Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

I’ve always been a sucker for stories where protagonists wander through a virtual landscape of their mind: They may think it’s real (or not), but the things they see and the people they meet represent what’s going on in their psyche, the villains they fight are their inner demons, and so forth. They end up working through their shit by interacting with it physically. It’s marvellous!

It’s a narrative that gets explored very often in Western media, and in very disparate genres. In Chinese media, this plays out very differently, as I’ll go into below.

But first a few examples of what I’m talking about!

When Bastian Balthasar Bux, the boy in The Neverending Story, saves Fantastica (Fantasia in the deplorable movie), his story has just begun. After using and abusing his power in Fantastica to create things, he begins to forget. He makes himself strong and forgets he’s ever been weak. He forgets who he is and gets angry at the people who remind him. He loses his own name. Eventually, destitute, he goes down into the Mine of Dream Pictures to search in the dark for a single image of his own father, so he can return home.

Yes, very subtle. But I ate it up as child and it still gives me the shivers 40 years later.

You’ll find the idea of a mental landscape a lot in animated movies like Puss in Boots: The Last Wish and, of course, Inside Out.

A very different example is the 2018 Netflix Miniseries Maniac, with a narcissist Emma Stone and a lost-looking Jonah Hill as two social outsiders who take part in a clinical trial. The medical treatment that is supposed to supplant therapy puts patients into virtual scenarios in which they reenact the conflicts going on in their minds. The virtual scenarios are very genre: a 1920s detective setting, for instance, a Tolkien setting (with Emma Stone as a permanently drunk half-breed Ranger), an alien invasion. The whole thing is framed by a retrofuturist, absurdist reality. It’s a glorious, generous, quirky and subversive series. Subversive in a very American way: things get resolved at the end, but boy, do they get resolved by chaos goblins! No socially appropriate endings and soothed emotions for you, suckers!

I’ve never seen anything like it in a Chinese series. If you know me, you know I spend most of my media time watching Chinese series. I’m by no means an expert, just a fascinated watcher of cultural differences.

And Chinese cultural expectations do not lend themselves well to the exploration of the psyche. In fact, one of the most frequent things you’ll hear in a Chinese series (apart from “come eat”) is “don’t overthink it” when a character falls into rumination. If a character starts crying, another will tell them to “quickly stop crying”. This is meant lovingly and is supposed to help you take heart and get back on your feet.

That’s not to say that Chinese characters are psychologically simple. Quite the opposite. On the whole, Chinese directors trust their audiences to understand why people act the way they do. Characters may work through their complex feelings for one another without explaining themselves, how close people stand to each other (or not) conveys volumes of meaning, the looks they throw may be bland but if you understand the context you’ll understand how loaded they are. (In The Geography of Thought Richard E. Nesbitt talks about how Chinese and Japanese children are taught as toddlers to identify feelings and context – “the fish is sad because the other fish pushed past it” – while Western children are taught to identify objects – “that’s right, it’s a car! What colour is the car?” And doesn’t that make us sound like budding psychopaths.)

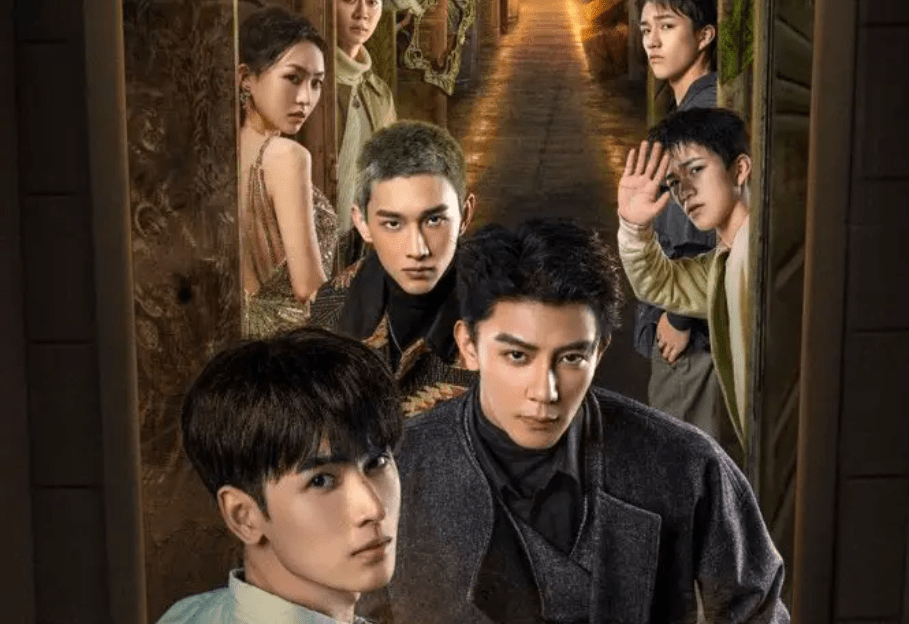

So when I started watching a Chinese series called The Spirealm on the strength of its description, I expected nothing more than a story about a guy in a personal slump who gets trapped in a deadly video game. “Ling Jiu Shi finds himself inexplicably thrust inside a mind-bending reality dictated by an enigmatic Virtual Reality game where he must pass twelve doors to escape. The catch? Each door initiates new mysteries to solve and conditions to abide by.” The “taboo conditions” mentioned here, like “don’t leave your room after 8pm”, are fatal.

So you’re going about your day and a door appears. Behind each of the doors lurks a fantastical setting with a vengeful spirit (a well-worn trope in Asian movies) that kills you if you don’t solve the puzzle. I can’t stress enough how amazing and lovingly fleshed out the settings are. In each of the door realms, you’re competing against or working together with a different set of players, also trapped in there. After you successfully complete a door, you get to walk back out and be safe for a while. Until the next door appears in front of you.

Right in his very first door, Ling Jiu Shi, nicknamed “Ling Ling”, finds an ally in the experienced player Ruan Lan Zhu. Lan Zhu runs a pro group called Obsidian that accompanies people for money to help them pass their first four doors. The ally soon becomes a friend and the two glom onto each other in this very intense “I will spend a lifetime keeping you safe and naturally we’ll share a bed because we’re such good friends” kind of way you see a lot on Chinese television ever since China banned depictions of gay people on screen in 2016. (This did not help, as The Spirealm apparently got yanked off air in China only two hours into the premiere.)

Ling Ling has a knack for the game, he’s unfazed by the vengeful door ghosts. His inclination is not to defeat them but to understand them and help them come to peace.

As the game progresses, it becomes obvious that it is not just a game. It has a lot more to do with Ling Ling’s mind than he realises. Artifacts from his childhood appear. At one point he is exploring the rooms in a house and finds his own dorm room from college, complete with his stuff still on the table. NPCs start giving him clues that nobody else gets. Someone has made this game with Ling Ling and his troubled past in mind. And he has no idea why and what that means.

It’s possible to watch this as a series about a game. It’s also possible to see the door ghosts with their grievances and Ling Ling with the tantalising hints about his past, and see some suspicious parallels. The Spirealm is immensely rewatchable, as you’ll be tempted to check whether the conclusions you drew in the final episode 38 really match up with the clues in episode 1.

This is not an American series. It’s not blatantly colourful and absurdist and cynical – it’s mysterious and muddled and full of people and their emotions. And with that, I’ll stop spoiling it because you should really go watch it yourselves.

3 thoughts on “Six Damn Fine Degrees #212: Traipsing around in your virtual brain”