One of the things that video games can do magnificently is create worlds. These posts are an occasional exploration of games that I love because of where they take me.

Still Wakes the Deep is a recent horror game made by the developer The Chinese Room, who had previously released two games I’ve written about, Dear Esther and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (the latter of which I wrote an entry in this series about). While the staff turnover at The Chinese Room has resulted in a company that looks very different from the one that made these earlier games, Still Wakes the Deep nonetheless carries the DNA of earlier titles by the developer; perhaps many of the people working at The Chinese Room these days were inspired by the likes of Dear Esther and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture to apply at the company.

Like these earlier games, Still Wakes the Deep puts the player in a place that is imagined and recreated with a great sense for detail and specificity. Dear Esther was the most low-tech of these, but it still evoked a very particular place that the player explored, much like a virtual site-specific theatre the size of a small Hebridean island. Then came Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture with its technically more advanced Shropshire village, its meadows and fields and pubs and countryside houses. Neither of these two games offered much more in terms of gameplay than “walk around, explore the place, find triggers for audio files and animations that tell you about what happened”. Some might even say they weren’t games at all – a conversation I don’t find particularly interesting, at least when used to beat these titles with a stick. They offered experiences that were limited in their interactivity, but their aim was to tell, and structure, stories in unconventional ways rather than player agency. They were unapologetic ‘walking simulators’, a term often used mockingly by self-proclaimed capital-G ‘Gamers’, and this is what they succeeded at: they put you in a specific place, and in the case of Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture at a specific time, and they used the specificity for storytelling purposes. Even if you’re restricted in what you can do (other than walking around), you felt you were there.

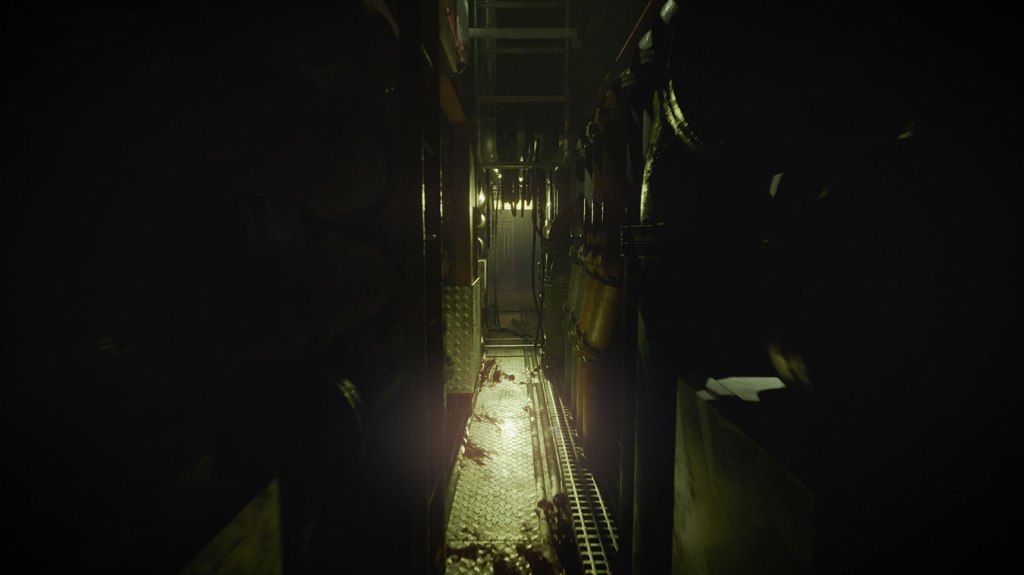

The oil rig of Still Wakes the Deep tops all of The Chinese Room’s earlier titles in terms of the aesthetic realism of the environment it places you in. Using one of the most advanced video game engines available in 2024, the game puts you on a North sea oil rig in 1975, during a disaster that leans heavily into the uncanny and horrific – but even before things go bad, this isn’t a nice place to be. The sea is rough, there’s constant rain and wind, and one of the first things you see in glorious modern graphics is the raindrops streaked across the port holes of the rig. It’s amazing what modern video game engines can do in terms of lighting and fluids and surfaces, and the Beira D oil rig looks and feels real and tactile: the humidity, the dirt, the horrible late ’70s carpets. Add to this the physics simulation, for instance of tarps and tackle in the heavy wind, and the fantastic audio work that The Chinese Room has done, and it’s easy to say that Still Wakes the Deep really makes you feel that you’re on that damn oil rig.

