One of the things that video games can do magnificently is create worlds. These posts are an occasional exploration of games that I love because of where they take me.

In 2017, a small Australian studio called Team Cherry released Hollow Knight. The game, an action adventure set in a world of insects, was well received by gamers and critics, and its reputation grew over the following years, as much for its challenging gameplay as for its melancholy world and atmosphere. Over time, Team Cherry aded to the game in various ways game – but the main expansion they originally promised, which was to feature Hornet, one of the game’s characters that starts off as an antagonist only to become an ally of the player character, proved too ambitious. As a result, Team Cherry announced in 2019 that Hornet’s adventures could not be contained in an add-on of the original Hollow Knight but instead required their own game: Hollow Knight: Silksong.

It would take another six years until Silksong came out.

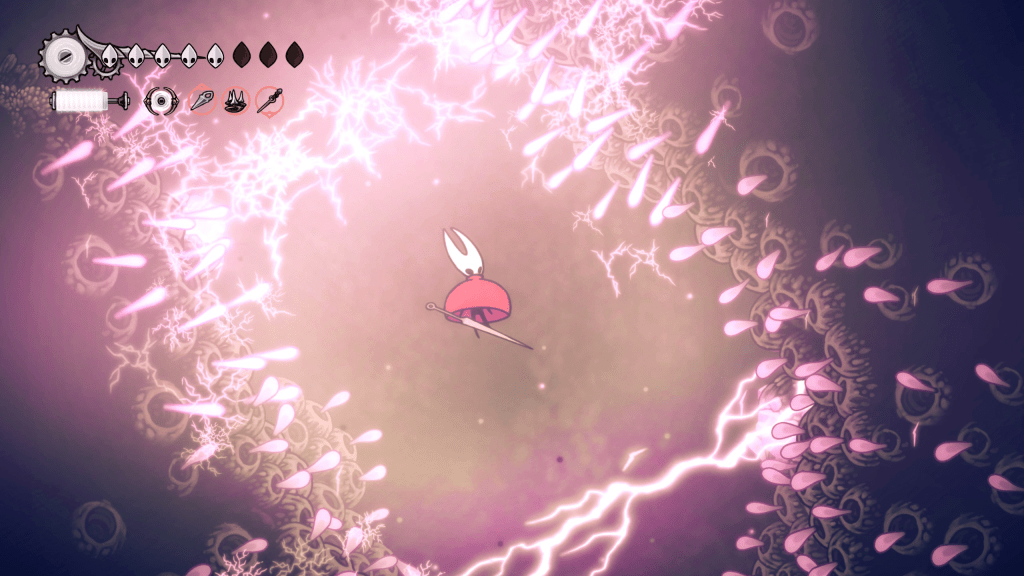

For the last few months of 2025, I played little more than Silksong. In part, this was because the game was huge, featuring an expansive world (even if still set in a miniature realm peopled by sentient bugs) with a large number of environments, characters and enemies. However, the main reason why I played Silksong for over 80 hours was its difficulty: the game is often punishing, and many of the newcomers who’d heard great things about Hollow Knight, itself not an easy game, found that Team Cherry’s design ethos could at times be described as almost sadistic. This is perhaps illustrated best by the following example: one particular bench (with benches being sanctuaries of sorts in most of the game), positioned after a particularly challenging stretch, turned out to be booby-trapped, smashing the unwary player sitting down expecting it to be safe. There are in-game justifications for this, and the trap can be defused, but still: oof.

While I’ve been playing video games for over 40 years, I’m by no means great at games, especially those requiring nimble fingers. I am stubborn and patient, though, and willing to replay parts of a game over and over again if the game feels reasonably fair and if I can tell that I am generally getting better at a certain challenge. (Try again. Fail again. Fail better.) But I don’t think that these are the main reasons why I stuck with Silksong, in spite of dying over and over, and over and over and over and over, to its many platforming challenges and boss enemies. No, the reason why I didn’t give up on the game is that, both in Hollow Knight and Silksong, Team Cherry have excelled at vibes.

