Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness

The power of a Roald Dahl book, when you get your hands on one as a kid, is the undercurrent of danger. Not just the overt peril as described in the books, such as a little girl getting trapped amidst man-eating giants. But also an undercurrent of danger, such as bullying, abusive or absent parents, the overall problem of power and who gets to have it. There is a clear divide between good and evil, and mostly evil is everywhere, above and below the surface. The bullies often have all the power and wield it for their own selfish ends, or without any reason at all. The good, often children, ultimately defeat evil, although this does not necessarily mean that order is restored in the world. It is a world which is frequently unfair, and a great deal of effort has to be expended to try and tip the scales just a little bit in favour of equity.

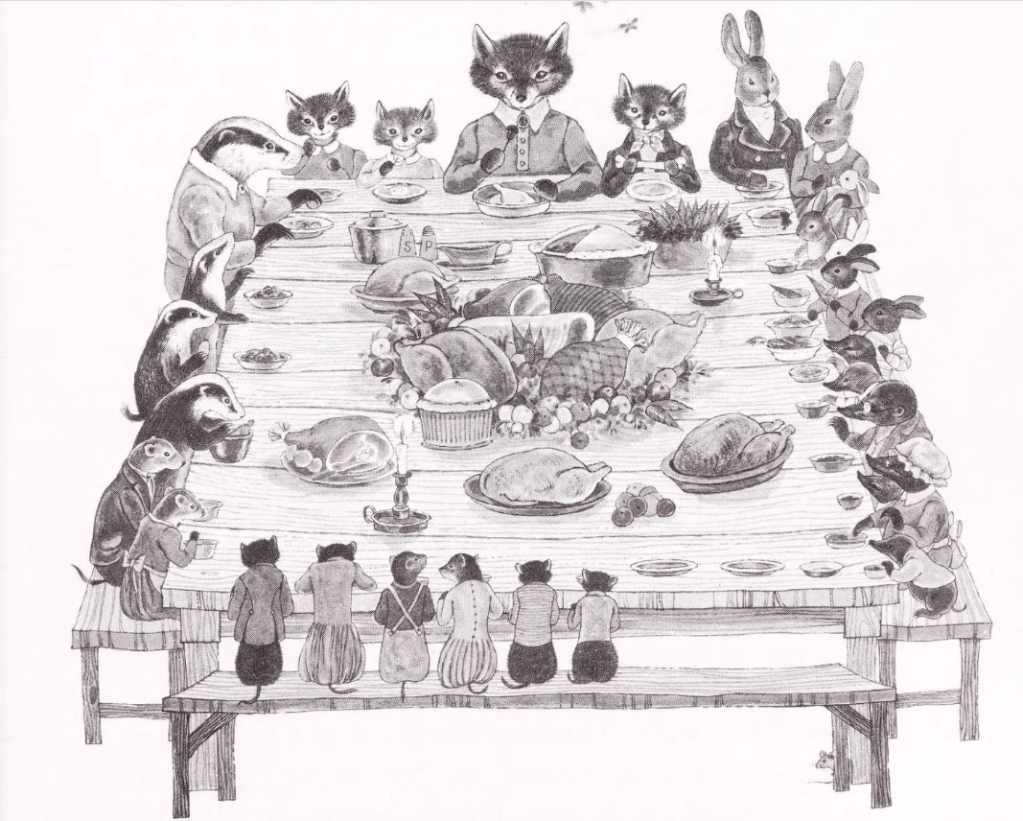

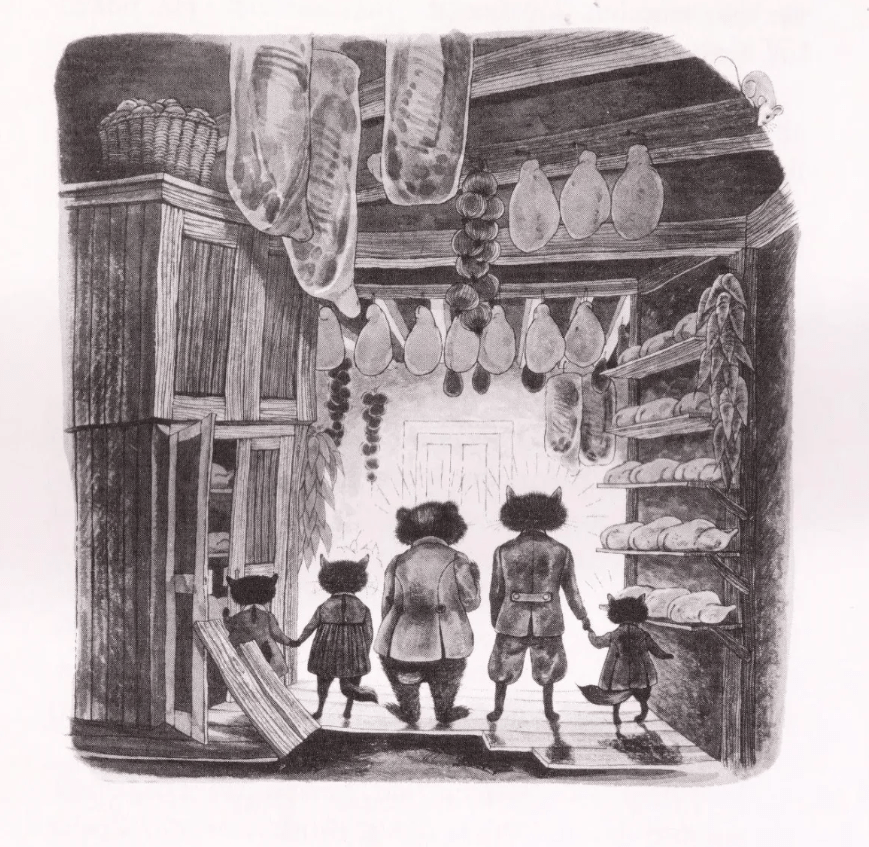

In the 1970 book Fantastic Mr. Fox, three mean farmers wage an unyielding vendetta against a fox, who constantly outsmarts them and steals their chickens. They want to dig up his burrow, and they use heavy machinery to try and do so. The Fox family are not the only ones to suffer from the vengeful farmers: so do all the other animals who live underground. Shut off from their routes to forage, the animals all face starvation, but Fox comes up with an idea. They will create a new underground village to live in, and Fox, aided by a tunnelling system, will be able to forage for them. The farmers, at the end of the book, are left beside the hole they have dug, guns on their laps, waiting for Fox to come out. “And, so far as I know, they are still waiting,” the book ends.

This particular book was filmed in 2009, becoming my very favourite of all the Dahl films. Matt has already written a piece about the magic of stop-motion, and Mr. Fox is a unique example of the technique. The foxes are so tactile with their fur and little outfits, it feels like being led into a miniature animal world that you can almost touch and smell. The film makes me feel like I’m just watching the Foxes and their friends go about their lives. They’re not telling a story for me, they just go about their business and the audience is simply a fly on the wall of the action.

