Melanie’s review of 1980s cult musical Little Shop of Horrors through teenagers’ eyes finally gives me a chance to loop back, not only to the 1960 original directed by Roger Corman, but also to the director/producer himself, who arguably became one of the greatest masterminds of copycatting any movie hit within his own production universe. Roger Corman was running his own, wildly successful shop of horrors – actually a big, bold, fiercely independent venture of horrors, thrills, and other exploits!

My fascination with Corman began back in 1998 at the Locarno film festival, where director Joe Dante was honoured for his lifetime achievement. Alongside the world premiere of his latest film Small Soldiers, there was also a broad retrospective of his earlier work as one of the “Corman Second Generation” of filmmakers who had been discovered and given their first chance by the producer. Dante, of course, was there in person for me to see, but he had also brought along some of his closest collaborators: actors Dick Miller (to be spotted in practically all his movies) and Barbara Steele (the British queen of horror), as well as Roger Corman himself. Needless to say, I snatched autographs from all of them!

There was a broad selection of almost one hundred films in the retrospective, from arguably Corman’s most productive period, his New World Production ventures of the ’70s and early ’80s. I particularly remember being awestruck by Sam Fuller’s White Dog (1982), gobsmacked by Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000 (1975), intrigued by Dante’s Innerspace (1986), amused by Corman’s own The Terror (1963) and, of course, his original satirical Little Shop of Horrors (1960). Dante’s The Howling (1980) was another astonishing horror feast made on a shoestring budget but still looking truly impressive.

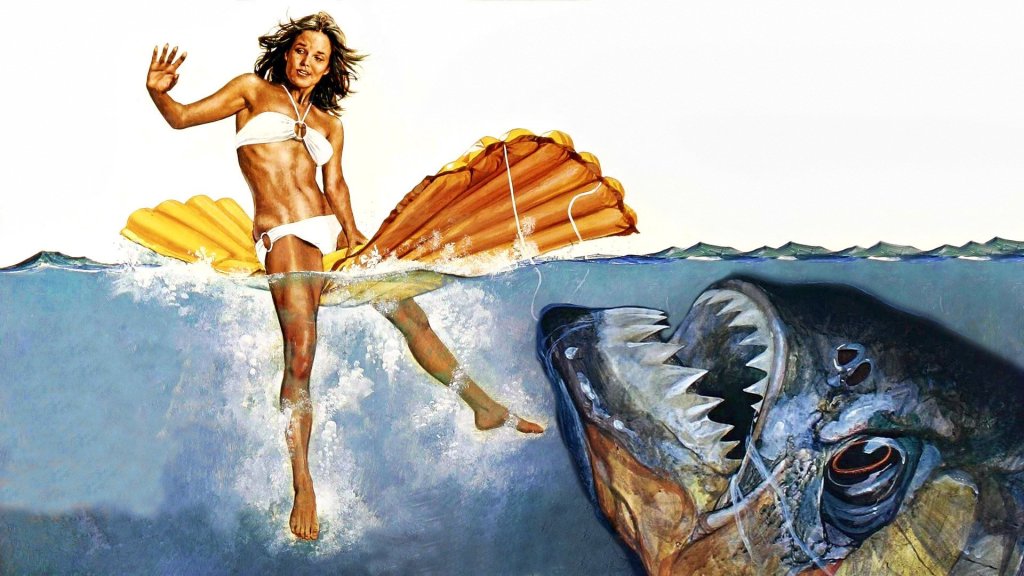

My biggest highlight, however, was seeing Dante’s Jaws-inspired rip-off Piranha (1978), such a wonderfully clever variation of water terror with its Watergate-style government villains (the original Body Snatchers’ Kevin McCarthy alongside Steele and Bartel) and heroes against their will (Bradford Dillman and Sound of Music‘s Heather Menzies). The cheap piranha effects were laughable, but there was something appealing in its biting satire, its measured suspense and the otherwise admirable production values, including a highly atmospheric and eerie score by Pino Donaggio (Carrie, Dressed to Kill). Despite its obvious flaws, I immediately felt its cult status and the film lovers’ effort put into it.

Dante, Miller, Steele and Corman happily answered questions after the screening and I was impressed not only by their happy recollections but by the gentle presence of Roger Corman modestly recounting the production history and feeling flattered by the honours bestowed on the film, Dante and this second “Corman generation”. Little did I know at the time what a father figure he had already been to so many other first-time directors, actors and other filmmakers: Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, James Cameron and Jonathan Demme (among many others) all started out under Corman, while Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, William Shatner, Diane Ladd, Charles Bronson and Bruce Dern launched their acting career in various films of his .

Corman himself started out as an independent producer in the 1950s after working his way up as a messenger at 20th Century Fox and soon became a story reader, recommending scripts for production. His astute sense for marketable material and his willingness to work for free for the experience soon landed him production opportunities and often uncredited directing gigs. He had a keen sense for tight budgeting and an instinct for exploitable fare. His production and direction credits included the original Fast and the Furious (1954), as well as salacious fare like The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), Swamp Women (1956) and Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957). All of them were extremely cheaply made and all of them made a big profit. Famously, Corman claimed that among his sixty films as director and his over four hundred (!) films as producer, none ever created a loss.

