Welcome to Six Damn Fine Degrees. These instalments will be inspired by the idea of six degrees of separation in the loosest sense. The only rule: it connects – in some way – to the previous instalment. So come join us on our weekly foray into interconnectedness!

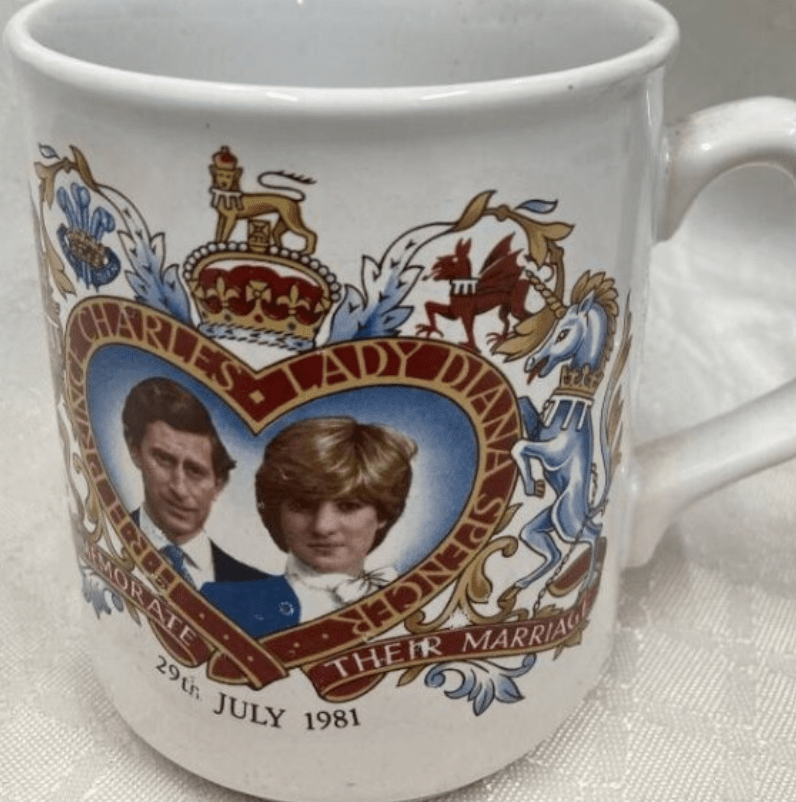

In July 1981, my school went a bit mad. The heir to the British throne Prince Charles was getting married to Diana Spencer, someone the media genuinely referred to “a commoner”. Parts of the UK were getting insanely excited by the prospect, and this included my classroom. The Wedding, we were told, was a Big Event. For kids, this was an event that had everything. After all, there were Princes and Princesses, images of fancy soldiers and decorated palaces, alongside lots of maps smothered with pink. Union flags appeared in the school, and no trip to the shops was complete without seeing aisles of colourful tat with crowns on it.

This school fostered patriotism didn’t stop with the wedding. In early 1982, the UK went to war with Argentina and won – an excuse for even more flags, more maps and the general excitement that the Empire had struck back, ensuring that bits of the map had remained resolutely pink.

