Every now and then I’m amazed at how pop culture doesn’t actually require you to have seen, read, heard or played something for you to have, or at least think you have, a fairly clear idea what it is. I’m sure I’ve seen snippets of versions of Alexandre Dumas’ Musketeers stories, but I don’t think I’d seen an entire Musketeers film – let alone watched a series or read any of the original novels – until a few weeks ago. (Not even Douglas Fairbanks’ silent-era original.) Nonetheless, I had quite a concrete image in my head: four friends in dashing 17th century outfits, wielding swords (but not muskets – go figure) and getting into swashbuckling adventures, rescuing damsels and foiling the wicked plans of scheming authority figures.

What I didn’t expect: that the three Musketeers (feat. D’Artagnan) would basically turn out to be The Beatles from A Hard Day’s Night… in dashing 17th century outfits, wielding swords (but not muskets – go figure) and getting into swashbuckling adventures, rescuing damsels and foiling the wicked plans of scheming authority figures.

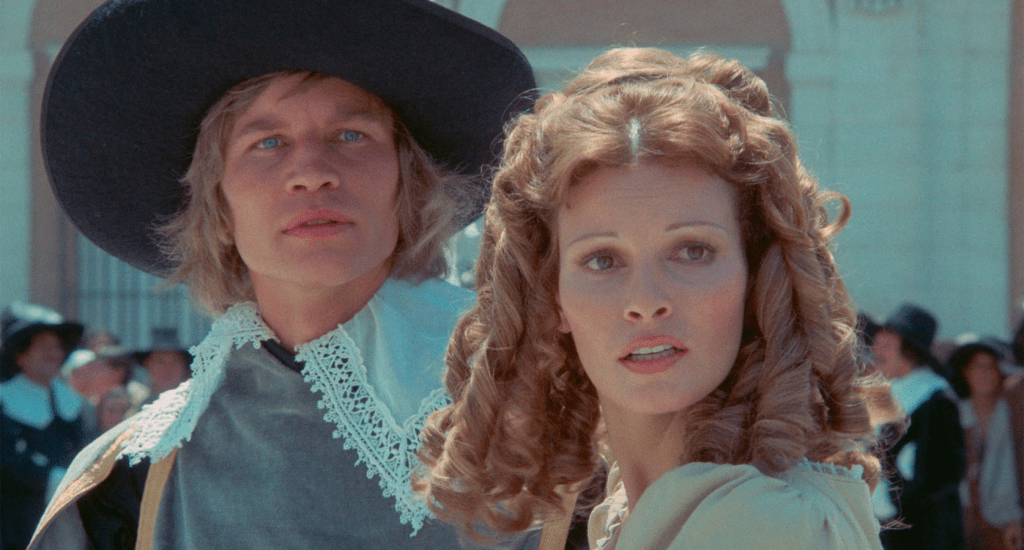

I went into these two films – which were originally filmed as one – expecting something much closer to the clichéd swashbuckler. What I got instead, especially with The Three Musketeers, is more akin to genre satire or even parody, as Lester never takes his characters, whether good or bad, and the world they inhabit altogether seriously. The title sequence is a red herring in this respect: it focuses on a shirtless D’Artagnan (Michael York, who works much better for me in comedic roles than in serious ones) fighting an opponent in what seems to be highly accomplished, energetic swordsplay. It’s the introduction of a ’70s hero – but it soon emerges that D’Artagnan is fighting his father, as the last lesson in his training as a swordsman, before the young man sets up for Paris to become one of the King’s Musketeers. However, already on his way to the city he finds himself insulted and knocked out by the man who will become his nemesis, the Comte de Rochefort (a dryly funny Christopher Lee), showing the audience that our protagonist, a country bumpkin of the highest order, is less of a hero than a fool. And his foolishness is soon highlighted even more as, once he arrives in Paris, D’Artagnan manages to insult the titular three musketeers, Athos (Oliver Reed), Pothos (Frank Finlay) and Aramis (Richard Chamberlain), one after the other, arranging for three separate duels on his first day in town. Hijinks ensue, as our protagonist first befriends the titular musketeers and then finds himself embroiled in a plot to discredit Queen Anne (Geraldine Chaplin), who is having an affair with the Duke of Buckingham.

Summarising the plot of The Three Musketeers, even if only briefly, highlights how messy and silly the story is – and I was surprised to find out that the script, adapted by George MacDonald Fraser (who also worked on Octopussy), hews closely to its source, which suggests that plotting may not have been Dumas’ greatest strength. But, at least in the first film, plot doesn’t really matter: as was the case with Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night, The Three Musketeers is primarily an opportunity for the audience to hang out with the four main character as they goof off. Tonally, the film finds itself somewhere between the aforementioned Beatles film, a Monty Python movie (Holy Grail or Life of Brian), and one of the better Carry On movies: whenever it has a choice between a silly series of jokes and a serious plot point, it will go for the former. And it works, mostly: The Three Musketeers doesn’t take itself seriously, and in the process it ends up tremendously amiable.

Except, that’s not quite fair: Lester and his cast and crew take the filmmaking seriously, and the film, with its gorgeous costume work, lighting and cinematography, sometimes looks downright painterly – except the characters in this painting are goofing off. It is also refreshing that Lester, helped by the script and the actors, rarely ever paints his iconic foursome as particularly heroic: D’Artagnan and the three musketeers are more likely to stumble or slip and lose their swords than to look like historical badasses, like John Wicks with swords instead of guns. The objective is for everyone, cast and audience alike, to have fun, not for the protagonists to look cool and infallible, which is both refreshing and charming.

