Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

Like Sam, I was a big fan of The Little Vampire as a kid – though, unlike him, I was a Book Firster. I loved the books by Angela Sommer-Bodenburg (at least as far as I read them, stopping somewhere around the fourth or fifth volume), and I think I may have had something of a kid crush on the vampire girl the main character fell in love with, but I couldn’t abide what I saw of the TV series. I’d been looking forward to watching the adaptation, but to me at the age of 10 or 11 it felt deeply silly. To be fair to the series, though, perhaps it was simply that I was growing out of the books at the time, and maybe I minded what I saw as the series’ silliness because it highlighted to me the ways in which The Little Vampire was, first and foremost, a series of children’s books. Not YA, not “for all ages”, but kids’ books. Which doesn’t mean that you’re magically too old for such fare at the age of 10, nor that such books cannot be enjoyable as you get older – but, for me, The Little Vampire stopped being as enjoyable as it had been originally. And, having loved the books dearly until then, perhaps that’s why I pretty much stopped reading them from one day to the next.

I was still a voracious reader, though – and, if anything, my hunger for books just grew and grew. I was a regular guest at our village library, driving the librarians barmy with my constant requests for them to let me borrow more books than was permitted. And I quickly started going beyond what was considered age-appropriate reading. I remember ransacking my parents’ bookshelves, reading their German translation of Alex Haley’s Roots around that time, and I read Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose at the age of 12, after seeing the film at the cinema. (Here my Book First tendencies didn’t take, probably because I saw the movie first, and I still enjoy the adaptation starring Sean Connery in one of his best roles much more than the Eco novel.)

Which isn’t to say that I didn’t also read books that were more traditionally considered to be children’s literature. It took a while before the librarians gave up and let me borrow books from the adults’ section, so I read my way through any and all books in the children’s section that looked like fantasy, science fiction or horror. (And, Switzerland being a lot like Germany in that respect, there was a tendency to automatically consider stories in especially the first two of these genres to be childlike fare, so there was a lot for me to read.) Throughout my childhood years, I must have read hundreds of books – especially since I wasn’t a particularly extroverted kid and always enjoyed being alone more, reading and watching TV and playing computer games on my Commodore 64. Like so many readers, I remember whole nights when I just had to know how this or that story continued, so after going to bed I’d continue reading, often until I had finished the whole book.

What I don’t remember so much is what I read at the time. I have vague memories of a couple of books, but very little that is concrete – except for two books especially that I would consider to be among my favourite novels to this day: Michael Ende’s wonderful duo of Momo (1973) and The Neverending Story (1979, though the first English translation only came out in 1983). In many ways, it is especially The Neverending Story that I’d consider to be responsible for making me a reader – and it is one of a very select number of books that I read when I was young and that I still re-read every couple of years.

