designed by Fairbanks’ stalwart Edward Knoblock supervising Paul Burns and an ensemble cast including Leon Bary (as Athos), Eugene Palette (Aramis) George Siegmann (Porthos) and a delicious Nigel de Brulier as Cardinal Richelieu. It features one scene in which Fairbanks – who was known for doing his own stunts – shows his most challenging feat of acrobatics yet: he makes a cartwheel over a dagger with which he’s simultaneously stabbing one of his foes. A “thrilling, gripping, unadulterated success,” Underhill gushes about this blockbuster extraordinaire, which catapulted Fairbanks from stardom into legend.

The effect of this film of Fairbanks’ career can not be overstated. It allowed him to forge full speed ahead with the ambitious production values that would define the rest of his films. And it would forever link him in the public’s mind with his D’Artagnan.

In hindsight it may seem inevitable that The Three Musketeers got made in the way it got made. And that it would become, by all accounts, a smash hit. But in January 1921 it was still a very daunting call, to decide to start production on it at all. Fairbanks had been considering the project for years, but Hollywood hit a slump in 1921, and financing became all but impossible. Especially a period “costume story”, as Fairbanks called it, was not promising. There had been strikes which crippled several productions: the Ince plant closed for several weeks. But apparently Fairbanks and Pickford’s operation was beloved – and generous – enough to forestall such strikes, and thus Fairbanks proceeded with production of The Three Musketeers: his grandest to date. When it premiered, Underhill notes that Douglas, in his after curtain speech, said he had no idea how big a success it was going to be: “And we, for one,” she ends her review, “believed him.” Small wonder, as no one at the time could have foreseen it, and who but Fairbanks would have even dared to chance it at all.

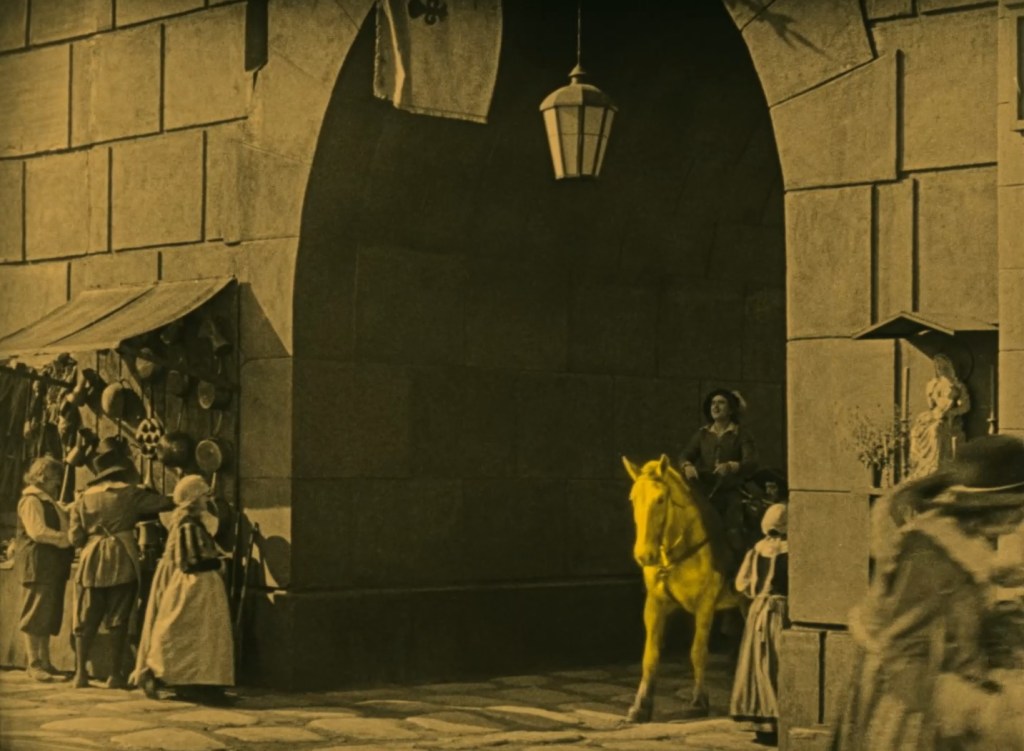

The film itself has been restored to its tinted glory by MoMA, to which Fairbanks donated his entire film collection in 1939. The original film was not black and white, as the stills show, and even had sequences partly colourized with the Handschiegl process, which is a kind of stencilling process, in which colours were applied mechanically to the black and white print, one colour at a time. Which brings us to another great star of The Three Musketeers: Buttercup, D’Artagnan’s noble steed.

The early sequences are played for comedy, and break up the rather long preamble before the action starts in earnest. D’Artagnan, boots too low, his britches too high, his horse too scrawny (and yellow as a buttercup), is a far cry from the belligerent character from the books. This is a Fairbanks character pur sang. Ebullient, funny and fierce, qualities which audiences would forever associate with him. The moustache that he would keep for the rest of his life – and which would become so very fashionable with the gentlemen of the time, who would have insisted on going clean shaven before – was grown for this character. There is a theatricality to the performance that, knowing the naturalism he was capable of, is absolutely intentional and would also stick with him.

The story goes, the fencing instructor was driven to distraction, as Fairbanks insisted on making an exhibition of himself during production. It is, however, worth noting that the action sequences themselves, for all their apparent playfulness, were choreographed to perfection. The individual shots are sustained in length, much moreso than was usual in that era, and rehearsed and practiced endlessly and to spectacular effect. “Such a picture!” Underhill exclaims, and even after more than a hundred years: you can absolutely see where she is coming from.

Sources:

All rights to the stills above, from the beautiful 2021 restauration of The Three Musketeers (1921), rest with The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in collaboration with the Film Preservation Society and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival.

* The full review from the New York Tribune, August 30, 1921, p7 can be found here.

Biographical details from The First King of Hollywood: The Life of Douglas Fairbanks, Tracey Goessel, Chicago Review Press, 2015 (leading quote: p 257)

** and from Silentfilm.org an essay adapted from a chapter of Douglas Fairbanks, by Jeffrey Vance University of California Press, 2008.