Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

Time loop narratives are almost always power fantasies. Sure, there’s a comical element about them, but that’s part of the fantasy: the protagonists of time loop stories are caught in an existentialist Looney Tunes short, but whenever they step on a rake or have a bomb blow up in their faces, they go back to start with added knowledge: if they cut this wire instead of that one, if they push this button rather than pulling that lever, if they jump to the right two seconds after they hear the car horn, they’ll survive. And thus, step by step, they master their situation.

In that sense, time loop narratives are the kind of power fantasies that are typical for video games.

From the beginning, video games have been about trial and error: play again, and this time you know how to react. You know that the enemy ships will come from the left and move to the right – so you position yourself just so, push the fire button, and blow them all up, one after the other. And that’s what time loops do, whether you’re Groundhog Day‘s Phil Connors or Edge of Tomorrow‘s William Cage: they let you Live, Die, Repeat. They let you fail, then reload, try again and, perhaps, fail again, but definitely fail better. It’s no coincidence that one of the main characters in Reset, which Melanie wrote about last week, is a game designer, because a time loop is quintessentially like a video game – so who better to understand and then beat the puzzle than someone who designs games?

It’s this power fantasy that lends a time loop its sense of fun: even if you die, repeately, in more and more outlandish ways, you don’t really die. You come back, armed with the foreknowledge of what will happen. And they even allow for frivolous experimentation – what better opportunity than a time loop to find out what it’s like to bungee jump, sky dive, seduce that cute barista? Which, again, is very much like video games, where you might save in order to try something outlandish – and if you die, you just reload. Sure, at times the characters in time loop stories may feel like Sisyphus, pushing that boulder up that hill yet again, but the existentialist dread of being stuck and repeating your mistakes over and over is a tangent: time loops are puzzles that can be solved.

Warning: spoilers ahead for the film 12 Monkeys (1995) and the video game Outer Wilds (2019).

Except when they’re not. 12 Monkeys is a time loop of sorts, but a closed, deterministic one: young James Cole sees his time-travelling future self get gunned down at an airport, but he cannot learn anything from what he sees, and Cole is doomed to live, and die, the way it has always been. We think: this is Bruce Willis, the living, walking power fantasy of the ’80s and ’90s. If anyone can stop the apocalypse before it happens, he can, right? But no: as the tagline for 12 Monkeys says, “The future is history”. Loops require wheels and cogs, and these cannot do anything other than turn in circles, arriving where they started and doing the whole thing all over. In this take on the time loop narrative, the loop isn’t a chance to do things over, to fail again and fail better until you succeed. Instead, it is a wall that you keep running into, Looney Tunes-style, as the laugh track sounds more and more hollow with every spin on the wheel.

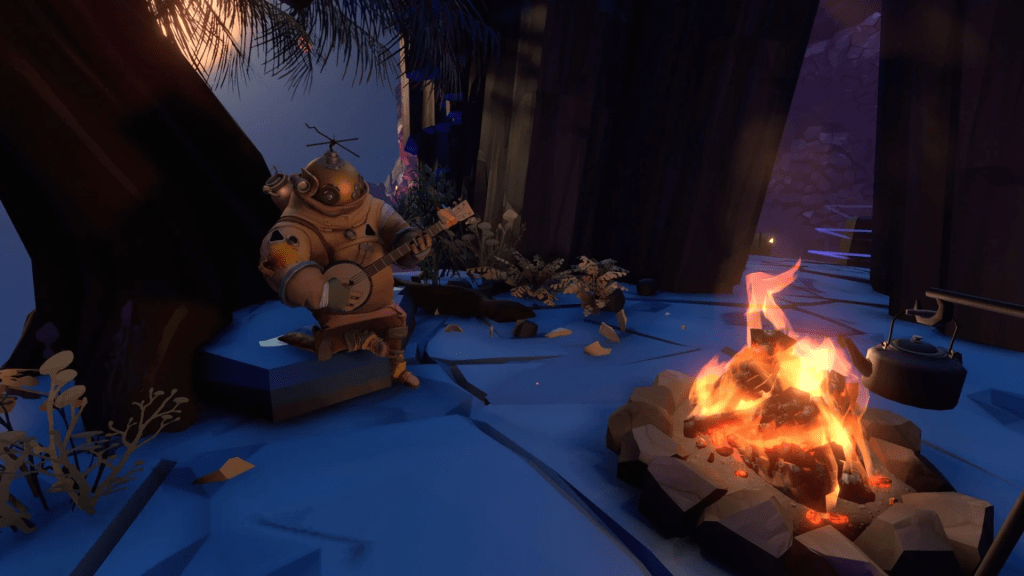

And then there is Outer Wilds, perhaps the best game yet made using a time loop. In it, you are a space explorer setting out in a ramshackle little ship on their first flight. You take off and head towards one of the nearby planets and moons: perhaps Giant’s Deep, the one made up of mostly water and buffeted by violent storms? Perhaps the Hourglass Twins, the binary planets that, like galactic tides, transfer sand from the one to the other as they orbit each other? Or Brittle Hollow, which has a black hole at its core, causing it to collapse in on itself? Just make sure to make up your mind soon, because, as you find out on your first sortie, 22 minutes later your world ends, as the sun goes supernova and the expanding wall of plasma destroys everything, including you and your ship. Boom, snooze, repeat: you wake up at the campfire where you dozed off before boarding your ramshackle little ship and taking off on your first space flight. What may expect you out there? Six planets, several moons, a comet, and a sun that, 22 minutes later will go supernova, destroying everything.

So, as the gamer of many years that I am, I assumed: this is a time loop in a video game. Obviously, through trial and error, I am meant to find out what causes the end of the world – and then prevent it from happening. Ever since booting up that Commodore 64 in the mid-’80s and loading my first game, I’ve saved countless worlds and civilisations. Why should I expect this adventure to be any different? Except, no, that’s not it. The moment Outer Wilds begins its loop, its ending has already been determined. It’s like a fuse has been lit, except it’s a fuse that is as old as the universe. The loop isn’t designed to break this, it isn’t a power fantasy that ends with you saving everything: it’s there to help you understand. You can escape the end of the world, but the world still ends. And all you can do is bear witness. And, if you’re lucky, roast a marshmallow.

The older I get, the less I find myself interested in power fantasies, and the more I appreciate time loops that tell a different story: not the puzzle box of finding out the what, how and why of the loop, of solving the puzzle and ending the loop, but instead stories that ask questions about the extent and limits of our agency, and how we live with these. Sure, I can see the fun and excitement of imagining yourself to be Phil Connors, becoming a better person and getting the girl (and learning to play the piano!) in the process, or becoming one of the heroes of Edge of Tomorrow and defeating the alien invaders after many, many thrilling loops. But these days I find it easier to think of that guy in ancient Greece (okay, technically in the underworld) pushing a boulder up a hill. For the first several millennia, he probably fantasised of finding a way out, finding a solution, the right sequence of actions that would free him forever. But, by now, perhaps he’s found that the way out is a different one indeed.