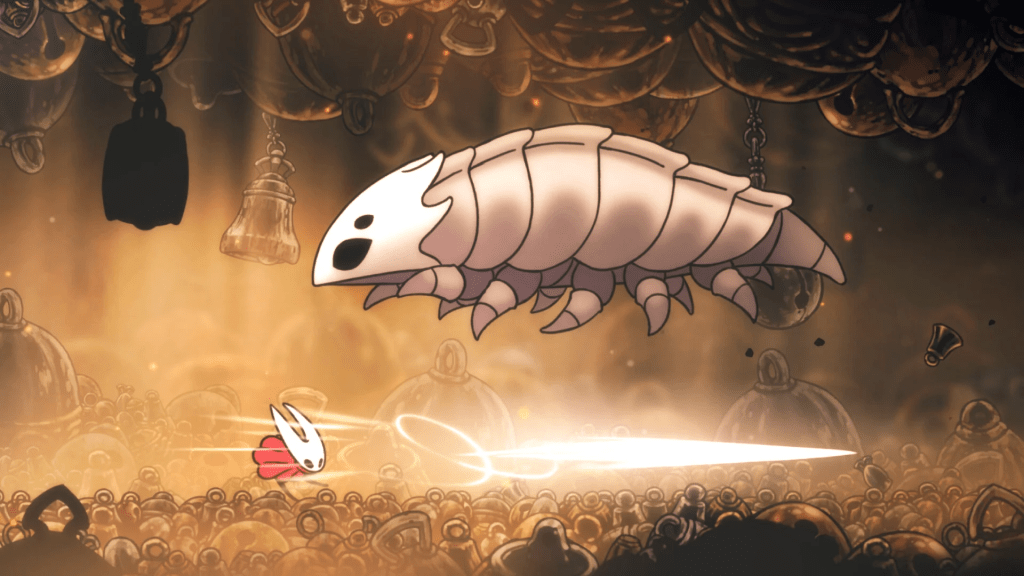

In terms of genre, both of the games can be described as Metroidvanias, which (for non-players) basically means that they feature a sprawling, interconnected world, many parts of which are gated behind abilities that the player acquires. Typically, this might mean that in the subsection of the game world that is immediately accessible, the player might find an upgrade that allows them to dash across gaps or cling to walls or jump twice to achieve greater heights – and this in turn opens up parts of the map that were previously inaccessible, and there the player would find yet other abilities and upgrades.

Metroidvanias are typically very ‘gamey’ games: the genre has clear rules and mechanics that players will find in most Metroidvanias. One might think that this focus on gamelike structure and mechanics would make it more difficult for the player to buy into the world and the fiction that a game portrays. Silksong isn’t split into levels (as most Super Mario games are, for instance), but its various interconnected locations are rooms with distinct combat and platforming challenges, and while Hornet doesn’t come with the lives of early games, she dies and respawns, as is typical for characters in video games. On one level, there is something very mechanistic to both Hollow Knight and Silksong – and to most Metroidvanias: do A, get object B, which opens door C, behind which there is enemy D, which, once beaten, bestows ability E on the player. The many, many repetitions of these structures resulting from players like me dying easily and often only serve to make them more obvious.