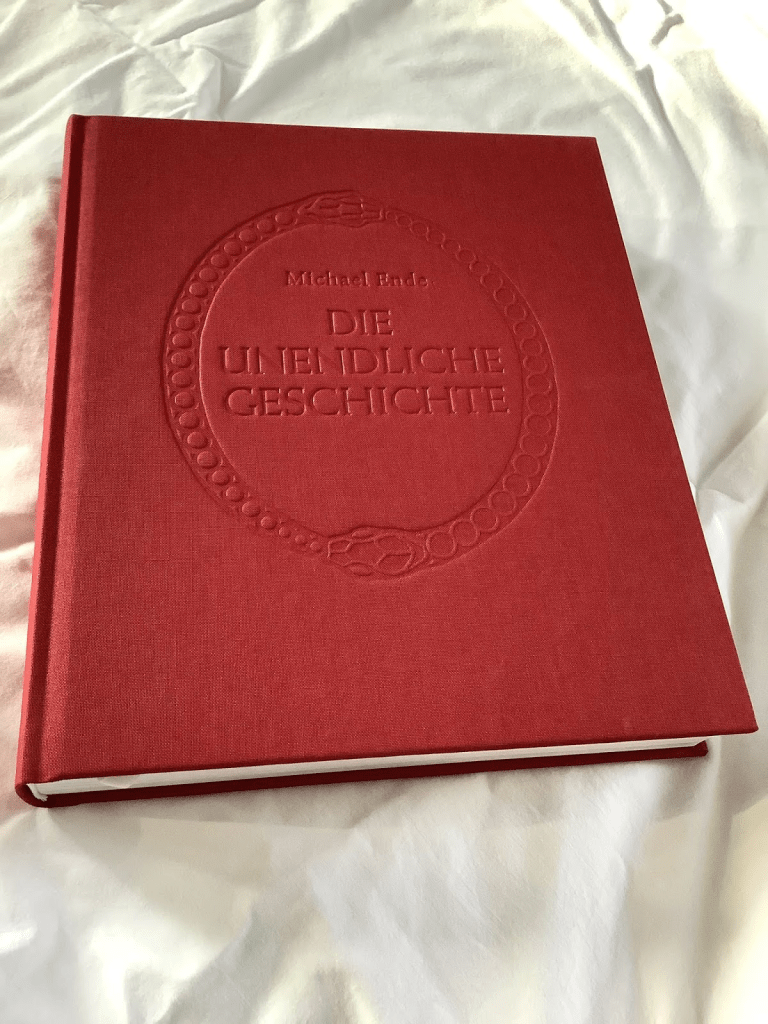

One of the ways in which Michael Ende’s classic fantasy novel stands out for me from pretty much everything else I read during my childhood and teenage years is the book itself: I was lucky enough to get the hardcover edition as a gift from my parents, and this was less a book than it was a volume, bound in what seemed a rich burgundy fabric, with a variation of the Ouroboros embossed on the cover: a circle formed by two snakes, one dark, one light, each biting the others tail. And, on opening the book, I discovered that some of the text was printed in a dark green, the rest in a red not too dissimilar from the colour of the cover of the book. On some pages, the writing might change colour from one sentence to the next, or a single word would be in red when everything before and after was printed in green. What could this mean? Then there were the beautiful initials: The Neverending Story has 26 chapters, the first starting with A, the second with B, the third with C, and so on, and the first letter of each chapter was made into an ornate image, again in the now familiar red and green, showing characters, objects and locations from the chapter to follow. To top it all off, the book had a ribbon bookmark (again in burgundy). This wasn’t just a mass-produced product, it wasn’t just something disposable, to be thrown aside as soon as you’d finished the story: it was a lovingly made, beautiful object. (When my first copy of The Neverending Story fell apart after something like 20 years, I was heartbroken, but I was lucky to find a well-kept version in a second-hand bookshop shortly after. Most modern copies skip the initials or other elements that are so essential to this book.)

Warning: Yes, I will spoil a lot of the story of The Neverending Story, a novel that is over 40 years old by now.

The Neverending Story could have been an utter disappointment if the story itself hadn’t lived up to the intricate object that was the book itself – but it did, and more than that. The colours and the snake emblem and the alphabetical initials, these were more than ornaments or gimmicks, and the book I was holding in my hands was itself a character of sorts in the story. For a fantasy novel, The Neverending Story begins mundanely enough: a boy, Bastian Balthazar Bux, runs from some bullies and escapes into an antiquarian book store, where he finds an odd old bookseller – and also a book, bound in red cloth, with an emblem of two snakes biting each other’s tail, and that book is called The Neverending Story.

Later, when studying English literature at university, I’d find words to describe what Michael Ende was doing in The Neverending Story: metafiction, postmodernism, Chinese box narratives. At the time, I didn’t know any of these terms, but I understood that something special was going on here. Ende inscribed the book I was reading into itself. Bastian steals the book, hides away in his school’s attic and begins to read it, the parts narrating his story were the ones printed in purple, the ones in green were the story set in the land of Fantastica (or Phantásien in the German original) – but the two narratives were permeable, as were the two worlds, entwined in each other like those two snakes. Bastian, the reader, starts to have an effect on the story he is reading as much as vice versa – and if Bastian was reading in a book called The Neverending Story about a magical land, and I was reading about Bastian in a book called The Neverending Story, was there yet another reader reading about me in a book called The Neverending Story? Readers and stories all the way down?