For the first half hour or so of the game, it feels very much like the earlier titles by The Chinese Room – with one exception: both Dear Esther and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture put you in places where you were utterly alone. The Beira D, on the other hand, is filled with everyone else working the rig, and the game deftly combines the graphic abilities of the engine and strong voice work to sketch out the cast of characters.

Then come interactions that, while relatively modest, still make Still Wakes the Deep feel more like a game in the traditional sense: you interact with the world, you push buttons, you replace fuses, you ride elevators and climb ladders. It’s not exactly the high water mark for video-game interactivity, but the presence of non-player characters and more interactivity gave me the impression that The Chinese Room was trying to combine the strengths of their earlier incarnation, the look and feel and specificity of the setting and location, with the possibilities of more involved gameplay.

The problem is this, though: a place can look very real in a game, especially on modern game engines, but it’s in no small part what you’re able to do in those spaces that makes them feel real. The ‘walking simulators’ of yore didn’t let you do much more than walk around – but traversal is a large part of what makes me feel connected to a place. Even if it’s just small choices such as whether to explore this house first or that one, whether to check out the first floor or the backyard: these are what give me the sense that I am in an actual place. Still Wakes the Deep starts out like that, but as soon as the plot is properly set into motion, the Beira D turns into a wet, cold ’70s-themed ride. Where you start off checking out the cramped cabins of your fellow crewmates (again, offering a small but key degree of player agency), you’re now walking down cramped corridors. Doors are locked unless you need to go through them, stairs are blocked except when they get you to the next location – and all of this is amplified by a plot that tells you, “You need to go there now! If you don’t push this button or pull that lever, everyone’s gonna die!” Not that the urgency feels all that real, but the game very much indicates that it doesn’t want you to explore, it doesn’t want you to make this space your own.

More than that, the way the game corrals the player down the right corridors and into the right compartments of the oil rig is almost comically scripted: over the few hours that you’ll spend playing Still Wakes the Deep, you’ll find that walkways are smashed, ladders are broken, gangways are flooded – all of which makes sense with the disaster that’s unfolding, added to which it’s put on the screen with great visual and acoustic fidelity, but somehow it’s always the right ladder that brakes, the right corridor that is flooded, and the right porthole that’s smashed open, so that the main character always ends up exactly where he has to. Need to deactivate some engine because otherwise the spilling oil will ignite and roast you alive? The debris will channel you exactly towards the big button labelled “Deactivate engine”.

It’s ironic: Still Wakes the Deep offers more traditionally game-like interactivity than The Chinese Room’s earlier ‘walking sims’, but for me it loses the strengths of those earlier, more limited games. More interactivity doesn’t mean more freedom, and it’s the lack of freedom – and the obvious way in which it results from plot needs – that undermine the believability of the place established in the first half hour. The player is allowed to do more, but they are entirely at the mercy of the story and its various plot beats – to such an extent that I ended up feeling I was watching a film on a video player that instead of having a button called PLAY and one called PAUSE had buttons labelled “Jump” or “Climb” or “Pull lever”. The game puts me in an environment that looks and sounds real and that is filled with loving, specific detail – but it’s all as on-rails as an amusement ride.

To be fair: Still Wakes the Deep is a good, effective ride. Its setting is interesting, its story well told (if somewhat generic, once you get past the relatively novel setting). But I almost think I would have got more out of being let loose on the Beira D before everything goes haywire and allowed to walk around, listen in on the crew conversations, have a look at the pictures and cards that the crew members had tacked up in their cabins and the books they’d brought to the oil rig. The Chinese Room’s latest is a beautiful, thrilling, well-made ride – but the way that its surface-level realism is undermined by the game it is designed to be and the story it sets out to tell? It made me wish it was a walking sim instead.

One thought on “They create worlds: Still Wakes the Deep and the limits of realism”