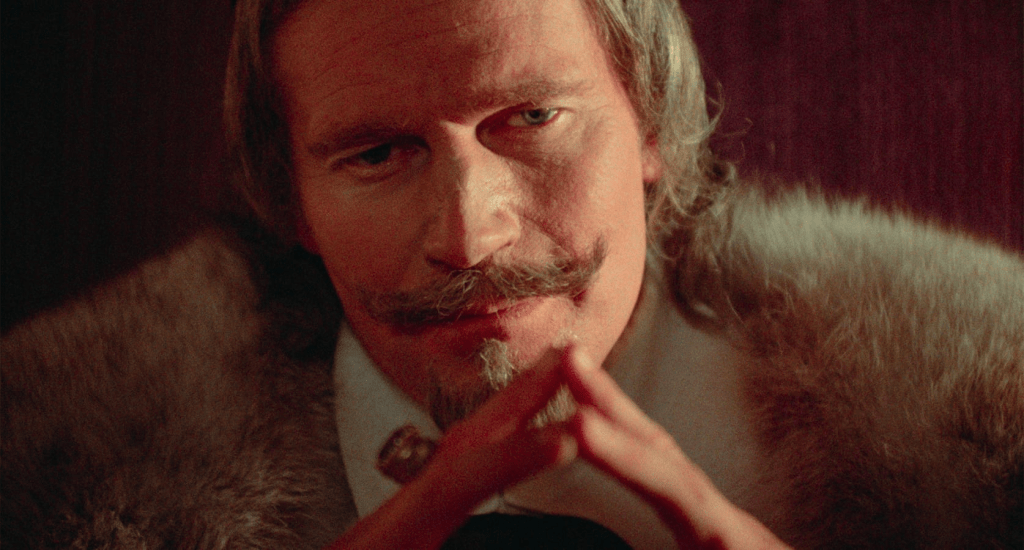

Verdict: I can understand why Richard Lester’s two adaptations of Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers is beloved of many. The films are goofy fun, but they are also crafted with a care that suggests the filmmakers’ more serious attitude at play. The cast is fantastic, even if some cast members are underserved by the script (in particular Richard Chamberlain, who probably has the least to do of the four protagonists), and the set of villains – Faye Dunaway as Milady de Winter, Charlton Heston as Cardinal Richelieu, and the aforementioned Christopher Lee – find the right balance between comedy villains and actual threats.

At the same time: while I enjoyed both films, especially the first one suffers from feeling, much like A Hard Day’s Night, as if it was made up as Lester and his cast and crew went along. Even a hang-out film like this benefits from more structure, as the string of goofy setpieces can begin to feel random – and never more than in an extended sequence in The Three Musketeers which appears to show D’Artagnan’s three friends die, one after the other, only for them to be alive and well ten minutes later after their young companion has completed his mission. This is not only straight from the novel, at least in terms of plot, it also makes for a good surprise joke – but it scuppers any sense that our heroes might actually not get out of this alive, undermining the sense of thrill. That’s obviously fine for the Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night, but in a swashbuckling adventure, well, it rather saps the adventure. But even if The Three Musketeers is seen purely as a comedy with the occasional sword fight, its shaggy looseness results in the film feeling strung together haphazardly, like a story told by a four-year-old retelling a film half of which he’d slept through: this happened, and then this other thing happened, and finally this happened. It almost makes me think that the first film might work best as a sort of stoner comedy, albeit one set in the 1600s.

Considering that The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers were based on a single novel and filmed as one movie, turning into two features only when the producers realised that there was too much material to make this a roadshop epic including an intermission, the extent to which the second film eventually changes tack is quite striking. It starts off as the same kind of amiable, goofy hangout flick, and indeed, some of the best jokes and setpieces are in The Four Musketeers – but roughly at the halfway point it feels as if Lester and his writer Fraser suddenly remembered that Dumas didn’t write a comedy: and while the filmmakers still do a good job with the part of the film that’s more of a straight-laced swashbuckling adventure, with actual stakes, it is exactly the goofy, shambolic nature of what has come before that undermines what the movie sets out to do at this point. After seeing Athos, Portos and Aramis seemingly die and then shake it off, like kids playing at musketeers, how are we supposed to take later deaths seriously? Why is it any different when this characters gets skewered than when another character got a sword through the neck in the previous film? It would certainly not be impossible to tell the story as one that begins as goofy farce but then turns into thrilling epic with a tragic edge – and I suspect Lester, who blended and shifted tones beautifully in his bomb-on-a-cruise-ship film Juggernaut, would have been up to the task -, but instead we’re left with a disorienting tonal needle scratch that feels too random to fully work.

Nonetheless: if Richard Lester’s original two Musketeers films don’t quite work for me as a whole, there is a lot here to like, from the playful hang-out humour and commitment to subverting the macho heroics of the protagonists to the sometimes startlingly beautiful cinematography and wonderful production values that commit to creating a complete, if often goofy and sometimes absurdist, world (the chess game played with dogs!). Just don’t go in expecting a truly thrilling adventure, because that’s not what the films aims for to begin with or deliver consistently once they change tack: this is closer to a Christmas panto that commits to the bit, being frivolous in terms of its story and characters, and serious in terms of wanting to look and sound its absolute best. The heroes are fun, the side characters colourful, the villains worthy of being hissed and booed. I imagine this set of films is perhaps best enjoyed after a rich Christmas lunch and a few glasses of wine, so it doesn’t matter if telling a fully coherent story isn’t really on the menu with this one. Perhaps if Lester had been more interested in something more tonally coherent, the two films would instead have lost what makes them what they are. Let others make a straight-laced adaptation.

The gorgeous Faye Dunaway was incredible in this

She certainly got the balance right between panto baddie and a more rounded villain. ’70s Dunaway rules.