One of the things that video games can do magnificently is create worlds. These posts are an occasional exploration of games that I love because of where they take me.

There are a number of films that have been immensely influential on video games. Their thumbprints can be found all over gaming. An obvious example of this is Aliens; even beyond actual adaptations of the IP, you find the trope of space marines fighting insectoid xeno creepy-crawlies on hostile planets again and again – and sometimes, ironically, it’s the literal, licensed Aliens spin-offs that are among the games worst at replicating the Aliens playbook, more so than the games that are basically Aliens with the registration number filed off.

Another one of the clear inspirations for many games are the Indiana Jones films. It’s a perfect match, really: Indy makes for an appealing character type that gamers would want to play, there’s the appeal of mysterious legends and foreboding ruins, and the films are even structured in ways that lend themselves to being translated into the gaming medium: find artefact A, which opens door B, behind which there’s puzzle C, and so on, leading to legendary MacGuffin Z. Cue end credits.

And yet: there’s a certain magic to actual Indiana Jones that evades a lot of the Jones-likes in the medium. As successful as Lara Croft was in her day, in the end she is an off-brand, straight-to-DVD Indy-but-with-boobs. And while Uncharted‘s Nathan Drake (the character from the games, not the lacklustre attempt to turn him into a movie protagonist played by Tom Holland) is a suitably appealing modern Indy knock-off, he too comes second to the O.G. archaeologist with a whip who’s scared of snakes and hates Nazis.

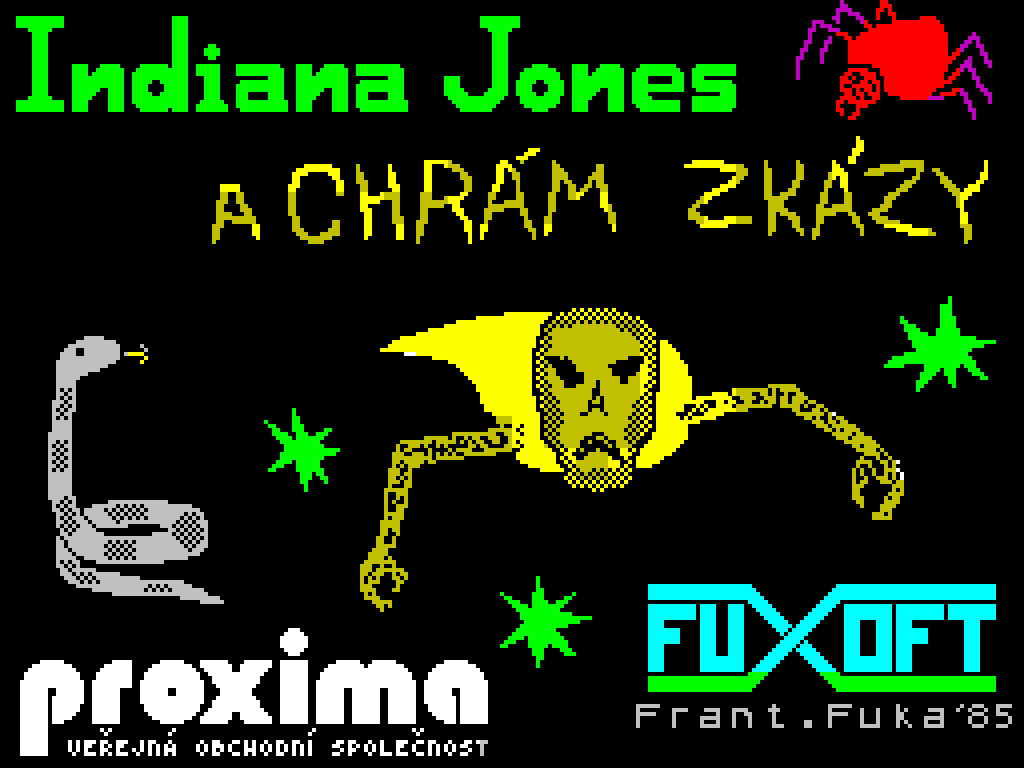

There have been a number of actual Indiana Jones games pretty much from the start – including, most oddly, a 1985 Czech text adventure for the ultra-’80s ZX Spectrum called Indiana Jones a Chrám zkázy (which I suspect may not have been an officially licensed product, judging from its title screen). There were the usual cheaply produced licensed games released to coincide with the release of Raiders of the Lost Ark, Temple of Doom and The Last Crusade, which were little more than generic games with a slapdash coat of Indiana Jones paint applied more or less effectively. (Less, usually.) Beyond a sad, tinny reproduction of the iconic “Raiders March” and the hero sprite having what could be interpreted as a hat on its head, they didn’t much feel like the adventures we’d been watching on the big screen and on VHS tapes.

