Here’s how you make a Brazil: You start with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, the iconic dystopian novel about totalitarianism and mass surveillance. You mix this with the monumental aesthetics of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Blend in some Franz Kafka, ideally The Trial. For flavouring, add a healthy dollop of Monty Python’s Flying Circus and a pinch or two of Federico Fellini and Jacques Tati, and finally sprinkle the resulting mess generously with bureaucracy. As the waiter might say: Monsieur, Mesdames: Bon appétit!

Brazil‘s influences are unmistakeable, and perhaps that was in part what drew me to the film when I first watched it in my mid-teens. I’d read Orwell’s classic, I’d seen a bunch of Monty Python sketches and films, I’d read some Kafka at school. For Brazil, Terry Gilliam took all of these and remixed them, so that the end result felt not so much derivative as inspired – but still perfectly recognisable for a teenager heavily getting into film and literature, and Brazil made me feel smart and knowledgeable for recognising these influences. Gilliam’s carnivalesque irreverence definitely helped, but I clicked with his style and tone much more than I had when I first saw Time Bandits, which I found visually fascinating but also quite obnoxious, possibly because I didn’t see that one first when I was a kid. As someone in the latter half of his teens, I found Brazil‘s Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) much more relatable: he’s something of a nebbish loser, but he’s also a dreamer with the potential to become more than he has allowed himself to be.

What perhaps keeps Brazil most from feeling like a knock-off of the works that inspired it, other than its art direction, is the way Gilliam and his collaborators, first and foremost his co-writers Charles McKeown and Tom Stoppard (yes, that Tom Stoppard!), replaced the totalitarianism (fashioned largely on communism under Stalin, but made into something more recognisably British by Orwell) with an ultra-bureaucracy, where every aspect of society is ruled by systematic inefficiency: official channels, forms, processes that loop back on themselves. It’s what gives Brazil its satiric edge – it’s no surprise that the film is much funnier than Orwell’s novel, but Gilliam is committed to exploring his dystopia shaped in equal parts by bureaucracy and capitalism (it’s not as foregrounded as the former, but neither is it particularly well hidden) to the bitter end.

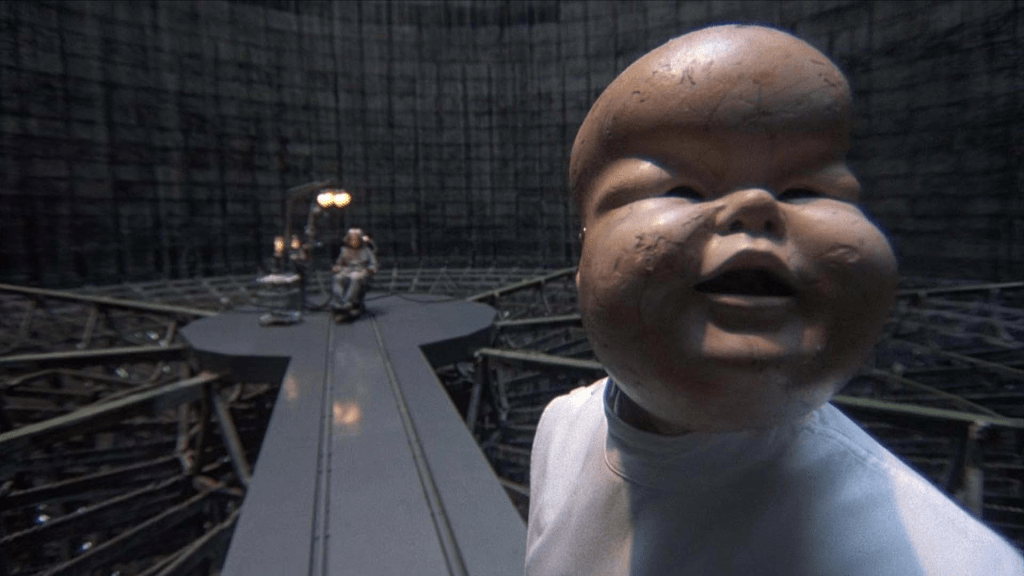

It is this tonal range that remains the most striking, even on revisiting Brazil after not having seen it for a while: although the film starts with an explosion (a terrorist bombing, or just the inevitable result of a system that’s on its last legs, and a bureaucracy that makes it impossible to repair anything without a signed form 27B/6?), much of its first half or so is funny – you may not want to live in this world, but it is amusing to visit, with a whimsy that isn’t miles removed from Aardman’s Wallace and Gromit films. Except hints of the darkness underlying the absurdist silliness are never far away, and as the film proceeds, they tip the darkly irreverent humour into something much more desperate. This is a world where a fly falling into the literal machinery of the state can result in the death of an innocent man – not so much because the state is out to do evil, but because it doesn’t care to keep itself from doing evil, because there’s no need. No single cog in the system is considered culpable, because it is finally the interplay of all of them that dooms poor Archibald Buttle, shoe repair operative. The hints of the darkness, the rottenness at the heart of the state, finally lead to Brazil‘s bleakly grotesque, grim conclusion, in which there are only two alternatives to conformity, two ways of escaping the system: death or insanity

