Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

Differently from some of my co-baristas here at A Damn Fine Cup, I don’t have any kids, which means that I can neither share all the books, films and series that I loved as a kid with them nor can they show me their weird and wonderful discoveries in pop culture. Which, in some ways, is perhaps what I would enjoy most about being a parent: telling them about the stories close to my heart and being there to see them discover those stories. Though I guess there’s also the flipside: I’m not sure I would be very happy to find out that a kid of mine read, say, The Neverending Story and didn’t care for it.

These days I’m probably more about film and TV series, in large part because reading takes more time, leisure and especially energy, and those are in short supply next to a more or less full-time job. It’s easier to sit down to watch something after a day at the office has left my brain frazzled. Not that I consider watching something a more passive endeavour: sure, it can be, but engaging with any kind of culture is an activity unless it’s just running as background noise. But starting to read takes more up-front energy than picking an episode and starting to watch that, unless we’re talking about the kind of book that leaves you anxious to find out what happens next.

If there is one thing I miss about being a child, it’s the endless energy and leisure I had for reading. I remember getting a new book that I feel in love with and staying awake until the wee small hours of the morning because I couldn’t imagine going to sleep before finishing it. I remember how much I loved pretty much melting into my ugly brown ’80s bean bag reading book after book after book. I wasn’t always a particularly happy child, but reading always brought me happiness, because it brought me escape.

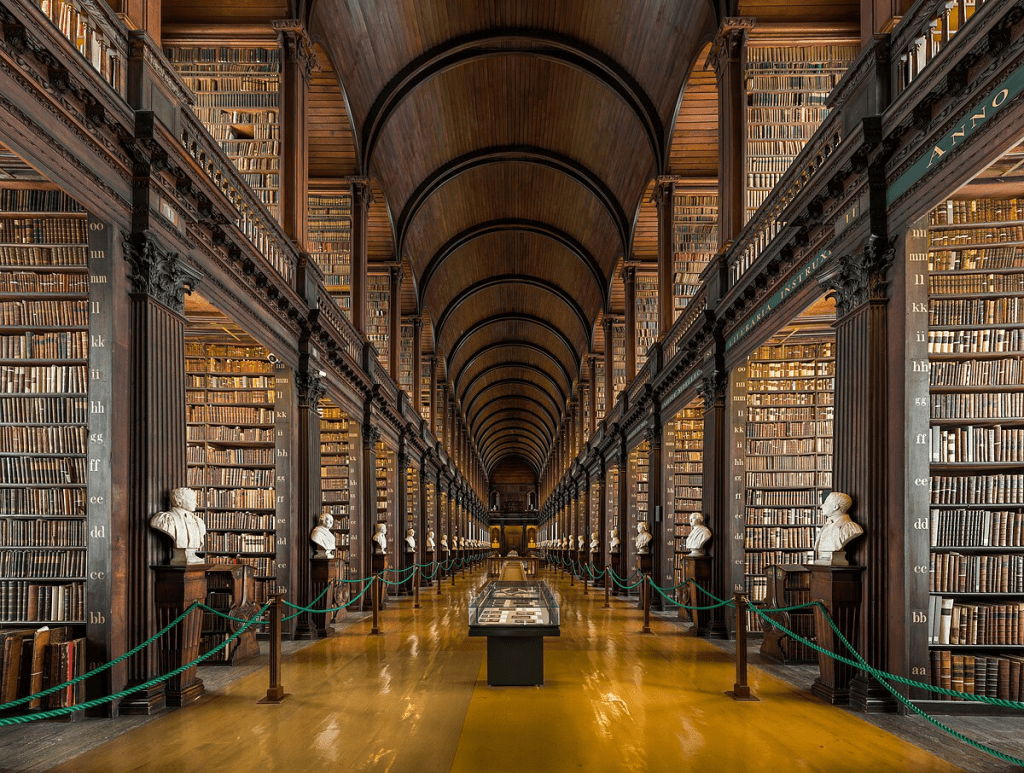

Which is also why the other place that I loved as a child was our local library – which, considering how small and rural a village I grew up in, was surprisingly big and well stocked. I had a fair number of books at home, and I also reread some of those religiously, but in parallel it was the greatest thing to be able to go to the library twice a week, bring back my books and pick up new ones. If I remember correctly, they had a rule: people, or at least kids, could only take out two books per visit, which meant that I could read four library books per week – and most of the time, that’s exactly what I did. I’d always have a backlog of books in mind that I’d come upon previously, so already at the time I started to get used to the idea of ever-growing backlogs of culture that I’d never get to the end of. And the best was getting to the summer holidays – because that’s when everyone’s book-borrowing powers were super-charged and the librarians let us take home not two books per visit but an awesome, wonderful four – i.e. during the summer holidays I would sometimes manage to borrow and read eight books a week, which for a kid who was an introvert, bad at sports and games, and not particularly keen on warm weather, was absolute bliss. Books were my drug, and I was eager to prove that you couldn’t overdose on books.

If there was one thing that I didn’t like about our library, it was this: we had lovely librarians who loved books and loved readers just as much – but they had certain ideas about which books were more worthwhile than others, and those were ideas I didn’t particularly share. They were wonderful in letting me borrow books from the adults’ section at the age of 10 or 11 already (after a bit of discussion, but eventually my obvious seriousness about reading won them over… or perhaps they just had better things to do than argue with a kid about their reading habits and preferences), but they kept nudging me towards the kind of books that were about heftier topics: stories critical of society, political stories, just packaged for a younger audience. Basically the kind of children’s books that you’d imagine Ken Loach to have grown up reading: stories about poverty, struggle and solidarity, stories with parents slaving away in factories or fathers being made redundant.

I didn’t mind the sentiment, but I minded the didacticism of it all, both by the books and by the librarians. Because, for me as a kid, books weren’t about social realism. I loved fantasy and science fiction and ghost stories – and here’s the thing: while a lot of what you get in those genres wasn’t very good, the same is true for the more ‘wholesome’ reading matter. I didn’t have the words for this as a kid, but I had a growing awareness of Sturgeon’s law: “ninety percent of everything is crap.” Of course, I read a lot of that crap, and I enjoyed some of it – but I resented this notion that books with dragons and spaceships were worth less exactly because they were about dragons and spaceships. Because the best of these books were about, well, struggle and solidarity, about sacrifice, about what it means to try to be a good person. But at the same time they were about fantastic worlds, about adventures. In a way, my favourite stories were about putting real toads in imaginary gardens, as Marianne Moore put it so memorably. The notion that something fantastic by definition was only escapism, nothing more than childish fare, seemed to underlie the well-meaning nudges from the librarians. And, most likely, I reacted to this by borrowing the occasional book that was more ‘proper fare’.

Which isn’t bad, I guess. There’s absolutely an argument to be made that reading more broadly made me more aware of how the books I was reading were written, even as a kid. And if one of my four weekly library books was about the ‘real world’, that still meant that the other three were about ghosts or goblins or astronauts or aliens – and, during summer, I could take a holiday from the more supposedly serious reading matter and go for a ratio of one to seven.

But, regardless of what I read and how much I let myself be influenced by the educational nudging of the librarians, I loved the library. I loved this little, perfect world where every book was a portal to a different world and into the head of a different set of characters. And I miss being able to read so voraciously. If there’s one thing I’m hoping I’ll be able to do when I reach retirement age, it’s this: finding a local library – and reading.