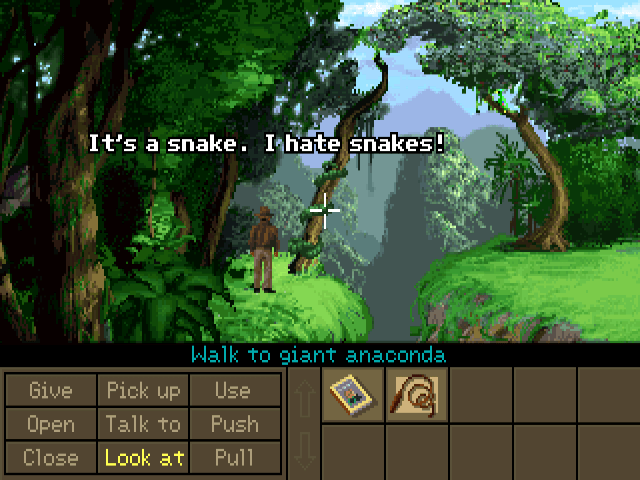

This changed when the masters of point-and-click adventures at Lucasfilm Games (the video game company founded by George Lucas, the creator of the character, with help from Steven Spielberg, Philip Kaufman and a love of the movie serials of the 1930s and 1940s) took a stab at the character, making first Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure (which, sadly, our Sam bounced off of decades ago) and then, in 1992, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. Compared to the video games of the last decade or two, both of these are endearingly lo-fi, but they’re crafted with a love for the material and an understanding of how the character could work in a video game. While the Indiana Jones films are action adventures, action games in the ’80s and early ’90s were largely basic and repetitive, so the developers leaned into the adventure side of things – and what an adventure especially Fate of Atlantis was! Once again, Indy races against time and against dastardly Nazis to solve the mystery of the sunken city of Atlantis. There’s probably an element of gamer nostalgia to this, but Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis felt like a worthy continuation of the movies, more so than some of the later big-screen instalments, featuring a feisty female companion who’s more than just a damsel in distress, great setpieces, and a suitably mysterious legend around which the plot is built up.

Sadly, as video games became more impressive in terms of graphics and technology, point-and-click adventure games stopped being a format that would sell in sufficiently large numbers. Players wanted more action, more spectacle, they wanted 3D – even if the environments of early 3D games were blocky and basic, such as in 1999’s Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine, a game that, ironically, played less like an original Indiana Jones adventure than like an inferior rip-off of Tomb Raider, whose lead Lara Croft was the new hotness at the time – even though she herself was basically a B-movie riff on the franchise that had made archaeology cool.

Fast-forward 25 years: over time, there were plenty more Indiana Jones games, from the obligatory Lego spin-offs which recreated the best moments of the films in goofy Lego blocks to cheapo mobile phone games. But there was nothing as good as Fate of Atlantis, and definitely nothing as big as the tentpole movies that had made the franchise. Indiana Jones in video-game format was old hat, it sold okay at best, but there was something sad to seeing how one of the biggest names in blockbuster cinema had become rather small. That is, until 2021, when Lucasfilm Games (which, after a few decades of being called LucasArts, had returned to its original name) announced that MachineGames, the creators of the successful Wolfenstein games of the 2010s, was developing a new game in the franchise.