Verdict: Brazil isn’t subtle, but it is effective, and it is probably both of these qualities that made me fall in love with the film when I first saw it. For a long time, I would have named it as one of my favourite films, and it definitely played a role in my becoming a film geek – not only because of its story and aesthetic, but also because, like Sam Lowry, it is in love with cinema. When I’d last seen the film, however, I found my opinion had somewhat shifted: the positive effect of Gilliam’s self-indulgence, his apparent inability to drop any ideas he’s fallen in love with regardless of whether they serve the whole or not, is that there is a messy richness to his films, but there is a flipside to this: the sprawl of ideas can become tiresome. There is an extent to which I have come to feel that the middle part of Brazil suffers from this – and, not surprisingly, it is also where the supposed love story between Sam Lowry and the object of his fantasies, Jill Layton (Kim Greist, not altogether suited to the film’s style and not always served well by the director) come to the fore. The script of Brazil resists painting this relationship as a romance just enough to make it sort of work (except for the last few scenes with Jill, which warrant a cringe or two), but both the middle stretch of the film in which Sam and Jill finally meet for good is arguably its weakest part, and the one where the length of Brazil most makes itself be felt.

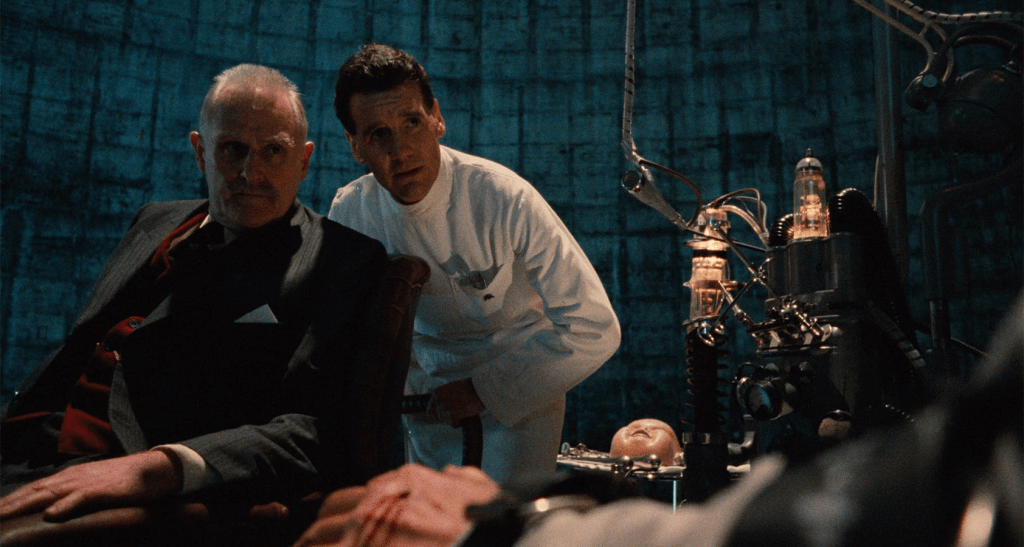

Rewatching the film, though, I found that the visually and verbally virtuoso establishing of the world and characters in the first half, and the final descent into the nightmarish flipside of Sam’s fantasies, the funhouse mirror of the world he inhabits, still make the film deservedly a classic, if perhaps a flawed one. It remains the film by Terry Gilliam that stays with me most, and many of its characters and scenes are indelible: Jonathan’s Pryce doomed dreamer, Ian Holm’s pathetic Mr. Kurtzmann, and perhaps the best ever use of Michael Palin as cheery state torturer Jack Lint; Sheila Reid as Archibald Buttle’s widow, and her haunting refrain of “What have you done with his body?”; the ridiculous, yet oddly inspirational Harry Tuttle (Robert De Niro), the most heroic freelance heating engineer imaginable. And while Gilliam’s boundless inventiveness can become a self-indulgence that causes the film to drag in parts, it is also one of its greatest strengths when it serves the material well. Luckily, this is true for most of Brazil: this is a world that is richly imagined, which makes the film into more than just a satirical take on the excesses of bureaucracy and capitalism. It makes this world look and feel real even at its most grotesque and cartoonish.

What I did ask myself, rewatching the film in 2026: is Brazil‘s dystopic satire still relevant? The fascism of the present day doesn’t use bureaucracy as a Trojan horse: it isn’t cruel by accident and neglect so much as by design. The authoritarians of the present don’t need to disguise their hunger for power with a flurry of forms and processes. Sure, Jack Lint, the film’s blandly cheery face of evil, is still chilling – but the present-day face of evil no longer even feels the need to put on a blandly cheerful mask. And this is perhaps Brazil‘s greatest sadness: watching it now makes its dystopia feel almost cosy at times.