Wes Anderson, instead of overemphasising the plot, also focuses on the Fox family dynamics. In which the Fox’s son Ash (Jason Schwartzman) has trouble adjusting, when a cousin, Kristofferson (Eric Chase Anderson), is introduced into the family. Kristofferson seems almost too perfect, and the question arises, in Ash’s mind, whether the family don’t prefer Kristofferson over him. The plot itself is basically the same. Three nasty farmers need outwitting, and so the movie takes on characteristics of a heist film, as Fox (George Clooney) proceeds to, ahem, relieve them of their fowl. Mr Fox, you see, is no angel. He used to be a chicken thief and bootlegger before he went into journalism, and he misses the excitement greatly. But he’s a family man now and tries to live the straight life as best he can. Until, that is, he again slips back into dining out on stolen chicken. And so, just like in the book, the farmers vow their merciless revenge.

Anderson is a great fit for this material. He has a knack for the slightly odd, but also a very keen eye for his character’s idiosyncrasies. Unlike Matt, I adored The Royal Tenenbaums for the way Anderson dealt with dysfunction. With an absurdist’s eye, he finds both the glamour and the very real tragedy of these broken people, and allows them to shine with all their eccentricities intact. As, in a rather more gentle way, he manages to do with the Foxes. Easy moralizing bromides about life do not apply. A Fox is a fox, and will not change his wily ways. Neither does the film talk down to children, a fact which I would surely have appreciated as a little girl, then inundated with books and films which none too subtly told you not just how to behave, but what you ought to be and aspire to. And, incidentally, what the woman you ought to turn into should look like and aspire to. But this film, like the book, does not shy away from the fact that people – and foxes – are complicated. Not saints perpetually turning the other cheek, but beings who want some restore some justice, some equilibrium in a world in which power rests with the few, and they seldom wield it with evenhandedness in mind.

Dahl’s books have obviously never left me. But I’ve often been critical of the films made from them. Either they add too much sugar, it feels too inevitable that justice is restored in the end, or it is restored too completely. In Dahl’s books, it almost never is. This is a truth too often omitted from works of children’s fiction – or even fiction for adults, for that matter: a great deal of effort can be expended to restore some sort of parity, and the best result one can usually hope for is to weigh the scales just a little bit in favour of the disenfranchised. And accomplishing this is really quite the victory, all things considered.

2 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #163: Fantastic Mr. Fox”