Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

Despite not ending up as the lead in Billy Wilder’s Kiss Me Stupid, 1964 really was Peter Sellers’ seminal year: not only was he following up the success of his most popular role as Inspector Clouseau in the Pink Panther series’ second (many say even better) instalment, A Shot in the Dark. He also starred in Stanley Kubrick’s darkly satirical Dr Strangelove in no less than three separate roles, for which he would garner a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination.

Sellers had truly reached the pinnacle of his career as Britain’s foremost comedian, already having Ladykillers and Lolita under his cinematic belt, as well as an enormously popular career on radio and television shows. Despite remaining an enigma of a person throughout his career, it was his chameleonic talent as an actor and a great imitator that was now breaking onto the international stage.

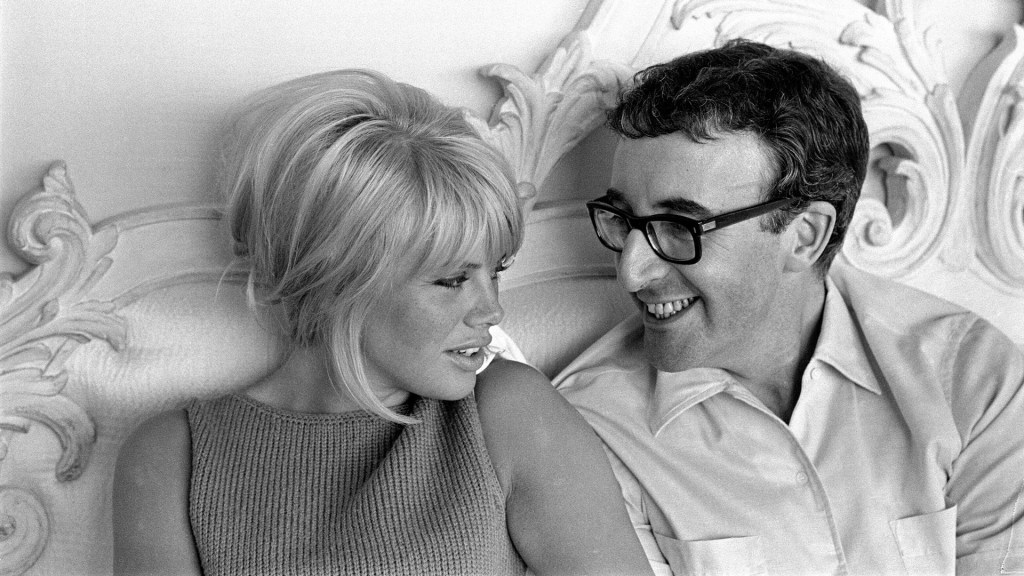

Propelled to such fame in 1964, Sellers also boldly stepped into another realm: a whirlwind second marriage. Having seen a photograph of an actress in a newspaper recently and finding out they were staying at the same hotel, Sellers simply sent his valet to her hotel room and a couple of days later, they were getting married. The woman in question was Swedish actress Britt Ekland, who had also just tiptoed into an early international career with the lighthearted western Advance to the Rear that same year.

Much has been speculated in the press about their relationship since, which was also the subject of The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, Stephen Hopkins’ biopic starring Geoffrey Rush and Charlize Theron in the respective roles. More clarity has been brought in 2020, when Britt Ekland herself opened up about their story, giving interviews for and around the BBC documentary Peter Sellers: A State of Ecstasy.

What stands out is the level of control that he exerted over her, from the decision to get married in the first place to exactly what she was going to wear and, of course, what roles she would play. Besides starring with Sellers in several films (After the Fox, The Bobo), his demands to be with her also led to her firing from Guns at Batasi, which damaged her budding acting career. Shortly after their marriage in 1964, Sellers suffered from a heart attack, whereupon Ekland was relegated to playing the caregiving woman at his side, making sure the star would get back to work.

Prior to the BBC documentary, Ekland had stayed notably vague on the details of their relationship, describing it now as an “atrocious sham” and Sellers as likely bipolar and a “tormented soul”, but also protecting herself and her daughter Victoria Sellers from the negative effects of the marriage. Divorce followed in 1968, after Sellers’ attempts to control Ekland as well as their constant fights became too much for her.

Their careers went in interestingly different directions. Sellers had difficulties moving beyond his iconic Clouseau role and mostly appeared in unevenly enjoyable Pink Panther sequels. He found more success on television (even an Emmy-nominated stint on the Muppet Show), before starring in what was arguably one of his best roles, gardener Chance in Hal Ashby’s wonderful political satire Being There (1980). Shortly after, Sellers died from another heart attack. His last Clouseau appearance was infamously made up of snippets from previous films in 1982’s Trail of the Pink Panther.

Ekland had arguably quite an interesting career, trying to both capitalise on and undermine her ‘Swedish bombshell’ image and distance herself from the yellow page presence she had endured at Sellers’ side. She starred as a burlesque dancer in William Friedkin’s The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968), as well as in a series of Italian genre flicks (notably as Antigone in The Year of the Cannibals in 1970).

The ’70s clearly provided various high points in her career, especially the lead roles beside Michael Caine in Get Carter (1971) and Lee Majors in The Six Million Dollar Man (1973). The folk horror classic The Wicker Man gave her an enduringly memorable appearance alongside Christopher Lee, followed by her turn (again with Lee, as well as Roger Moore) as leading Bond lady Mary Goodnight in 1974’s The Man with the Golden Gun. In spite of the film being seen as one of the weaker Bond entries, Ekland’s career had clearly reached its international height at this point.

One of the underrated highlights in her filmography to me is the lesser known Agatha Christie adaptation Endless Night (1973), with its wonderful mystery and Bernard Herrmann score. Ekland had clearly cultivated an interesting portfolio in British genre cinema, eschewing the fates of other non-English international actresses like Elke Sommer and Ursula Andress, who had never quite overcome their foreign accents and teutonic exoticism.

The yellow press caught up with Ekland, of course, when another whirlwind romance with Rod Stewart became public in 1975 and produced another string of salacious news stories. After a slump in her career during the 1980s, she later enjoyed quite a career on local British stages, especially in the 2000s, and she has appeared in various TV shows and interviews and has become a vocal contributor to her legacy as a regular social media presence.

As an ardent James Bond fan, I was of course always fascinated by the trivia that one of the actors to play Bond (technically Sellers played a version of him in the 1967 spoof of Casino Royale) had also been in a relationship with an actual Bond leading lady, but I was little aware of the difficult circumstances and the unpleasant amount of press attention this had drawn.

Decoding the myth of Peter Sellers and his comedic genius is one thing (our frequent contributor and film historian Johannes Binotto has found ingenious ways to do so in his essay “Peter Sellers: Always Undercover” (written in German) for a retrospective of Sellers’ work in 2016). Deconstructing the dynamics of the Sellers and Ekland Story is another fascinating subplot yet to be continued.