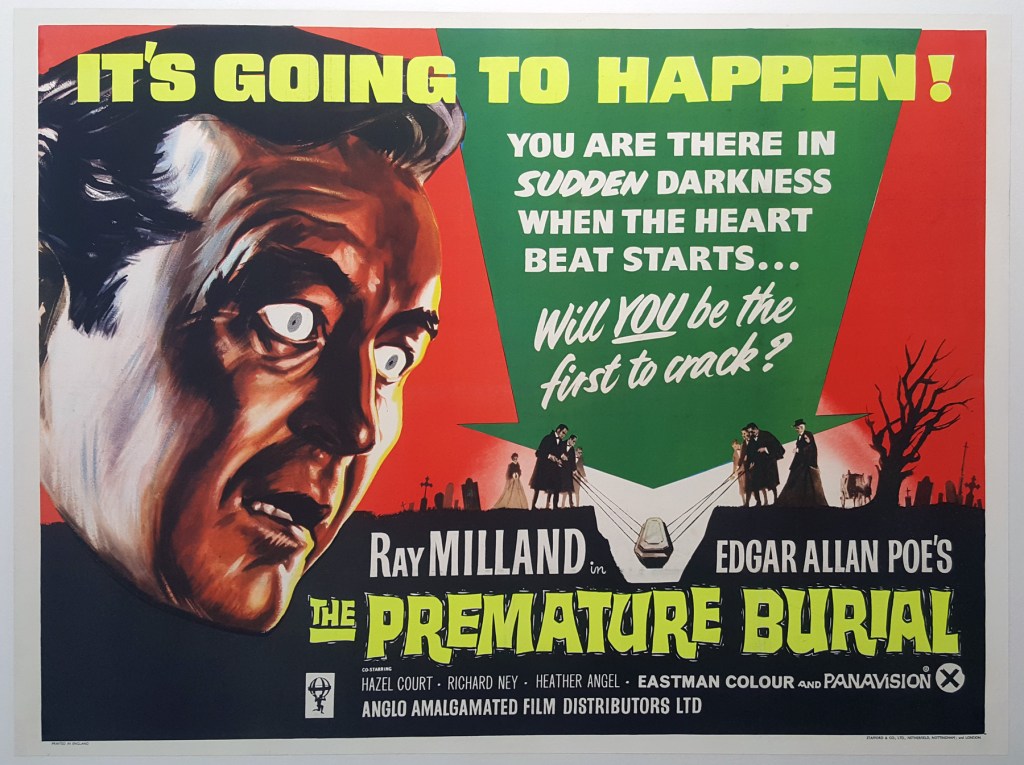

When my dad was brought down by a bad pang of rheumatism in 1990, his only joy was staying awake through his pain watching Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adpatation on Sky TV: The Fall of the House of Usher, The Pit and the Pendulum and The Premature Burial starred memorable actors like Vincent Price and Ray Milland and transported Poe’s night tales into claustrophobic studio interiors. Corman’s thriftiness now made for valuable cinema and great entertainment. The Raven and The Terror (both 1963) starred Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre and Jack Nicholson and made for fabulously atmpsheric midnight cinema. He found partial recognition from critics for his portrayal of racial violence in The Intruder (1963) and the pre-Easy Rider cult film The Wild Angels (starring Fonda, Bruce Dern and Nancy Sinatra), but his focus remained making a big buck for his exploitation movies.

His work for American International Pictures came to an end when he founded his own New World Pictures in 1970, ushering in the phase honoured by the Locarno film festival edition I attended. The titles became even more salacious now: Angels Hard as They Come (1971), Night Call Nurses, Women in Cages (both 1972), Boxcar Bertha (directed by Scorsese!), Big Mad Mama and Crazy Mama (starring Angie Dickinson and directed by Demme). During its peak, New World’s biggest hits included Death Race 2000, Cannonball, Death Sport, Grand Theft Auto (inspiring the later popular video game series), Piranha and Battle Beyond the Stars, all of them trying to capitalise on a previous horror, sci-fi or fantasy hit but still adding something interesting to the mix, assuring their later status as cult favourites.

It’s easy to overlook some other commendable ventures Corman followed, for example distributing international films like Bergman’s Cries and Whispers, Truffaut’s Story of Adèle H., Schlöndorff’s Tin Drum or Fellini’s Amarcord to US cinemas. His later Millenium Films and Concorde Pictures productions during the ’80s and ’90s were less successful but no less profitable and numerous and his return to directing included 1990’s soon discarded Frankenstein Unbound and an abandoned Fantastic Four adaptation in 1994. His name was later given to many of his productions with “Roger Corman presents” and his face can be seen in many of his prodigy’s biggest hits, including as a senator in Coppola’s The Godfather Part II and as the FBI director in Demme’s Silence of the Lambs.

At the time I encountered him in Locarno, he had just picked up another honorary award at the Cannes Film Festival for his life achievement and he would still go on to direct and produce many movies. His lasting legacy was also assured by documentaries tracing his enormously productive career and while he saw himself as a mediocre figure at best by comparison to others, his profile has only grown in stature. 2021’s Roger Corman: The Pope of Pop Cinema by French director Bertrand Tessier shows him beaming at his long career and the influence he has had in helping so many filmmakers along the way getting their start in Hollywood. As one of the truly independent producers and directors, he’s had few missteps and the image of a determined yet gentle wizard of unashamedly exploitative cinema prevailed.

Corman passed away in May 2024 at the age of 98 – no premature burial at all!