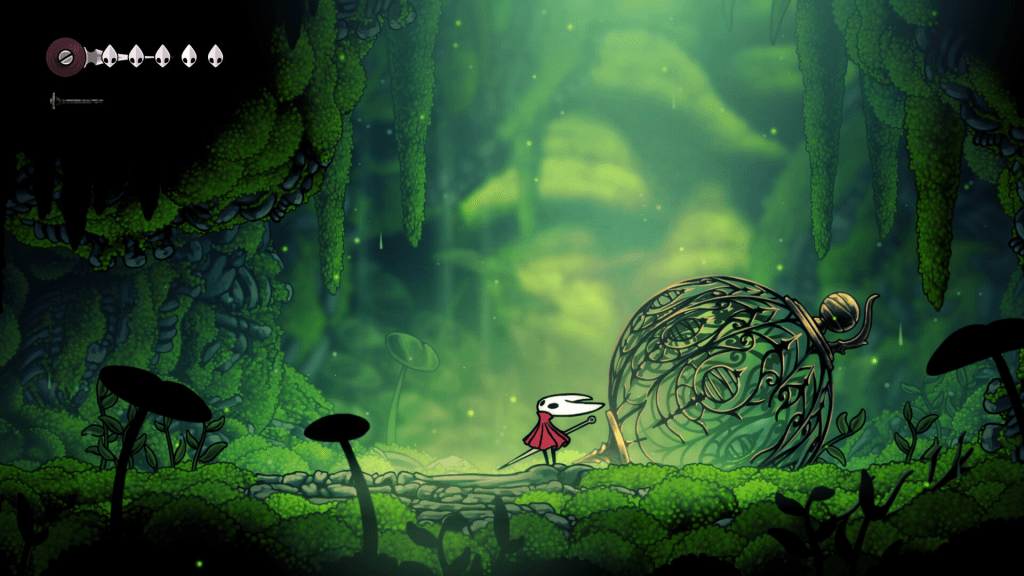

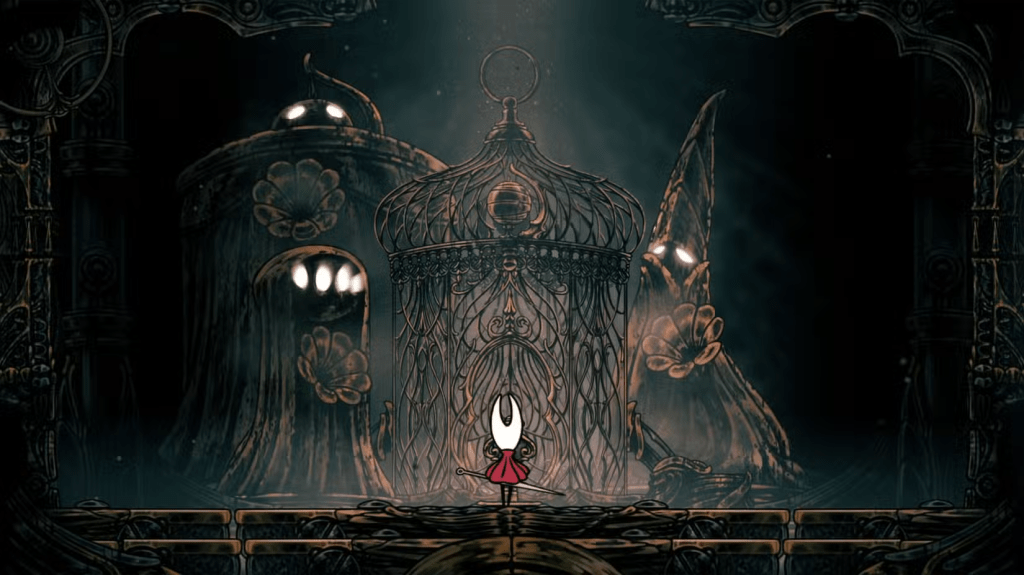

And yet: in both Hollow Knight and Silksong, I feel like this is a real world, these are real, albeit insectile, characters. There is a sense of history and weight to Pharloom, the doomed realm in which Silksong is set, and those that inhabit it, from its godlike queen and its distant, aloof ruling class to its workers and the many pilgrims that try to make it through a forbidding world that’s out to get them in one way or another.

Obviously, the beautiful 2D art of the game has a large part in this, as does the elliptic, evocative writing: differently from so many video games, especially ones that pride themselves on their worldbuilding, neither Hollow Knight and Silksong favours the exposition-dump style of storytelling, instead insinuating and hinting and filtering its information through characters with their own perspectives and agendas. But, as much as these, it is the music written for the games by Christopher Larkin that gives their world and characters personality. Check out the three examples below: the tune written for Bone Bottom, a forlorn location early in the game peopled by insects at the onset of their pilgrimage to the Citadel of Pharloom, whose inhabitants try to forget that their journeys are as likely to end in death as in enlightenment; the music of Bellhart, an outpost halfway to the Citadel built around numerous bells; and the melodies of the Choral Chambers, a haunting place of gold and silk. There is a whimsical, Danny Elfman-like touch to some of Larkin’s music, which in Silksong is complemented by an ethereal sadness not unlike that of Thomas Newman’s best scores – but in all of this, the composer’s work never feels derivative but entirely of a piece with the world Team Cherry has created.

But while much of the music for Silksong evokes a vibe, Larkin does not shy away from more theatrical pieces – such as in the tune that accompanies the balletic fight against the Clockwork Dancers, two automatons that, over the course of the fight, reveal a pathos powering one of the most poignant moments of Silksong.

When I finished Silksong during the Christmas holidays, I was relieved in part, and glad to have made it through its gruelling final battles. But I also missed being in Pharloom, and that sense was fuelled mostly by Silksong‘s music and its uncanny ability to tie everything together: the game’s Metroidvania structure and mechanics, its art that succeeds so well at being cute, melancholy, grandiose and intimate, its world, story and characters. Listening to Larkin’s score is more than just returning to music I like: it brings back the feelings I had while exploring, liberating and dooming Pharloom. And, as with Hollow Knight, it will be the music that ends up pulling me back there to replay Silksong.