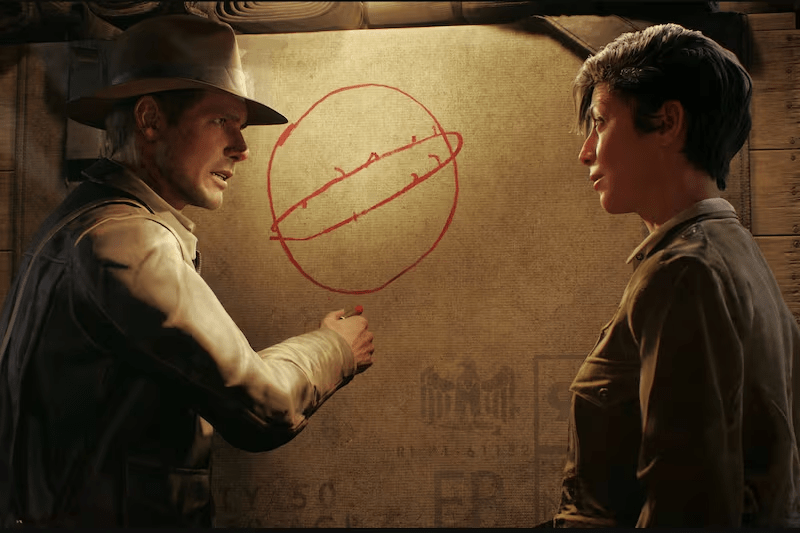

Indiana Jones and the Great Circle came out last year to great acclaim, both by critics and gamers. I only got around to playing it a month or so ago, but I can see why. For the first time since the adventure games of 1989 and 1992, it feels like we have an Indiana Jones adventure that can actually live up to the films in the series – and when I say that, I mean that The Great Circle lives up to the likes of Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Last Crusade, rather than to Kingdom of the Crystal Skull or Dial of Destiny. A large part of this is that the story and script are actually good: not just functional, not just adequate, but fun and exciting, deftly balancing the pulp adventure and the screwball comedy of the best films in the series. This is matched by the game’s production values: the characters, both allies and antagonists, are as well acted as they are written, with female lead Gina Lombardi (played by Alessandra Mastronardi) and main villain Emmerich Voss (a Nazi archaeologist played by Marios Gavrilis) standing out especially. Troy Baker’s performance (voice and motion capture) as Indiana Jones just about one year after Raiders of the Lost Ark also stands out, getting the character just right and elevating the performance into something much more than a mere impersonation of Harrison Ford forty years younger than the real deal. The locations and setpieces too are perfectly chosen for a grand Indiana Jones adventure, with Indy exploring Vatican City (both over- and underground), the pyramids of Gizeh and the jungles of Sukhotai, Siam, following the trail of the Nephilim Order and the legendary Great Circle of sacred religious sites across the world and punching many a Nazi goon and Italian fascist in the process.

However, those are mostly things that are not just unique to video games, so what makes The Great Circle a great video game as well as a great Indiana Jones adventure? It’s how the designers have found ways of making the game fit the character. There’ve been other video game protagonists following the footsteps of Indy, but they were video game protagonists first and characters second. Outside the cutscenes, they were interchangeable. In creating their take on Indy, Machine Games decided that the character is a reluctant action hero: differently from the protagonists of so many games and films, he doesn’t go in guns blazing. If anything, he uses his smarts, or his whip, or his fists. Indiana Jones isn’t a fedora-wearing John Wick in a leather jacket – and that’s where another key element comes in: Indy is a bit of a klutz. Already in Raiders, the action sequences are as much slapstick as they are adrenaline-fests. While he’s certainly the most physical archaeologist to ever go on adventures, Indy is prone to pratfalls and to being outmatched, getting into scraps by accident and out of fights by luck and comedic timing.

The Indiana Jones of The Great Circle isn’t a power fantasy, he doesn’t knock out a hundred Nazis before breakfast, and he definitely doesn’t mow them down the way that Nathan Drake gets rid of the generic henchmen in his adventures. He grabs an impromptu weapon, which might be a hammer or a shovel, or something less immediately impressive: a broom, a frying pan or a fly swat. If he’s lucky, he’ll knock out the guard who’s conveniently got his back turned, but it’s just as likely that he’ll alert the guard’s two friends that he’s now facing with the splintered remains of the mandolin he grabbed moments earlier in the Blackshirts’ living quarters. Indy will get in and out of scraps if there’s no alternative, but he’s better served by going in stealthily – and finding a worker’s outfit or a uniform (which hopefully fits better than the Nazi uniform two sizes too small in Raiders) to disguise himself and sneak into the tombs beneath the Great Sphinx (which, like in real life, isn’t nearly as great as we’ve been lead to believe). Until our hero bumps into a commanding officer who realises that this ruggedly handsome man in uniform isn’t one of his subordinates and his handful of German phrases come with a heavy accent – at which point it’s back to biffing fascists with whatever implements are at hand.

Obviously there’s more to getting Indiana Jones right than a fighting system that’s endearingly clumsy by design – but it’s indicative of the ways Machine Games have understood the material they’re working with. Their Indy is weary and more than a little cynical, but his jadedness hides a more idealistic, even romantic heart that’s revealed whenever he figures out some centuries-old contraption and stands there in wonder at what he’s just found: an inscription, a shrine, an ancient mechanism. The developers have even found smart ways of softening the colonialist and exoticist slant of the films without losing the old-timey charm of the stories and characters, so when Indy now indicates that a certain artefact doesn’t belong in the hands of some Nazi grave robber but rather in a museum, that museum is more likely to be a local one rather than on show at M Marshall College, Connecticut.

There is something a bit sad that one of the best instalments in the adventures of Indiana Jones isn’t a big-screen movie but a video game – but cinema’s loss is gaming’s gain. It’s rare that the medium gets adaptation this right, even when the original material seems well suited to gaming to begin with. Obviously, for all the overlap between cinema and cinematic, story-driven games, the two are different beasts – but the ways in which Indiana Jones and the Great Circle manages to both feel just right as one of Indy’s big adventures and as a game, which comes with its own conventions, speaks both for the respect that Machine Games brought to the franchise and their skill at the medium they work in. Considering how Dr Henry Jones Jr.’s cinematic adventures developed, and arguably faltered, over the years, I’m hesitant to hope for a sequel – but at least a digital Indiana Jones can remain the right age he needs to be to face the many perils he encounters on his journeys. It’s unlikely that Machine Games will give us Indiana Jones and the First Zimmer Frame any time soon.