Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

Tom Hardy is probably most famous for his hardman roles, Michael “Charles Bronson” Peterson, Britain’s “most violent criminal”, being just one of them. Ask people which of Hardy’s roles they first think of, I’m pretty certain that The Dark Knight Rises‘ Bane will come up, or “Mad” Max Rockatansky (who, admittedly, isn’t half as hardass as that film’s Imperator Furiosa), or perhaps his characters from Peaky Blinders and Taboo. It makes sense: Hardy is nothing if not an imposing figure these days, a far cry from the evil-yet-slender Patrick Stewart clone he played way back in Star Trek: Nemesis (not a recommendation, even for Hardy fans – or Star Trek ones, for that matter).

Frankly, though, as much as I like Hardy when he’s working with good material, he’s not nearly as imposing as the O.G. Tom Hardy: Thomas Hardy, the literary pugilist of English Literature. There’s nothing quite like the world of pain that Hardy can put you in.

I only discovered Thomas Hardy when I started studying English Literature. Before I’d read a lot in English, but few of the authors that might have been considered classic at the time, and much of my reading was genre fiction: sci-fi, fantasy and horror. One of the first things we were introduced to as freshly hatched EngLit students was the “Required Reading List”, a concentrated, boiled-down version of the canon of English and American literature: Shakespeare, Byron, the Brontës, Melville, and some more modern authors, such as Virginia Woolf or Toni Morrison. Thomas Hardy was also on the list, falling in between the older classics and the Modernists.

I don’t remember whether the one novel by Hardy that everyone was supposed to read was Tess of the d’Urbervilles or Jude the Obscure, but either way: I read both, and boy, did Hardy’s relentlessly bleak turn-of-the century world resonate with me. For a number of reasons, at the time I was drawn toward the darker, grimmer corners of literature (and film), and I found plenty of that darkness in Hardy’s novels, in particular those two, the last novels Hardy wrote. But lest my tongue-in-cheek intro gives anyone the wrong impression: Thomas Hardy’s stories were by no means about hard men making hard choices. They were brutal, but their brutality wasn’t that of bruises, blood and broken bones, and Hardy’s prose was nothing if not dominated by empathy for his characters. No, he wrote about the moral and emotional brutality of late Victorian England. His characters struggled, usually in vain, against the social constraints imposed on them, and the way these constraints wormed their way into the characters’ hearts and minds. He dissected society’s conventions to do with sex, marriage, religion and education, and exposed these for what they were: shackles to keep people in place, gears to grind them under, weapons with which to beat them into submission.

Of these characters, it was Jude Fawley, the protagonist of Jude the Obscure (1895), that resonated most with me. The fascinating thing about Jude is that he is not a mere victim of social constraints, he is not simply an object: his tragedy is certainly set on track by the society he is born into, but it is his character, his pride, his obstinacy, that amplifies it. Hardy’s characters have limited choices, but they do have choices – except the social costs of these choices pile up until they eventually become the rope the characters are left to hang themselves with.

There is an aspect to reading Hardy’s later novels that is almost masochistic: it is clear early on both in Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure that any silver linings are temporary at best, and that often they simply light the way from one bad situation to another one that is even worse, exactly because there is the slimmest chance of things getting better. But no: there is an implacable logic to their fates that almost takes on a religious quality – there is a god in the world of Thomas Hardy, and he is a cruel god who knows how to inflict the most suffering, but this suffering does not lead to redemption. As Hardy writes in the last few sentences of Tess of the d’Urbervilles: “‘Justice’ was done, and the President of the Immortals, in Æschylean phrase, had ended his sport with Tess.”

And yet, there is a beauty to Hardy’s stories and his prose. For all of the bleakness of his novels, he feels for his characters, and he prompts his readers to do the same. There is likewise an anger to these works: without veering towards the didactic, Hardy shows that the world wouldn’t need to be as unfeeling and cruel as it is. There is no inherent need for society to be antagonistic. The characters that people his world set in the south of England deserve better. Without this anger and the acute empathy he evokes towards his characters, these novels would be unbearable – and, frankly, even like this, they can be tough to get through.

