Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

At the beginning of the 2024 Laurent Bouzereau documentary Faye, viewers might be forgiven for thinking we’re in for 90 minutes of diva-ing. With some justification, this is about Faye Dunaway after all, and she is one of the greats, but also has a bit of a reputation. “Can we shoot?”, we hear Dunaway insist impatiently, in voice-over as the camera moves through New York’s famous cityscape: “We need to shoot. I’m here now. Come on!”, before we get the first shot of her face. Her expression softens perceptibly after it’s confirmed to her the camera is rolling. Later, we see her fidgeting in her seat, finicking with her hair, and being – let’s be honest – rather demanding. “So now you see what it is. About me.”, she quips finally. “Not easy.” Her diva-ing, however, is not the film’s ultimate focus. What we get is, in a way, a life in pictures. We see her as a very young girl (Dorothy Faye Dunaway, as she was then), we see her at college age, we see her mom, her dad, her siblings. But that Dorothy Faye, although she is “integral” to the Faye we’ve come to know, is not the current Faye, at least that’s how she sees it. Faye is the persona she created, insists the famous actress. All the more fascinating, then, to go back to how she grew up, as it clearly had an enormous influence on her, and she seems to have a great deal of fun reminiscing.

As her father was in the army, she led the kind of peripatetic life associated with that. Her mom was the kind of strong character that, in her words, took “things into her own hands when they didn’t work” – something Faye very clearly took to heart and acted on. The travelling was “painful,” she says, because you have to leave everything behind. And judging from her relationships (she later muses that even those seemed to come and go in similar two-year cycles), that stuck with her as well, for good or ill. It didn’t help that she was also a child of divorce. She made her way to Boston University, where she learned her craft and perfected it under Elia Kazan. He was able to “locate the part in the actor”, according to the actor, director and writer Barry Primus, who was in the same troupe. Faye herself insists on a good education and an exacting work ethic to be successful in the industry. She’s also a stickler for detail. You do not get to be one of the greats by accident. That she is one of the greats, and why, is undeniable. But her openness in this doc is very striking. And her frankness often approaches something akin to wisdom. She speaks of her bipolar diagnosis and her struggles with substance abuse. It’s not an excuse: she’s still responsible, she insists, but these things are an unavoidable fact of her life. She is matter-of-fact about the criticism that she sometimes walked around in “a cloud of drama”. But by and by, we get the sense that her reputation for being “difficult” was not, generally speaking, due to her struggles with mental illness. Demanding, yes. A perfectionist, yes. But actresses clearly were supposed to be a certain way (mainly very, very thin), and what with actors was “artistic temperament”, for women was quickly seen as “difficult”. To the surprise of absolutely no one, incidentally. Although I have no doubt she really could be difficult. So are most people who work themselves half to death, demand perfection from themselves, struggle with their own personal difficulties throughout, and all the while, fans demand the perfect idol, not messy humans. All of which she aimed to deliver. It was not by mere chance, then, that she also managed to land absolutely fantastic parts for herself.

In the ’60s, when cinema demanded more freedoms after the Production Code crumbled, she was in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), winning the role over stars such as Natalie Wood, Jane Fonda and Leslie Caron, no less. It made her into an icon. Success, she says with some justification, is freedom. And so she got to choose parts such as Diana in Network (1976). But also Joan Crawford in the barely watchable (its camp credentials notwithstanding) Mommy Dearest. Whether it was down to the director, or the timing, or just Faye herself: it is often cited as having been career-ending for Dunaway. And perhaps it was for a short while. But there’s something to be said for the argument that artists such as Faye just didn’t have a real place anymore in Reagan-era cinema. The paradox of being an icon, on the one hand, and incredibly subversive on the other, just didn’t play anymore. Add this to the fact that, as women get older, parts dry up: and so it was time for something else. As is her custom, she simply kept working. TV (she co-starred in a fabulous 1993 episode of Columbo: All in the Game), theatre, directing, whatever there was that she thought she could do.

Her son has a big part in this doc, which makes a lot of sense, but he also gives the impression that he’s parroting certain fashionable talking points. Things such as Faye’s bipolar and her depression being part of what makes her great – something Faye herself half-contradicts: “The better you feel”, she opines, “the more you are able to do work that is meaningful.” Which seems to me a very constructive and much healthier attitude, and one that dashes the kind of mythmaking that accompanies stars like her. It shows great clarity – and she’s right. Kudos for not perpetuating the tortured artist myth, not even when it might enhance her mystique. And while the film certainly slants towards Faye Dunaway not merely enacting, but embodying her parts, it gives also the impression, almost despite itself, that it’s rather the other way around. She creates her parts through hard work and a great deal of courage, and infuses them with something uniquely her own. Contrary to the expectations set by the film’s beginning and perhaps the expectations evoked by the kind of grande dame we’re dealing with, clearly we do not just get the persona. The “role” of Faye playing Faye. There is a bit of that, but on the whole, I found it disarmingly frank and unexpectedly revealing. We’re getting a great deal of common sense, very little self-dramatization, and some genuine mythbusting, even if the myth is her. “Foolish girl,” she laughs at herself when she addresses the much talked-about relationship with Mastroianni, “it was illusional. Delusional, perhaps.” Even if he was, she adds almost casually, the love of her life in a way. A very insightful documentary and certainly worth a watch, for anyone interested in the time, the films, or the absolutely fabulous Dunaway herself.

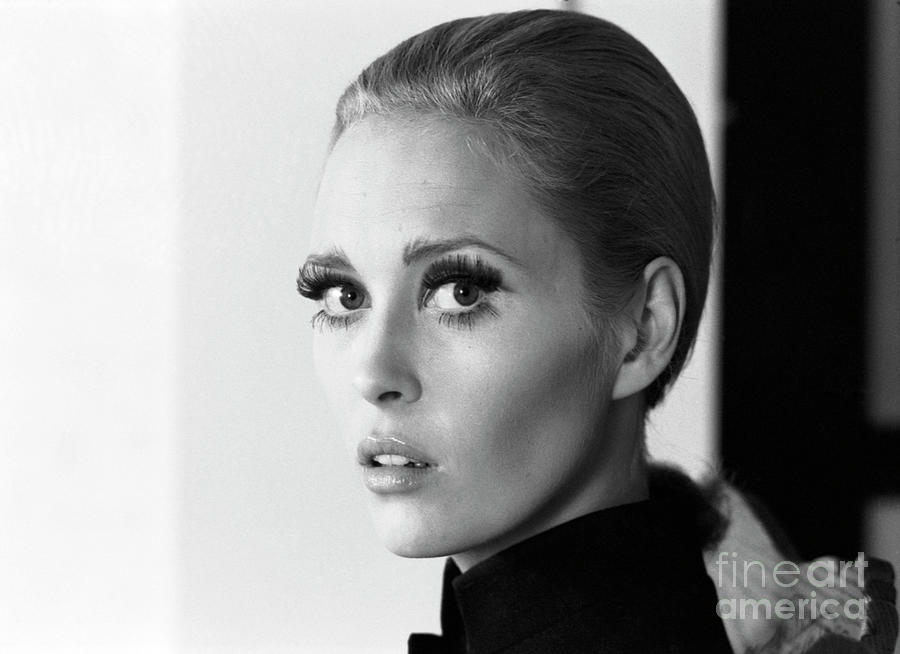

Most beautiful woman of all time