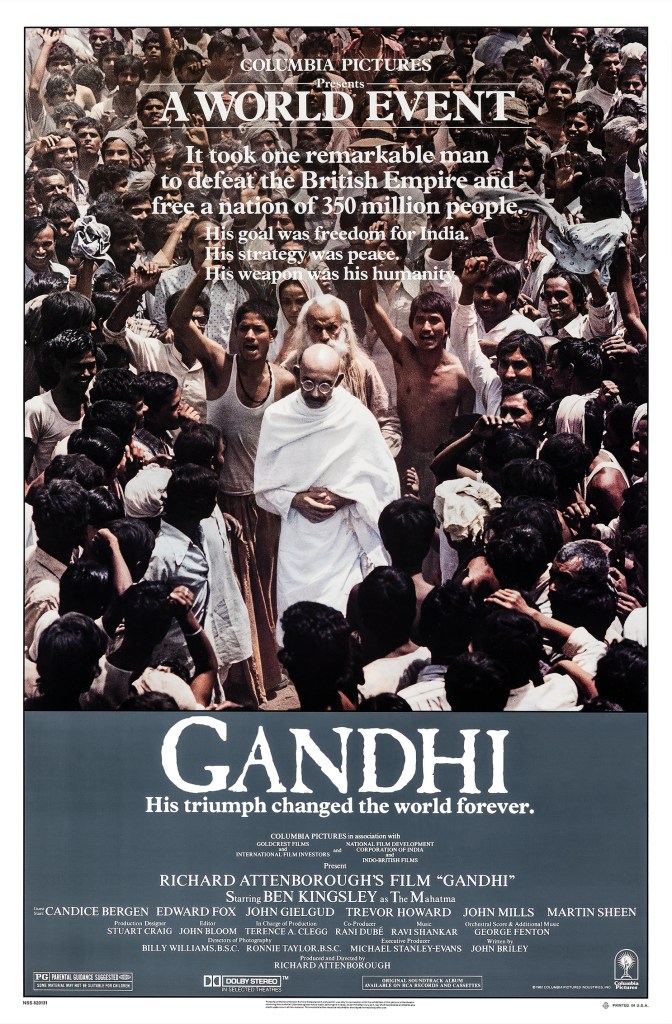

Seven-year-old me lapped all this stuff up. Which must have been slightly galling for my Irish dad. And which is probably one of the reasons why, at the end of the year, he took me to see Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi.

I was reminded of this event when reading Matt’s column last week about watching films and television with his parents, and those memories that linger of the experience.

A strong memory I have of this trip is simply pure excitement. I’m one of four kids, so it really wasn’t often you actually got to do something outside the house with just one parent. And this was going somewhere in the evening, which was clearly “grown-ups’ time”. I have such a vivid memory of feeling like I wasn’t just a small kid going to the cinema that day. Everything felt just more civil. The lack of whining arguments with siblings, the fact I could get a drink and some sweets and – sweet hallelujah – didn’t have to share!

It also felt like a “grown-up” film, which added to my inner feeling of maturity. This wasn’t some animated piece of Disney nonsense that my foolish, youthful self would have gone crazy for a few months earlier when I was just a naïve six-year-old. This was a film all about adults talking, perfectly suited to a seven-year-old sophisticate that I had evidently become.

Giddy with mature excitement, I was swept along when the film started. I’d never seen anything like it before, but there were numerous elements that were comfortably recognisable from all the patriotism I’d enjoyed at school. There were flags, red coats, symbols of the Empire.

It was also full of adults talking, but I don’t remember being bored. I probably didn’t really understand everything that was going on, but the onscreen narrative was doing enough to keep me jolly. Some of these people seemed to be being horrible bullies – but these were ultimately the sensible good guys. I imagine this bullying would be sorted out by the end of the film.

And then the film gets to a pivotal sequence: the Amritsar Massacre. I can still recall the searing, terrible shock of that sequence. I sat there entranced, horrified by what was unfolding on screen. This wasn’t what Good Guys did? What was going on? There was death, and fear. I was overwhelmed by a numbing feeling that something had gone incredibly wrong, and it all seemed so real.

are we the baddies?

I wasn’t thrown out the story, though. I remember being gripped by the rest of it. It has a scale that I don’t think my brain could process quite fully – the journey of the film, over three hours long, far greater than anything I had encountered before. It’s probably overselling the film to say that all human life is here, but for a six-year-old, it probably wasn’t far off being true.

The shock that such a massacre was perpetrated in the name of such recognisable symbols lingered with me for a long time. However, it didn’t inspire any Damascene conversion: I didn’t get on the school desk the next day and scream: “Mr Teacher, Tear Down These Flags!” In fact, I still enjoyed a lot of the junior pomp at school. It’s just that, in one small way, my worldview had been widened. And a few years later, History became a subject at school, and the teaching was generally incredibly nuanced and fair. It’s a myth, I think, that British history is taught in schools as one-sided and jingoistic. The real culprit when it comes to the UK’s insistence on lauding its Empire as somehow a “Good” one is the wider society.

In the decades since, I’ve rewatched the epic a couple of times. I think it still holds up, although its hagiographical tendencies are now slightly jarring. It feels like a British film industry that once celebrated Imperial heroes has swung the pendulum the other way, to laud anti-Imperial heroes with the same underlying idea that displaying the heroism is more important than factual accuracy. Ben Kingsley’s performance is fantastic, and the overall measured celebration of dignity and condemnation of oppression never feel trite. I have to accept that the narrative simplification to create Heroes and Villains in this story creates a misleading, romanticised message – even if I have a lot of time for that message.

So Gandhi remains a film that means a lot to me. Both the memory of the film trip itself, and the time going to the cinema with my father – but, more than anything, the shocking presentation of the crimes of an Empire that society at the time seemed hell-bent on celebrating.