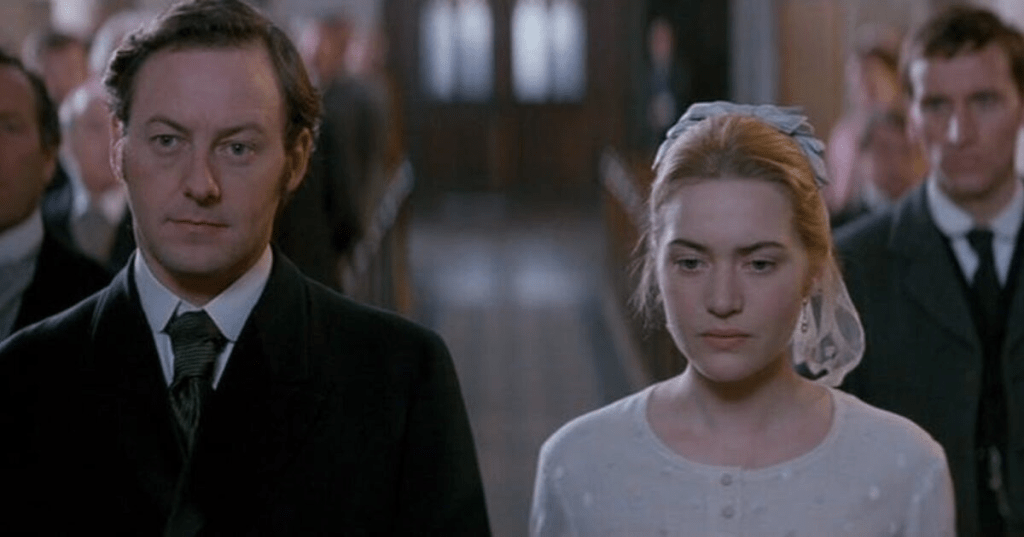

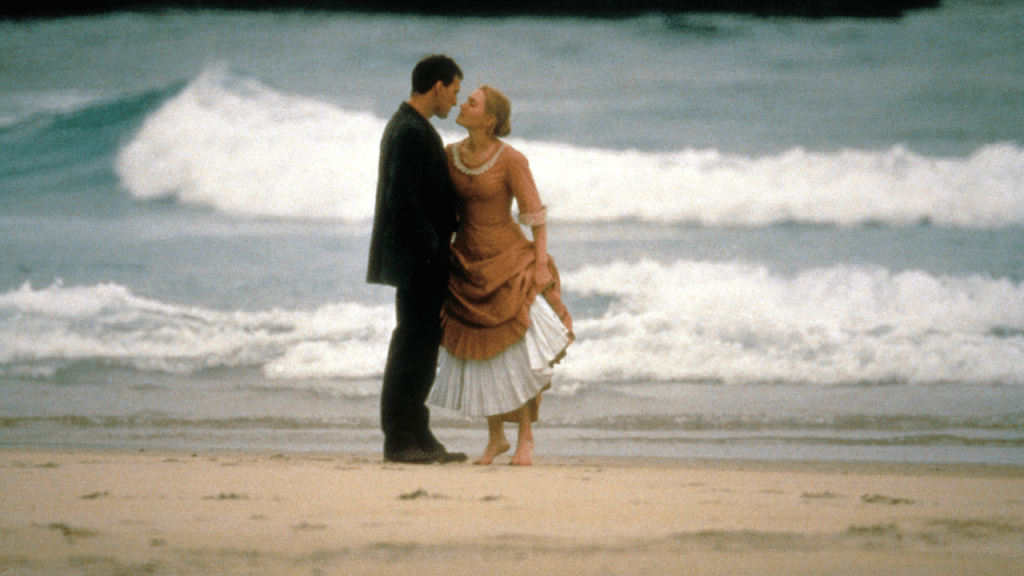

In that respect, it doesn’t come as a surprise that this aspect was often toned down when the novels were turned into films. Jude, the 1996 adaptation of Jude the Obscure directed by Michael Winterbottom, first follows the novel and its plot to a T but then stops short, leaving out its final chapters. No one who hasn’t read the original novel would come out of Winterbottom’s Jude saying that the film pulls its punches: this is a story that goes to dark, dark places. But Hardy gives Jude the Obscure an epilogue that is still among the bleakest, grimmest things I remember ever reading – and it hits all the harder because of its pitch-black, bitter humour. But, picking stills from Jude and from Roman Polanski’s adaptation of Tess, it is striking how much more romantic these stories and their characters look through the camera lens, portrayed by the likes of Christopher Eccleston and Kate Winslet.

Every now and then I feel like revisiting Thomas Hardy. I loved these novels when I first read them, and I reread them repeatedly during my studies – but I’ve not touched them in what must by now be twenty years. When I look for something to read and come across Jude the Obscure on the shelves, I first remember how strongly I felt about the novel at the time, and then I remember how Hardy’s novel finally made me feel. Who knows: perhaps I should choose some of the author’s other novels, to see what else he had to offer than those two magnificent, depressing downers of English literature. Whatever else he puts his characters through in his earlier works, he kept the worst for the end – and it is understandable that, having finished writing Jude the Obscure, Thomas Hardy stopped writing prose altogether.

P.S.: Four years after Jude, Michael Winterbottom adapted another novel by Thomas Hardy: The Mayor of Casterbridge, a novel that, while by no means light reading, is much less grim than Hardy’s two final novels and more in line with other 19th-century tragedies critical of society. Winterbottom’s adaptation, The Claim, is a much looser take on Hardy’s material and one that leans more into a notion of tragedy stemming from character at least as much as society – but there was also less need to tone down the material to make it the slightest bit more palatable.