Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

So, apparently Alfred Hitchcock wasn’t a huge fan of Ivor Novello? One wonders what Novello thought of Hitchcock. It’s not exactly a secret that Hitch wasn’t always the easiest director to work with. He famously said that all actors should be treated like cattle, and when he said that he was correcting an allegation that he’d supposedly said that actors are cattle. Arguably, his correction didn’t exactly do much to make him look any better. Of course, being treated like cattle might still have been the better deal compared to other ways in which Hitchcock behaved towards his actors – and particularly his actresses. (It’s no accident that one of the sections in the Wikipedia entry on Tippi Hedren’s is titled “Allegations of sexual harrassment”.)

Alfred Hitchcock wasn’t the only director with a reputation for behaving badly towards his actors. While it’s likely that David O. Russell, director of Silver Linings Playbook, at least got along moderately well with that film’s star Jennifer Lawrence, George Clooney called his work with the director on Three Kings “the worst experience of my life”, and the two almost came to blows. Amy Adams, not exactly someone famous for being hard to get along with, clashed with Russell while making American Hustle to such an extent that Christian Bale (an actor who hasn’t always been perfectly well-behaved either) felt he had to intervene, and she said later that she had no intention of working with him again. Russell even screamed at Lily Tomlin while the two were working on I Heart Huckabees, though she proved more forgiving than Adams.

And it’s not always the directors who are likely to be at fault due to their behaviour: sometimes it’s the actors, or at the very least it’s mutual. Let’s face it: it’s likely that no one much enjoyed working with Klaus Kinski, but not everyone felt they had to draw a gun at the madman of German cinema, which is what Werner Herzog did… and based on the kind of tantrums Kinski apparently threw during the shoot of Aguirre: The Wrath of God, I imagine that some people cheered at least on the inside when Herzog got out his gun.

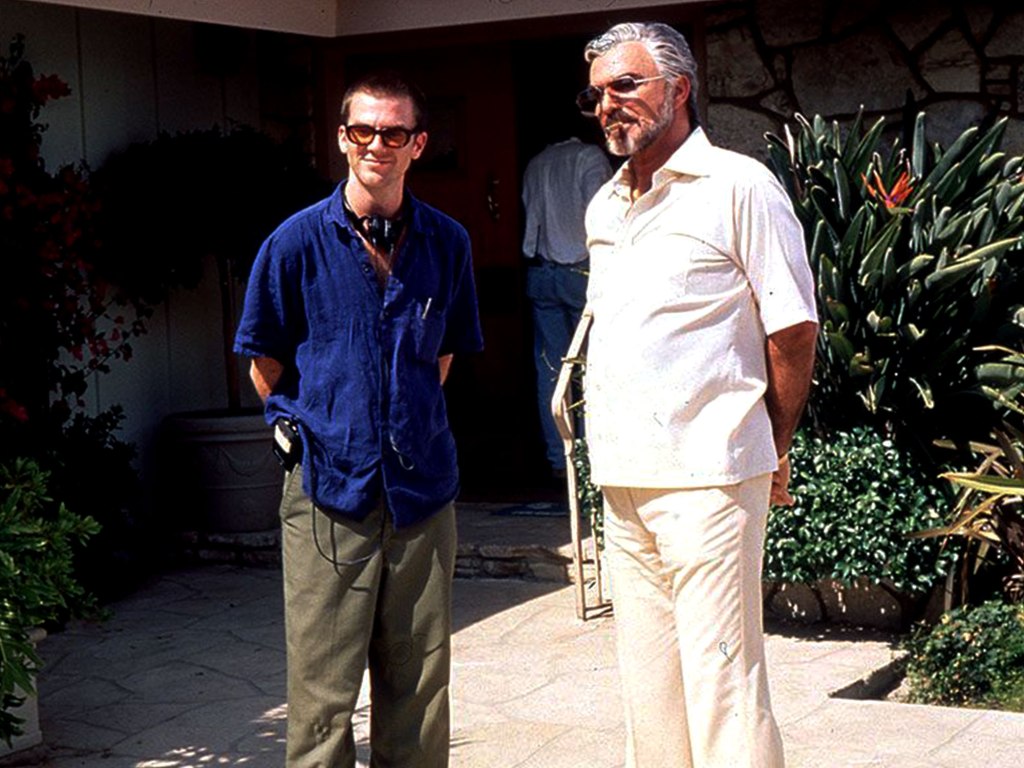

Not every disagreement between directors and actors needs to be this extreme, mind you. Apparently Burt Reynolds didn’t much get along with Paul Thomas Anderson when they worked on Boogie Nights together, with Reynolds feeling that Anderson was too full of himself – which may well be true: artists of any stripe have rarely been known to be without an ego. And there’s a huge difference between having an ego, or frankly (warning, some entirely called-for vulgarity coming in!) even being something of an asshat, and being downright abusive.

It makes me wonder, though: to what extent do artistic collaborations benefit from, or even depend on, getting along? Burt Reynolds may not have come away from working on Boogie Nights a huge fan of Anderson, but their collaboration produced great work, with Reynolds being nominated for Best Supporting Actor at the 1997 Academy Awards. (I’ve not seen Good Will Hunting and don’t know whether he was better than Robin Williams, but as a huge fan of Jackie Brown I’d say that Reynolds’ performance is almost up there with Robert Forster’s wonderful turn as Max Cherry, one of my favourite performances in all of Quentin Tarantino’s films.) In fact, several of the performances I’ve mentioned up to this point were memorable and an asset to the films they appeared in – though obviously, no good performance could ever excuse abusive behaviour between collaborators.

What’s the flip side of this? Actors and directors who are best friends? Who may even be lovers? There are plenty of examples of the latter to be found across film history: Warren Beatty and Diane Keaton, Frances McDormand and Joel Coen, Emma Thompson and Kenneth Branagh, Tim Robbins and Susan Sarandon, Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig. Obviously there’s always a question of favouritism or nepotism in the room when the director’s casts someone who happens to be their significant other, but examples like those mentioned above suggest that it may also be the other way around in some cases: that these artists were attracted to one another because of their creativity and talent.

In the end, there are too many examples of either kind of creative partnership to allow for any generalisations: sometimes the tension of a difficult relationship between an actor and a director can add a certain energy to the resulting performance, sometimes it can just turn the whole thing into a miserable experience that doesn’t even produce a film that both can be proud of as a mitigating circumstance. Sometimes the romantic sparks between collaborators kindle a fire that heats up a film, sometimes that film fizzles out like a damp squib, regardless of how the director and actor feel about one another. Probably all these musings about perfect fiendships and collaborations that are as creative as they are romantic are little more than cinema gossip trying to dress itself up as some kind of grand concept.

But hey, this is cinema, and I’d be lying if I didn’t also enjoy the gossip at least a little. Because, yes, we watch characters on screen, but we also watch the actors portraying these characters. There’s nothing wrong with a little curiosity about what happened when the cameras stopped rolling, the lights were switched off, and the masks came off.

2 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #155: Best fiends and purely professional relationships”