Roughly halfway through the novel, something happens that still blows my mind in its audacity. The Childlike Empress, the dying ruler of Fantastica, takes on the arduous journey to find the elusive Old Man of Wandering Mountain. This recluse is ceaselessly engaged in writing a book – and I’m sure you can guess what this book is called called. The Empress hopes for Bastian, her reader, to save her and Fantastica – as it is only Bastian that can heal her collapsing realm, not by going on a heroic quest or fighting monsters, but by giving her a new name. Bastian, however, is afraid: among other things, he is afraid of the way his own reality is questioned. Is he only as real as the fiction he thought was only reading? As Bastian hesitates, the Empress tries to force his hand. She asks the Old Man to read the book he is writing – which doesn’t just describe the world so much as it writes it into being. He begins to read the story of everything that has happened, in Fantastica, in Bastian’s world – and perhaps also in mine, as I was reading the novel? (Obviously not, but by that point the hold that The Neverending Story had on my imagination was strong enough that I felt, somehow, that I had to be in the Old Man’s book too.) The man retells the entire story up to this point, finally getting to the moment where the Empress asks him to read his book to her. He complies, still, again – and so the story begins again, biting its own tail, confining everyone in an endless loop: the Empress, the Old Man, Bastian, and the person reading Ende’s novel.

Obviously The Neverending Story doesn’t end there (how could it, if it is neverending?), but it is this point in the middle of the story that I find perhaps most unforgettable: the vertiginous vortex of the fiction folding in on itself, threatening to take the characters, their world, and the reader with it. When the film came out in 1984, I had zero interest in going to see it: for one, it looked like it only told half the story, ending a neverending story before it is concluded. For another, it prettified Bastian Balthasar Bux, an overweight, socially awkward kid with no friends, into a cute all-American kid. (I remember conversations at the time among the girls at school who’d seen the film, talking about how cute film Bastian was, and the little book snob that I was rolled his eyes and shook his head at how much this Wolfgang Petersen-directed blockbuster and its fans missed the whole point.)

But most of all, while even as pre-teen me I understood why they might want to make a film of The Neverending Story (as a kid in the ’80s, you quickly understood that money makes the world go round), I always felt that making this story into a film, or a cartoon series, or a computer game, was missing the point. The Neverending Story is a book about a book (about a book, about a book etcetera, etcetera). Gut its metafictional element and you take out what the story is about. Bastian, reading the book he’s stolen, has to make the reader ask themselves whether they are just a character in a bigger story, because they are essentially doing the same as Bastian. You can’t just make this into a film by turning the story into pretty pictures on a screen – or if you do, you’re turning an intricate Chinese box into a badly-made cardboard box ordered on Wish. (If you’re lucky, there is a smaller badly made box inside the first box, but that’s it.) Take out the red and green lettering, the snake emblem, everything that defines the book as an object, and you cut the connection – or at least you exchange it for a much more common form of connection: oh, look at the poor, bullied boy. Look at the horsey and the sad turtle. Look at the furry, flying doggie-looking… that’s supposed to be a dragon?

Even 40 (!) years later, I find it difficult not to take the film version of The Neverending Story personally – much more so than the mediocre TV series they made out of The Little Vampire. I can accept that Petersen’s film adaptation means something to a lot of people, and I can imagine that, if you accept the movie for what it is and what it tries to do rather than measuring it against your favourite book, the adaptation may be a good yarn. But this neverending story isn’t my neverending story – beginning and ending with the book that it isn’t and can never be.

3 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #211: The book’s the thing”